Are the Courts Making It Up As They Go?

The tension between legal principles and political reality in US court system.

Learning Objectives

Understand the concept of judicial review and its origins in American government.

Analyze how judicial appointments and polarization shape the ideological composition of courts.

Identify the structure of the federal court system and how cases navigate through it.

Evaluate the various factors that influence judicial decision-making.

Introduction: The Court as Constitutional Umpire?

When Chief Justice John Roberts sat before the Senate Judiciary Committee during his 2005 confirmation hearings, he described his vision of a judge’s role: "I will remember that it is my job to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat." This metaphor of judges as neutral arbiters who merely "call balls and strikes" (rather than taking an active role in policy-making by “pitching or batting”) reflects an idealized vision of an impartial judiciary that stands above politics and ideology.

Yet this vision contrasts sharply with how the courts—particularly the Supreme Court—are perceived by the public and analyzed by political scientists. Far from being merely technical interpreters of legal texts, judges make consequential decisions that shape American policy and rights in profound ways. From determining the constitutionality of healthcare legislation to establishing or eliminating reproductive rights, from expanding or contracting voting access to defining the boundaries of executive power, the federal judiciary exercises enormous influence over American political life.

This tension between the ideal of impartial justice and the reality of judicial power raises fundamental questions about the proper role of courts in a democratic system. Which cases do judges hear? How do they decide cases? To what extent should judges consider public opinion, and how does polarization affect the legitimacy of judicial decisions? This chapter explores these questions by examining the institutional design of the federal judiciary, the process through which judges are selected, and the various factors that guide judicial decision-making.

Like other aspects of American government, the judiciary has been shaped by path dependence—early institutional choices that continue to influence its structure and operation today. Yet the judiciary has also evolved significantly from its constitutional origins, developing powers and practices that the Framers could not have fully anticipated. Understanding this evolution helps explain both the enduring principles and ongoing controversies in America's judicial system.

Constitutional Design and the Origins of Judicial Power

The Constitutional Framework

The Constitution provides a remarkably brief blueprint for the federal judiciary. Article III states simply that "The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish." This sparse framework left considerable flexibility in determining the judiciary's structure and powers.

The Constitution established basic parameters for judicial independence, stipulating that federal judges "shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour," effectively creating lifetime appointments. It also prohibited the reduction of judges' salaries during their tenure, protecting them from financial coercion by other branches. These provisions aimed to create a judiciary that could make decisions based on law rather than political pressure.

However, the judiciary was also constrained by constitutional design. Unlike Congress and the president, federal judges lack independent enforcement mechanisms for their decisions. They depend on the executive branch to implement their rulings and on public acceptance to maintain legitimacy. As Alexander Hamilton noted in Federalist No. 78, the judiciary has "neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.”

This institutional arrangement created a judiciary that was simultaneously insulated from direct political pressure yet dependent on other political actors for its effectiveness—a delicate balance that continues to characterize judicial power today.

The Emergence of Judicial Review

The Constitution does not explicitly grant federal courts the power to invalidate laws passed by Congress or actions taken by the executive branch. This power, known as judicial review, emerged instead through precedent established in the landmark case Marbury v. Madison (1803).

Marbury v. Madison arose from political conflict between the outgoing Federalist administration of John Adams and the incoming Democratic-Republican administration of Thomas Jefferson. In his final days as president, Adams appointed numerous Federalists to judicial positions, including William Marbury as justice of the peace for the District of Columbia. When Jefferson took office, his Secretary of State James Madison refused to deliver Marbury's commission. Marbury sued directly in the Supreme Court, seeking a writ of mandamus to compel Madison to deliver the commission.

Chief Justice John Marshall, writing for a unanimous Court, held that while Marbury had a right to his commission, the Court lacked jurisdiction to issue the requested writ because Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789—which had authorized such action—impermissibly expanded the Court's original jurisdiction beyond the limits established in Article III of the Constitution. By declaring this portion of the Judiciary Act unconstitutional, Marshall established the Supreme Court's authority to review the constitutionality of legislation, creating a precedent for judicial review that fundamentally shaped the American constitutional system. This principle transformed the judiciary from a relatively modest branch into a crucial check on both congressional and executive power.

Regardless of its origins, judicial review has become a cornerstone of American constitutionalism. It provides a mechanism for enforcing constitutional constraints on majoritarian politics, protecting both the structural features of the Constitution and the rights it guarantees. However, judicial review also creates democratic tensions. When unelected judges invalidate laws enacted by elected representatives, questions arise about democratic legitimacy. This counter-majoritarian difficulty—the challenge of justifying judicial invalidation of democratic decisions—remains a central tension in American constitutional theory and practice.

The Structure and Operation of Federal Courts

The Three-Tiered System

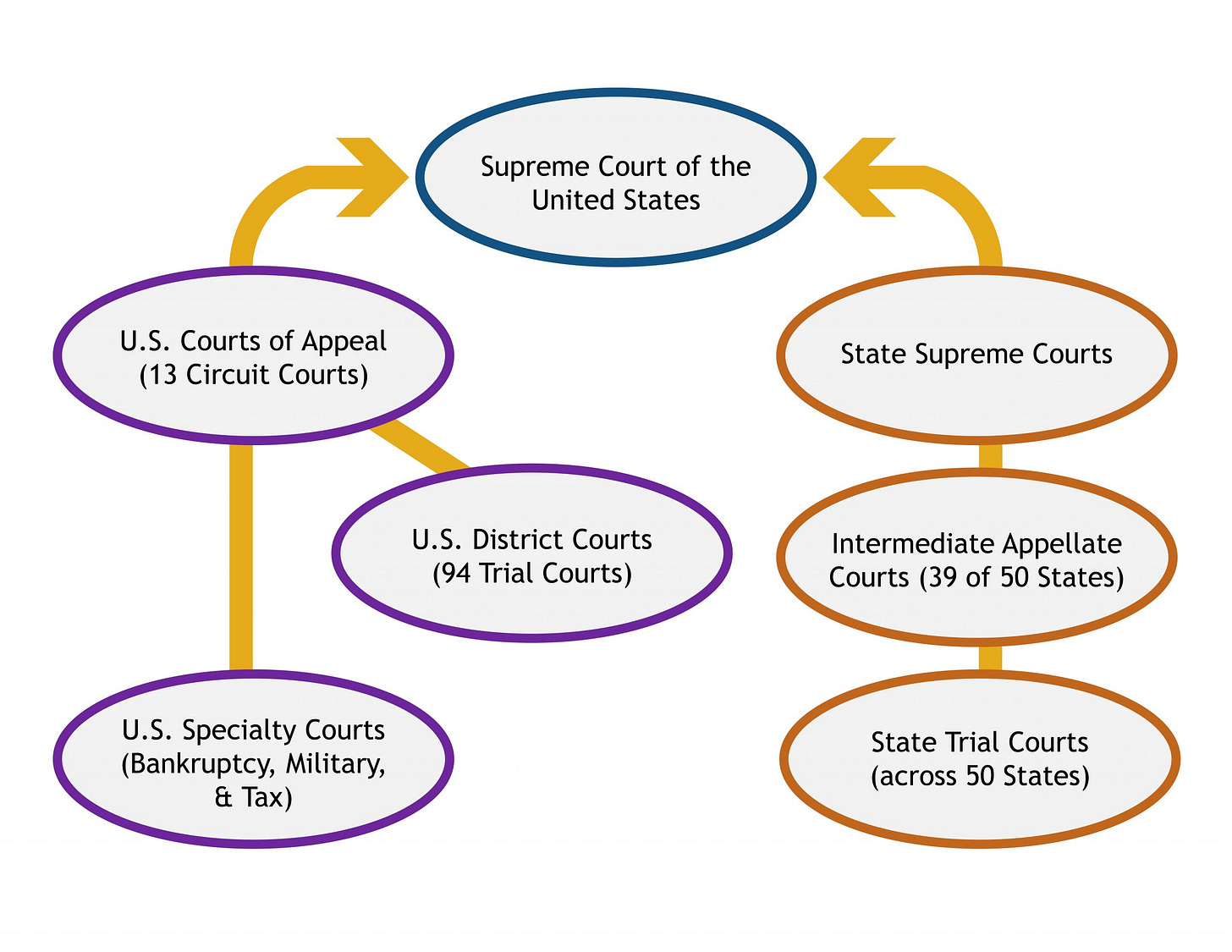

The federal judiciary operates through a hierarchical structure comprised of three main levels:

District Courts: The 94 federal district courts serve as trial courts for the federal system. These courts hear both civil and criminal cases that fall under federal jurisdiction. Each district court is presided over by one or more federal district judges, who oversee trials, rule on motions, and issue decisions. District courts are where federal cases begin, with judges or juries determining facts and applying relevant law. Typically, a case in a district court is heard by one judge.

Courts of Appeals: The 13 regional circuit courts of appeals (including the D.C. Circuit and the Federal Circuit) review decisions from district courts within their geographic jurisdiction. Appeals courts typically hear cases in three-judge panels, focusing on whether district courts properly applied the law rather than reexamining factual determinations. Their primary function is to ensure consistency in federal law application across district courts. Typically, a case in one of the courts of appeals is heard by a three judge panel.

Supreme Court: As the highest judicial authority, the Supreme Court has final review power over federal cases and state cases involving federal questions. With nine justices, the Court primarily operates as an appellate body, choosing which cases to hear through the certiorari process (a fancy name for the Court’s choice to hear a case). Its decisions establish binding precedent for all lower federal courts and state courts on matters of federal law. Typically, all nine justices hear each case.

This three-tiered structure creates a system where most cases are resolved at lower levels, with only the most significant or controversial questions reaching the Supreme Court. It also allows for the development of legal doctrine through multiple stages of review, enabling different judges to consider the same legal questions before final resolution.

Jurisdiction of the Federal Courts

Federal courts have jurisdiction over (i.e., the authority to hear and decide) specific types of cases:

Federal question jurisdiction: Cases involving the Constitution, federal laws, or treaties.

Diversity jurisdiction: Civil cases between citizens of different states where the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000.

Other specialized jurisdictions: Such as piracy, bankruptcy, and cases where the United States is a party.

The federal system adjudicates only those matters specifically assigned to it by the Constitution or by Congress acting within constitutional bounds.

The Geographic Organization of Federal Courts

The federal judiciary's geographic organization reflects both practical considerations and historical compromises. District courts are distributed across all states and territories, with boundaries generally following state lines. This distribution ensures that federal justice is accessible throughout the nation while respecting state territorial integrity. The courts of appeals are organized into circuits that encompass multiple states, creating regional judicial authorities.

The geographic basis of the federal court system was deliberately designed to alleviate early Americans' fears about a centralized national judiciary. When the First Congress established the federal court system through the Judiciary Act of 1789, many citizens viewed a powerful, distant federal judiciary with suspicion and concern. Americans were wary of concentrating judicial power in a single, national institution far removed from local communities. By ensuring courts were local and heard cases with attention to regional circumstances and traditions, the system was made less threatening to Americans than a centralized judiciary in the nation's capital would have been. This geographic distribution of courts has remained a core feature of the federal judicial system, even as it has expanded and evolved.

The location of federal courts can affect the outcome of legal cases in a way that many Americans might not realize. This happens through what legal experts call venue shopping, when people filing lawsuits try to have their cases heard in specific regions where they think judges might be more sympathetic to their arguments.

Different regions of the country tend to develop their own legal cultures and approaches to interpreting the law. Additionally, since presidents appoint federal judges, and these appointments happen unevenly across the country over time, some regions end up with more judges appointed by Republican presidents while others have more appointed by Democratic presidents. For example, the Ninth Circuit (covering Western states including California) has historically been considered more liberal, while the Fifth Circuit (covering Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi) tends to be more conservative. When people have a choice about where to file their lawsuits, such as a national company with offices in multiple states or a non-profit organization challenging a federal law with potential plaintiffs across the country, they often consider these regional differences and try to choose the location most likely to rule in their favor.

For example, the 2023 lawsuit challenging the FDA's approval of mifepristone (an abortion medication) was deliberately filed in Amarillo, Texas, where a local court order assigns 95% of federal civil cases to a single judge—Matthew Kacsmaryk, who was appointed by former President Trump and had a history of opposing abortion. Although the judge ruled against those challenging the drug, they nonetheless strategically filed their case in Texas to try to maximize their chances of success.

Judicial Selection and Ideological Influence

The Appointment Process

The Constitution establishes that federal judges are appointed by the president "with the Advice and Consent of the Senate." This process was designed to balance democratic accountability with judicial independence—judges are selected through political mechanisms but then insulated from further political pressure once appointed.

The appointment process involves several stages:

Presidential nomination: The president selects nominees based on various factors including ideology, professional qualifications, diversity considerations, and political calculations.

Senate Judiciary Committee review: Nominees submit extensive documentation and participate in hearings where senators question them about their backgrounds, judicial philosophy, and views on significant legal issues.

Committee vote: The committee votes on whether to recommend the nominee to the full Senate.

Senate confirmation: The full Senate debates and votes on the nomination, with a simple majority required for confirmation.

Throughout American history, this process has evolved significantly. For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, "senatorial courtesy" gave substantial deference to home-state senators in the selection of district court judges, moderating ideological extremes. However, as partisan polarization has intensified, the confirmation process has become increasingly contentious.

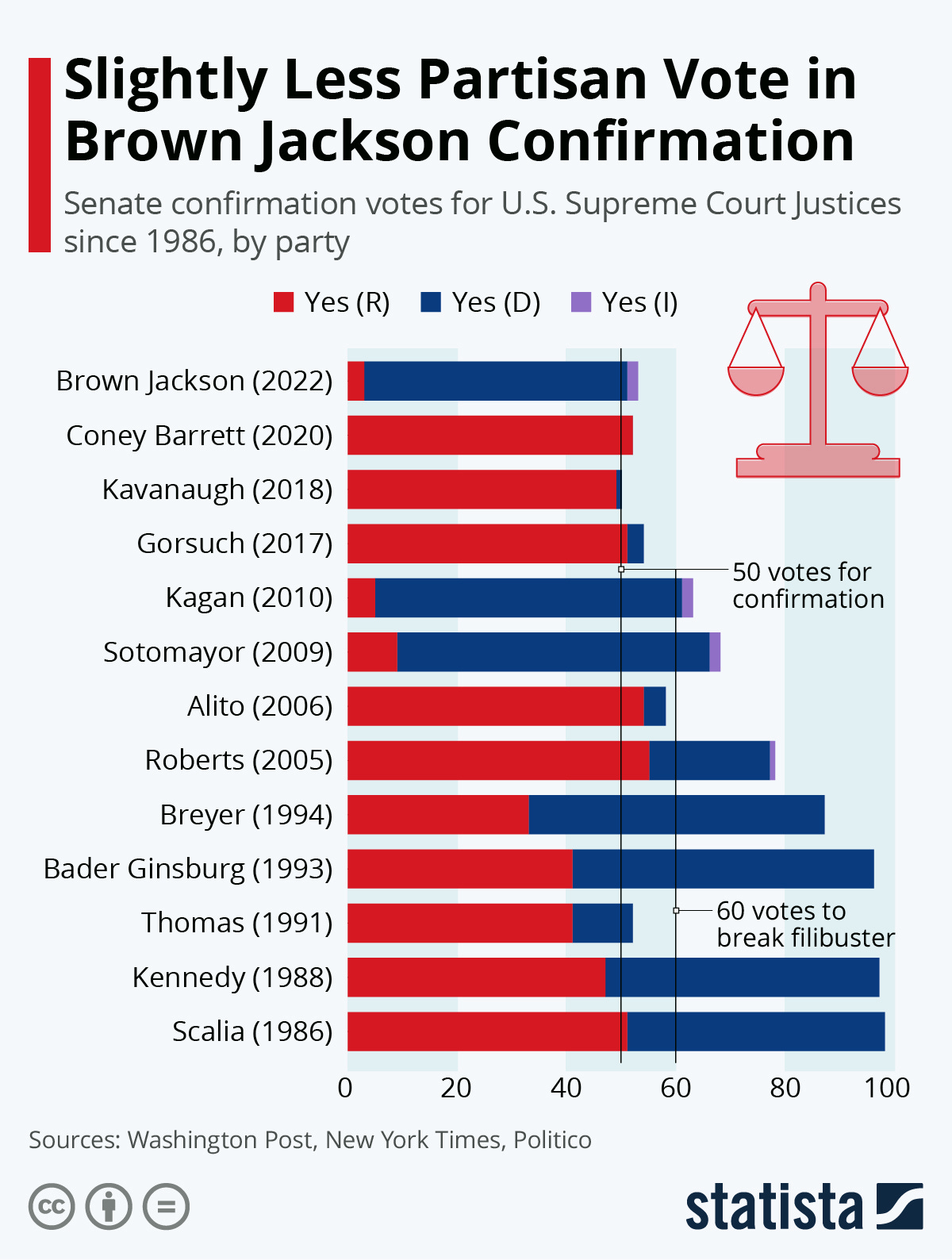

A pivotal change occurred in 2013 when Senate Democrats, frustrated by Republican obstruction of Obama administration nominees, employed the "nuclear option" to eliminate the filibuster for lower court appointments. Republicans extended this change to Supreme Court nominations in 2017 during the confirmation of Neil Gorsuch. These procedural modifications lowered the effective threshold for judicial confirmation from a supermajority of 60 votes to a simple majority, making it easier for presidents to appoint judges when their party controls the Senate.

To understand the significance of these changes, it's important to grasp how the filibuster works in the Senate. Unlike the House of Representatives, which operates by simple majority rule, the Senate has traditionally allowed for extended debate that can only be ended through a "cloture" vote requiring 60 out of 100 senators. This rule effectively meant that any judicial nominee needed support from at least some senators of the opposing party to be confirmed. The filibuster thus served as a moderating influence on judicial appointments, encouraging presidents to nominate judges with broader appeal rather than those appealing primarily to their partisan base.

When Senate Democrats grew frustrated with what they viewed as unprecedented Republican obstruction of Obama's nominees to lower federal courts and executive positions, they took the extraordinary step of changing Senate rules to allow these appointments to proceed with just 51 votes—the so-called "nuclear option," named because it was seen as a drastic measure that would permanently alter the Senate's deliberative character. Four years later, when Republicans controlled both the Senate and presidency, they expanded this rule change to include Supreme Court nominees, enabling the confirmation of Justice Gorsuch and subsequent Trump nominees with narrow partisan majorities. This procedural shift has accelerated the judiciary's ideological polarization, as presidents now have greater ability to appoint judges without needing to compromise to attract votes from the opposition party.

The Politics of Supreme Court Nominations

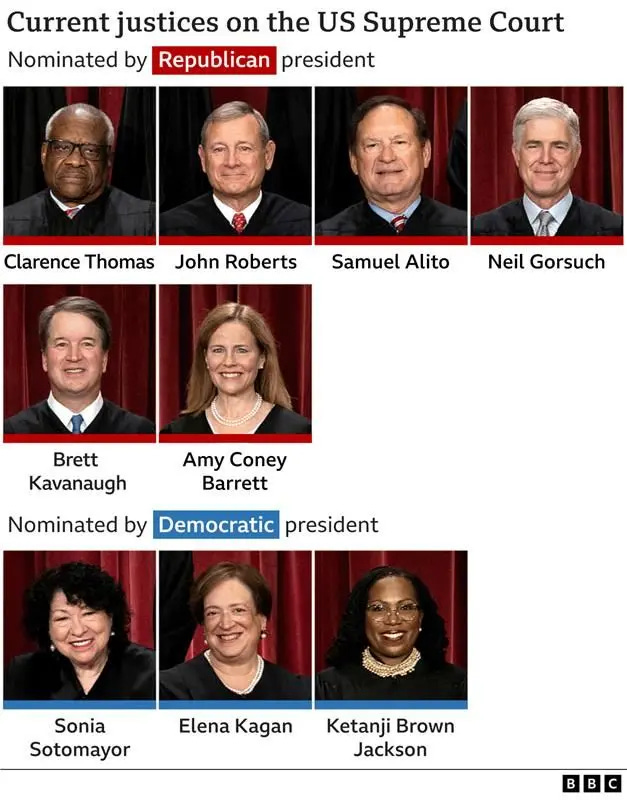

Supreme Court nominations have become increasingly politicized as both parties recognize the Court's pivotal role in resolving contested policy questions. Presidents strategically select nominees who share their ideological outlook and are young enough to have lengthy tenures, maximizing their long-term influence on constitutional interpretation.

The Senate confirmation process has similarly become more contentious, with extensive questioning about nominees' views on specific legal issues and heated partisan battles over controversial candidates. This politicization reached new heights with events like:

The Senate's refusal to consider President Obama's nomination of Merrick Garland in 2016.

The contentious confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh amid allegations of sexual misconduct in 2018.

The rushed confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett just before the 2020 presidential election.

These episodes reflect the growing importance of Supreme Court composition in partisan calculations. With many significant policy disputes ultimately resolved through judicial review, control of the Court has become a central prize in political competition between the parties.

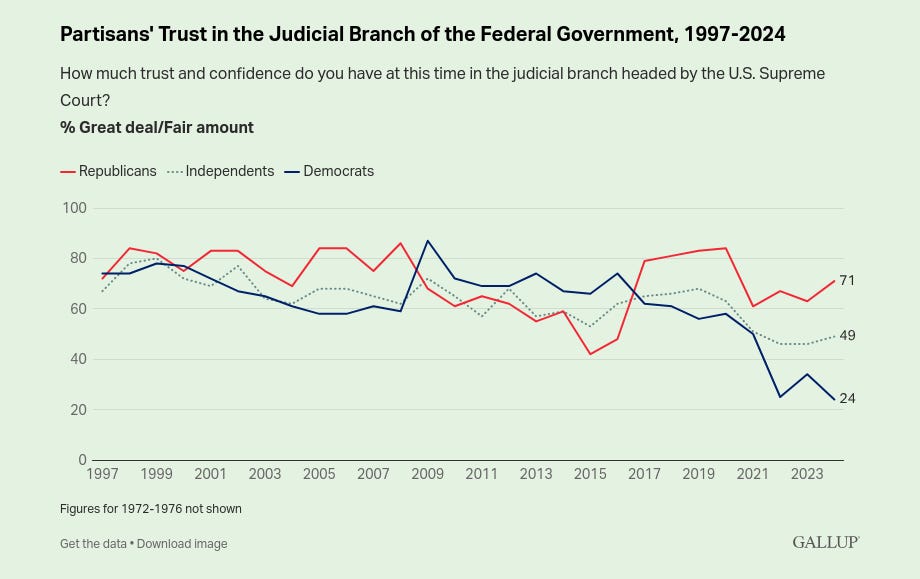

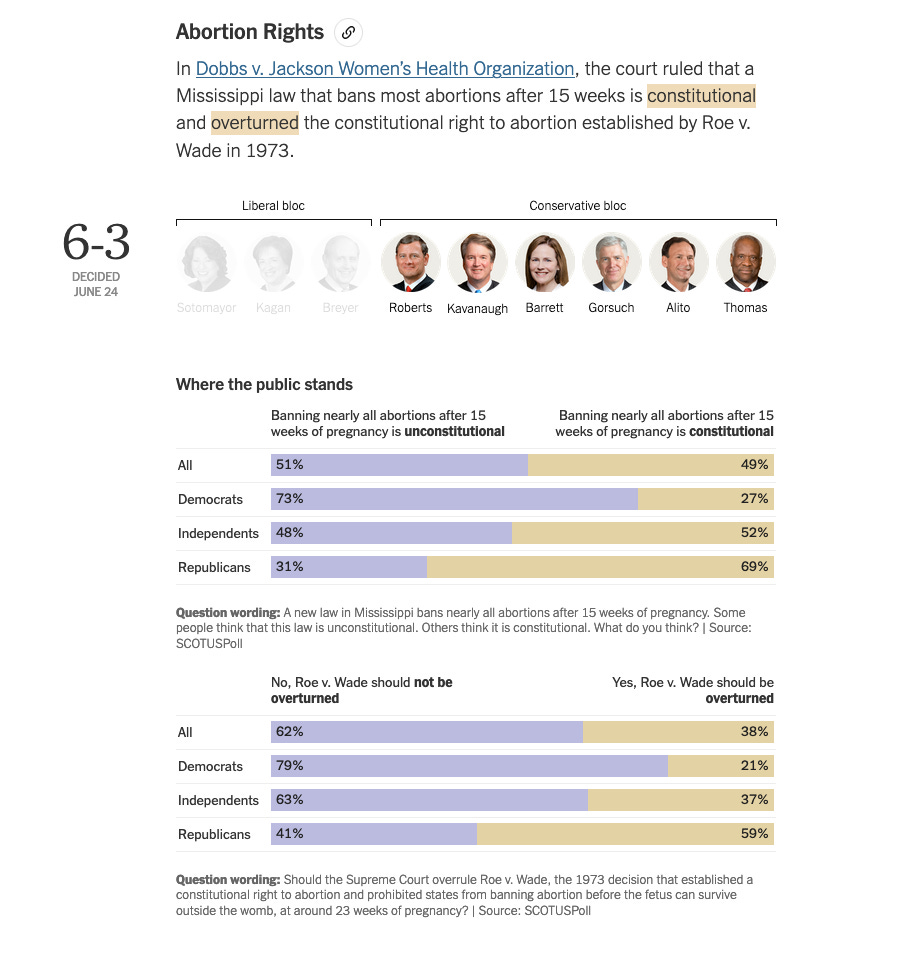

This politicization creates challenges for judicial legitimacy. If justices are increasingly perceived as partisan actors rather than impartial arbiters, public confidence in the Court may erode. Recent polling shows precisely this trend, with public approval of the Supreme Court increasingly divided along partisan lines, particularly following controversial decisions like Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization (2022), which overturned the constitutional right to abortion established in Roe v. Wade (1973).

Getting to the Supreme Court

As the highest judicial authority, the Supreme Court has final review power over federal cases and state cases involving federal questions. With nine justices, the Court primarily operates as an appellate body, choosing which cases to hear through what is called the certiorari process (or granting cert). Its decisions establish binding precedent, the rules for deciding on similar future cases, for all lower federal courts and state courts on matters of federal law.

This three-tiered structure creates a system where most cases are resolved at lower levels, with only the most significant or controversial questions reaching the Supreme Court. It also allows for the development of legal doctrine through multiple stages of review, enabling different judges to consider the same legal questions before final resolution.

The Supreme Court exercises substantial discretion in selecting which cases to hear. Of the approximately 8,000 petitions for certiorari filed annually, the Court typically accepts only about 60-70 cases. This selectivity allows the Court to focus on cases that:

Resolve conflicts between lower federal courts.

Clarify important federal laws.

Address significant constitutional questions.

Present issues of exceptional national (or partisan) importance.

The "Rule of Four" governs this selection process—at least four justices must vote to grant certiorari for a case to be heard. This rule ensures that a significant minority of the Court can bring cases forward even if the majority might be reluctant to address certain issues.

The Process of Supreme Court Decision-Making

When the Supreme Court accepts a case for review, it engages in a multi-stage deliberative process:

Briefs and arguments: The parties submit written briefs outlining their legal arguments, and outside groups may file amicus curiae ("friend of the court") briefs offering additional perspectives. Oral arguments follow, where attorneys present their cases and respond to justices' questions.

Conference discussion: In private conference, justices discuss the case and take a preliminary vote. The Chief Justice assigns the majority opinion if in the majority; otherwise, the most senior justice in the majority makes the assignment. The power to assign opinions represents a significant strategic tool for the Chief Justice or senior justice in the majority. This assignment can shape the scope, reasoning, and ultimate impact of the Court's decision. For example, a Chief Justice might assign a controversial opinion to a moderate colleague to ensure a narrower ruling, or to themselves to maintain greater control over the outcome.

Opinion writing: The assigned justice drafts a majority opinion articulating the Court's reasoning. Other justices may write concurring opinions (agreeing with the outcome but offering different reasoning) or dissenting opinions (disagreeing with the outcome). However, only the majority opinion will matter for future interpretation of the law.

Opinion circulation and revision: Draft opinions circulate among the justices, who may suggest revisions or decide to join or withdraw from particular opinions based on their content.

Final decision: When the process concludes, the Court announces its decision and publishes the accompanying opinions, which establish binding precedent for lower courts.

This process combines legal analysis, strategic calculation, and interpersonal negotiation. Justices must craft opinions that maintain the support of their colleagues while establishing doctrinal frameworks they find persuasive. The need to secure majority support often requires compromise on reasoning or scope, as illustrated by Chief Justice Roberts' opinion upholding the Affordable Care Act in NFIB v. Sebelius (2012). Chief Justice Roberts was the lone conservative judge to vote with the four Democratic justices, but he assigned the majority opinion to himself. Here, Roberts employed reasoning more aligned with conservative jurisprudence, yet the more liberal justices had to accept Robert’s reasoning if they wanted to win on the case.

How Do Judges Make Decisions

The notion that judges simply "call balls and strikes" according to neutral legal principles is not supported by empirical research or practical observation. When Chief Justice Roberts used this baseball metaphor during his confirmation hearings, he presented an idealized vision of judging that contrasts with the reality of how judges actually decide cases.

Research on judicial decision-making identifies three potential influences on how judges rule:

The Legal Model: This traditional view holds that judges decide cases by objectively applying legal text, precedent, and established interpretive methods. Under this model, properly trained judges examining the same legal materials should reach similar conclusions regardless of their personal backgrounds or beliefs. Legal education, professional norms, and the obligation to provide reasoned explanations for decisions all reinforce this approach.

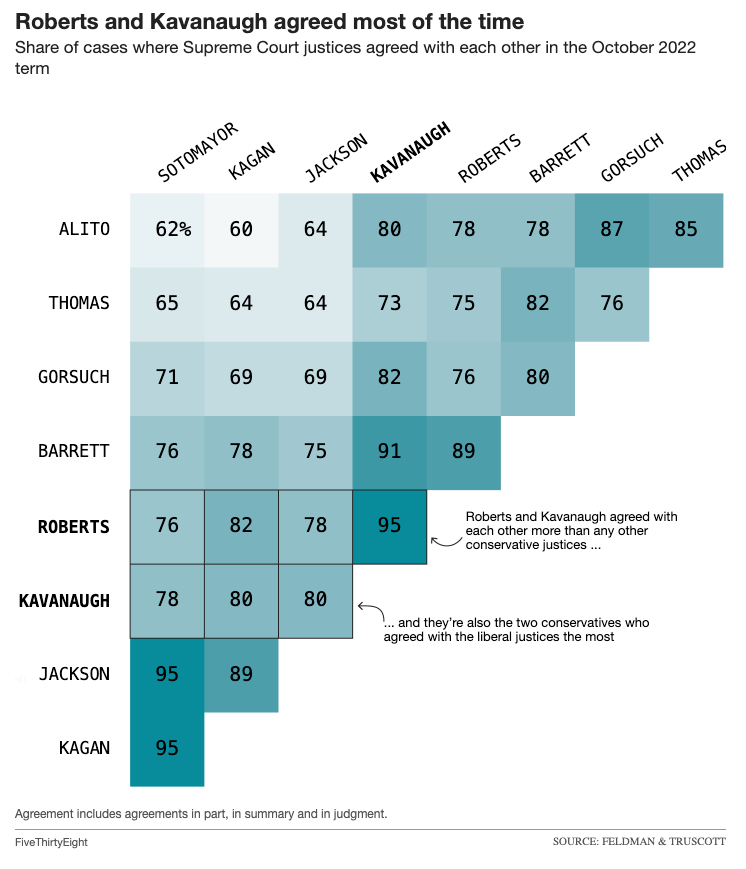

Ideological Influences: Despite the legal model's appeal, empirical studies consistently find that judges' ideological leanings predict their voting patterns, particularly in politically salient cases. Supreme Court voting alignments often reflect clear ideological divisions that persist across different legal issues. For example, the current Supreme Court's conservative justices (appointed by Republican presidents) frequently vote together in cases involving abortion, affirmative action, and regulatory authority, while the liberal justices (appointed by Democratic presidents) align on the opposite side. These patterns suggest that judicial decision-making involves more than neutral application of legal principles.

Public Opinion: While judges are insulated from direct electoral accountability through life tenure, research indicates they remain responsive to broader public sentiment, particularly on high-profile issues. This responsiveness may reflect concerns about institutional legitimacy, as the judiciary depends on public acceptance for its authority. Some studies suggest that Supreme Court decisions rarely deviate far from mainstream public opinion for extended periods. However, in cases like Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization (2022), which overturned abortion rights established in Roe v. Wade, the Court demonstrated its willingness to rule against majority public opinion on certain issues.

The influence of these factors varies depending on the case and context. While legal training and professional norms should constrain naked ideological decision-making, the inherent ambiguity in many constitutional provisions and statutes creates space for judges' values and preferences to shape their interpretations. Understanding these influences helps explain why judicial appointments have become increasingly contentious political battles—participants recognize that who serves on the courts significantly affects how laws are interpreted and constitutional rights defined.

Precedent and Legal Development

When the Supreme Court decides a case, it does more than simply resolve the specific dispute before it—it creates precedent that shapes how lower courts will decide similar cases in the future. Supreme Court decisions establish binding nationwide rules that all lower federal courts must follow, while federal courts of appeals create precedents binding within their geographic circuits. Through this hierarchical system, a relatively small number of Supreme Court decisions can have far-reaching effects, influencing thousands of cases across the federal judiciary and state courts. The power to establish precedent makes the Supreme Court not just an arbiter of individual disputes but a creator of legal doctrine that evolves over time through the accumulation of decisions in related areas of law.

The principle of stare decisis ("let the decision stand") encourages courts to follow established precedents—prior court decisions that serve as authoritative examples in similar future cases—rather than reconsidering settled questions in each case. This doctrine promotes legal stability and enhances the perceived legitimacy of judicial decisions by reducing the appearance of arbitrary judgment.

Although lower courts must follow Supreme Court precedent, the Supreme Court maintains the authority to overrule its own precedents when appropriate. The Court's approach to precedent has evolved over time, with recent court terms showing increased willingness to reconsider established doctrines. The Dobbs decision marked a particularly significant departure from traditional stare decisis principles by overturning a nearly 50-year precedent that had been repeatedly reaffirmed.

Conclusion: The Judiciary's Democratic Role

The federal judiciary occupies a paradoxical position in American democracy. It exercises significant power despite its members never facing direct election, potentially undercutting democratic governance. Yet it also serves essential democratic functions by protecting constitutional rights, maintaining the rule of law, and checking majority excesses.

This tension—between democratic responsiveness and constitutional principle—defines the judiciary's role in American government. Courts must balance majority rule with individual rights, immediate preferences with enduring values, and political accountability with principled independence. This balancing act becomes particularly challenging in periods of intense polarization, when constitutional interpretation increasingly aligns with partisan divisions.

The judiciary's effectiveness ultimately depends on maintaining legitimacy—the public's acceptance of courts as appropriate authorities for resolving constitutional disputes. This acceptance requires that judicial decisions be perceived as principled rather than purely political, even when they involve contested values or policy implications.

Perhaps the judiciary's greatest strength lies in its institutional distinctiveness from the political branches. When functioning ideally, courts provide forums where disputes are resolved through reasoned argument rather than political power, where constitutional principles constrain democratic majorities, and where individual rights receive protection even against popular preferences.

Maintaining this distinctive judicial role in a polarized era is challenging. If courts become perceived as merely another partisan battlefield, their authority to resolve constitutional disputes may erode. Yet if they retreat entirely from contested issues to preserve institutional legitimacy, they risk abdicating their constitutional responsibility to enforce constitutional constraints. The judiciary's future legitimacy depends on whether it can maintain this delicate balance—exercising principled judgment while respecting democratic governance, applying constitutional constraints while acknowledging democratic legitimacy.

Key Terms

Judicial review: The power of courts to declare legislative and executive actions unconstitutional.

Marbury v. Madison: The 1803 Supreme Court case that established judicial review.

Certiorari: The process through which the Supreme Court decides which cases to hear.

Rule of Four: The practice requiring four justices to vote to grant certiorari for the Supreme Court to hear a case.

Stare decisis: The principle that courts should generally follow established precedents.

Venue shopping: The strategic filing of cases in jurisdictions perceived as favorable to particular legal positions.

Majority opinion: The official explanation of a court's ruling, which establishes binding precedent.

Dissenting opinion: A separate opinion explaining disagreement with the majority's conclusion.

Nuclear option: The procedural change in 2013 eliminating the filibuster for judicial nominations.