How to Think Like a Political Scientist

Understanding how politics works: from individual preferences to collective action.

Learning Objectives

Define political science as a field of study

Understand the core components of political behavior and decision-making

Identify major collective action problems in political systems

Explain how institutions help solve coordination problems in politics

Analyze the purpose and functions of government in addressing collective problems

Introduction: The Political World Around Us

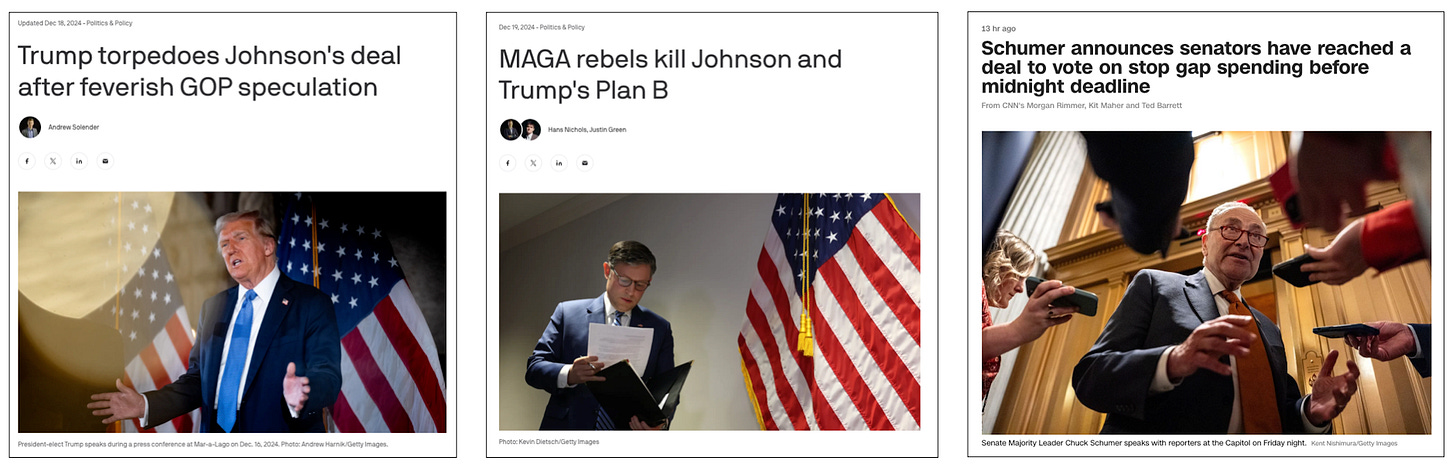

On a cold January day in 2024, the United States government came perilously close to a shutdown. As the deadline for funding federal operations approached, lawmakers scrambled to reach an agreement. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson initially proposed a bipartisan continuing resolution to keep the government running, but faced criticism from former President Donald Trump and influential conservatives. After a series of negotiations and competing proposals, Congress eventually passed a narrower continuing resolution with broad bipartisan support, averting the shutdown.

This episode illustrates a fundamental reality of politics: reaching collective decisions is difficult, even when the stakes are high and the consequences of inaction are severe. Throughout this chapter, we'll explore why political decision-making is so challenging and how political scientists approach the study of political behavior. By examining the core concepts of preferences, institutions, and collective action problems, we'll develop a framework for understanding how our political system functions—and why it sometimes doesn't.

Defining Politics: More Than Just Government

What is “politics?”

"The process through which individuals and groups seek agreement on a course of common, or collective, action—even as they disagree on the intended goals of that action." (Kernell et al. 2023)

"Who gets what, when, and how." (Harold Lasswell 1936)

A group of participants with their own preferences negotiating complex and divisive issues.

These definitions share a common theme: politics is about how groups make collective decisions despite having different preferences. It's the process through which societies resolve disagreements and determine a course of action. Politics is not limited to government—it occurs in families, workplaces, student organizations, and any setting where people must make decisions together.

Consider the annual federal budget process. Each year, the president and Congress must agree on 12 funding bills that allocate money for everything from defense to healthcare to environmental protection. With so many competing priorities and limited resources, reaching agreement is extraordinarily difficult. In fact, for nearly 30 years, Congress has failed to pass all appropriations bills by the September 30 deadline, leading to continuing resolutions or government shutdowns.

The Science in Political Science

While politics is about the practice of collective decision-making, political science aims to identify patterns in the political world and explain why they occur. Political science differs from related fields in important ways. Consider how each discipline might approach a major piece of legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964:

A civics course explains the formal process: committee hearings, floor debates, presidential signature.

A history course examines the specific context: Martin Luther King Jr.'s activism, President Johnson's leadership, changing public attitudes.

Political science looks for broader patterns: What conditions generally make transformative legislation possible?

Political scientists notice, for instance, that major laws like the Civil Rights Act, the Affordable Care Act, and New Deal legislation all passed during periods of unified government—when one party controlled both Congress and the presidency. By analyzing many cases, they identify patterns that explain political outcomes beyond any single event.

Further Reading:

The Foundation of Political Science: Rational Actors and Preferences

Political science begins with a fundamental assumption: all political behavior has a purpose. Nothing happens by accident or randomly. Individuals have goals and preferences, and they take actions to pursue those goals.

Rational Actors

Political scientists often describe individuals as "rational actors." This doesn't necessarily mean people are smart or correct in their decisions. Rather, it means that people:

Have goals they want to achieve.

Take actions they believe will help them achieve those goals.

Make decisions based on the information available to them.

Consider how others might react to their actions.

Even actions that might seem irrational to outsiders often make sense when viewed through the lens of an individual's specific goals and constraints.

Preferences in Politics

Preferences are simply what individuals or groups want—their desired outcomes. Some people prefer lower taxes and fewer government services; others prefer higher taxes and more extensive public programs. Some voters prefer conservative candidates; others prefer progressive ones.

If everyone shared the same preferences, politics would be unnecessary. But in reality, preferences differ widely, creating the need for processes to reconcile these differences and reach collective decisions. This reconciliation often requires bargaining and compromise—the heart of politics.

Government: Institutions for Collective Decisions

If politics involves reconciling different preferences to reach collective decisions, then how do societies manage this process? Throughout history, humans have developed increasingly sophisticated institutions to structure political interactions and resolve conflicts without resorting to violence. These institutions—collectively known as government—establish rules, procedures, and enforcement mechanisms that help overcome the collective action problems inherent in group decision-making.

The Foundations of Government: From Chaos to Order

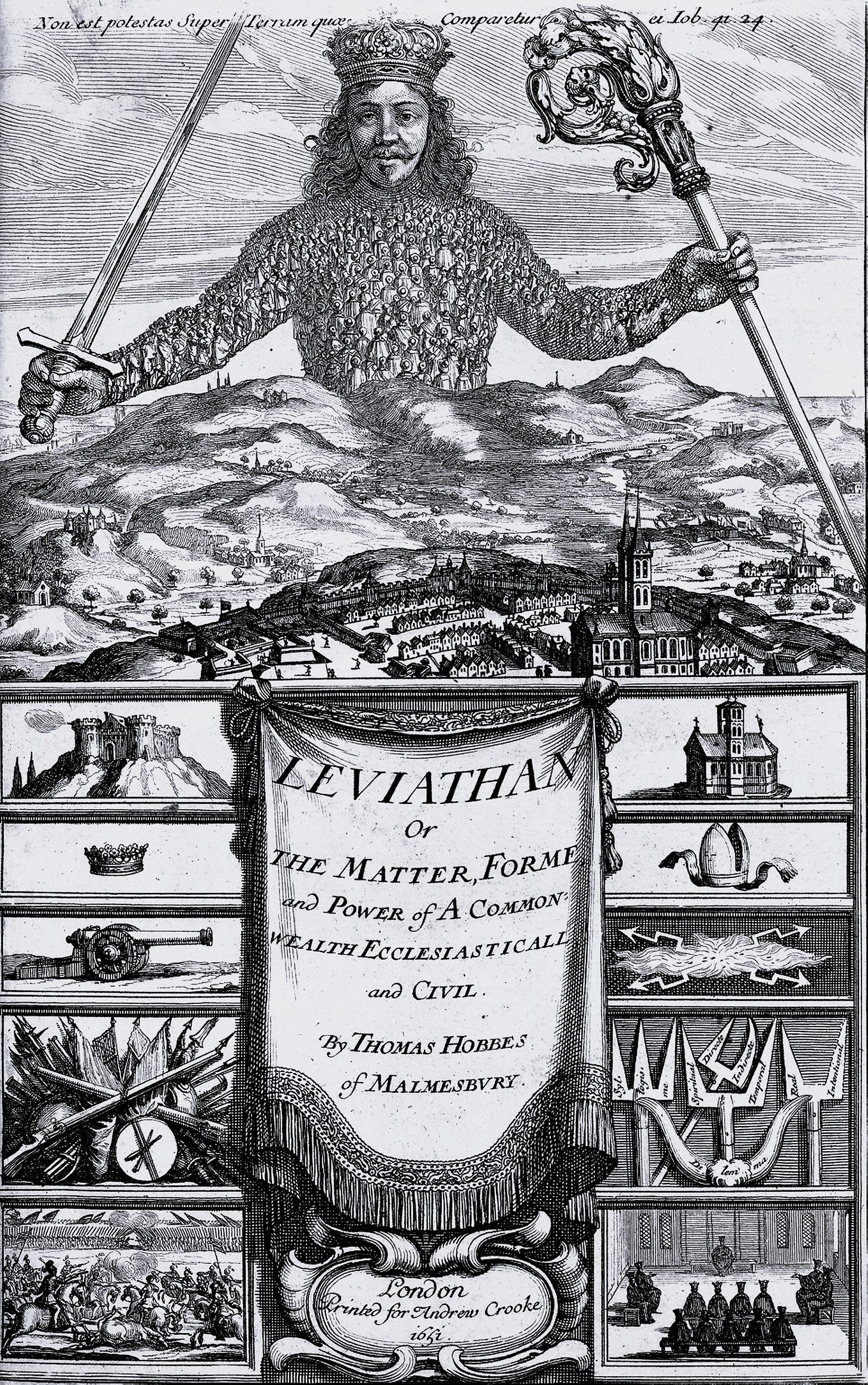

To understand why governments exist in the first place, political scientists often look to early political philosophers who imagined what life would be like without any formal political authority. One of the most influential of these thinkers was Thomas Hobbes, an English philosopher who lived during the tumultuous period of the English Civil War in the 17th century.

In his 1651 work, Leviathan, Hobbes posed a fundamental question: Why would individuals, who naturally value their freedom, agree to submit to government authority? To answer this, he asked readers to imagine a "state of nature"—a hypothetical condition where no government or common authority exists. In such a state, Hobbes argued, everyone would have complete freedom, but this freedom would come at a terrible price.

Without government to protect property rights or enforce agreements, Hobbes reasoned that people would live in constant fear. No one could trust others to keep their word, respect property boundaries, or refrain from violence. Everyone would need to protect themselves by whatever means necessary. Under these conditions, Hobbes famously described life as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

Hobbes's solution was what he called a "social contract," where individuals voluntarily surrender some of their natural freedom to a sovereign authority—what we now call government—in exchange for security and order. By establishing common rules and enforcement mechanisms, government makes cooperation possible and protects individuals from the dangers of unrestrained self-interest.

This idea of government as a solution to collective problems remains central to political science. While few modern scholars accept all of Hobbes's conclusions (particularly his preference for absolute monarchy), his insight that government emerges from the need to solve collective action problems continues to shape how we understand political institutions.

What Is Government?

Government is the set of institutions and procedures for making and enforcing collective agreements. All organizations have rules and procedures for making decisions, from classroom policies to fraternity bylaws. What distinguishes government is its scope and authority over an entire political community.

In the United States, the Constitution establishes the basic framework for government, creating the institutions and rules for making collective decisions. An institution is an organization that helps manage conflict between competing interests through established procedures. These procedures create predictability, establish legitimacy, and provide mechanisms for resolving disputes without resorting to force.

The American system features several key political institutions, each designed to structure political conflict in different ways:

The House of Representatives manages conflict through majoritarian rules and proportional representation based on population. With 435 members serving two-year terms, the House channels popular sentiment while using institutional features like committees, leadership positions, and procedural rules to organize decision-making among hundreds of representatives.

The Senate balances state interests by providing equal representation (two senators per state) regardless of population. Its longer six-year terms, smaller size (100 members), and different procedural rules (including the filibuster) create a deliberative body that often serves as a check on more volatile majoritarian impulses.

The Presidency creates a single national office that can act decisively while remaining accountable to voters. The president's ability to coordinate across agencies, command the military, and speak with a unified voice helps overcome coordination problems inherent in collective action.

The Supreme Court resolves constitutional disputes through reasoned interpretation rather than political bargaining. By establishing precedents that guide future decisions, the Court provides stability and predictability in how rules are applied over time.

Each of these institutions has formal powers defined by the Constitution, but also operates according to informal norms, traditions, and practices that have evolved over time. Together, they create a complex system of checks and balances that structures political conflict without eliminating it entirely—channeling disagreement into productive paths rather than destructive ones.

Collective Action Problems

Even with established institutions, reaching collective decisions remains challenging. The fundamental problem of politics is that what's best for individuals doesn't always align with what's best for the group as a whole. A dictator might resolve disagreements by decree, but democratic systems require building agreement among many actors with different preferences. This creates what political scientists call collective action problems—situations where achieving a desirable collective outcome is difficult due to individual incentives.

Types of Collective Action Problems

Political scientists have identified several major collective action problems that help explain why politics is so challenging:

1. Coordination Problems

The larger a group becomes, the harder it is to coordinate action, even when everyone agrees on the goal. In a country of 330 million people, coordinating collective action without some organizing structure would be virtually impossible.

Institutions help solve coordination problems by establishing procedures, rules, and focal points. For example:

Representative democracy reduces the number of decision-makers from millions of citizens to hundreds of legislators.

Legislative rules create orderly procedures for debate and voting in Congress.

Party organizations help like-minded legislators propose and pass an agenda.

Committee systems divide labor and create expertise.

These institutional features create what game theorists call focal points—default options that help coordinate behavior without explicit communication. For instance, when Congress needs to pass emergency legislation, members know where and when to gather without having to coordinate individually with 534 other legislators.

2. Free Riding

Free riding occurs when individuals benefit from collective action without contributing to it. For example, consider a Republican senator from a moderate state like Susan Collins of Maine. While she generally supports Republican priorities, she sometimes breaks with her party on high-profile votes where supporting the party line might harm her reelection prospects. By appearing "independent," she benefits from Republican support in areas like committee assignments while avoiding the electoral costs of unpopular party positions.

Other examples of free riding include:

Climate change action: Everyone benefits from reduced emissions, but individuals face costs for changing their own behavior.

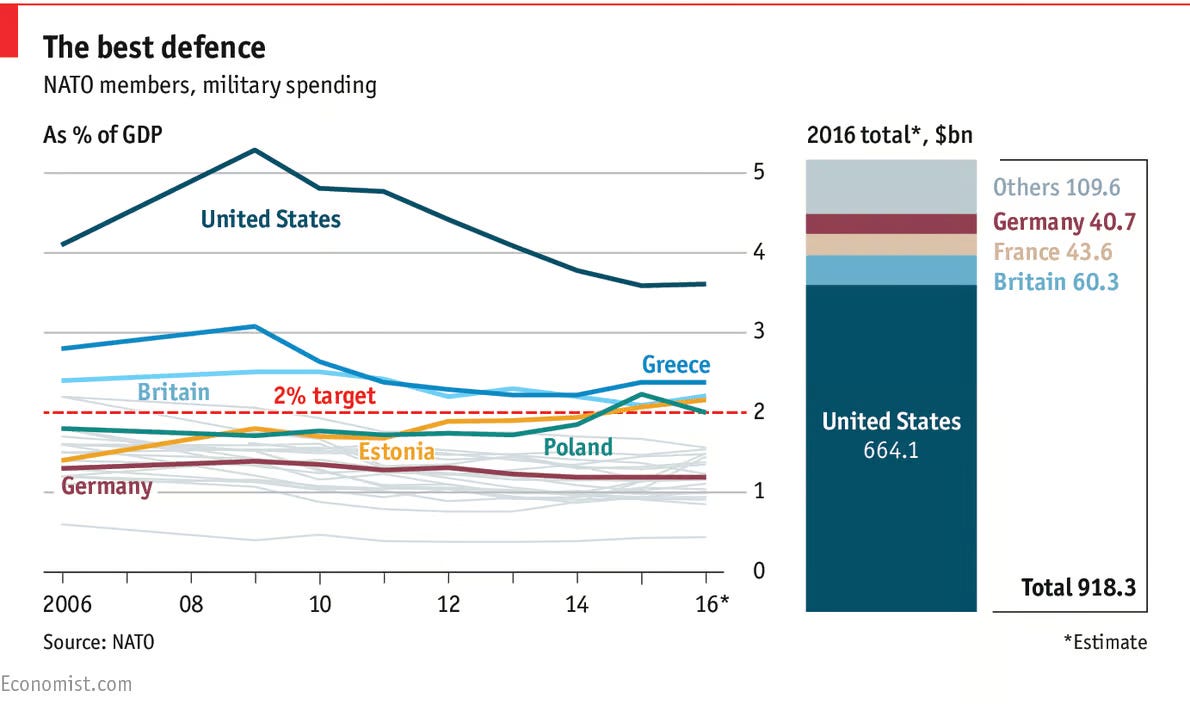

NATO defense spending: All member nations benefit from collective security, but some contribute less than their agreed share, relying on others' contributions.

Free riding creates a paradox: if everyone tries to free ride, the collective benefit disappears for everyone. This helps explain why voluntary collective action often fails without institutional mechanisms to ensure compliance.

3. Prisoner's Dilemma

The prisoner's dilemma describes situations where individuals acting in their own self-interest produce worse outcomes than if they had cooperated.

The classic example involves two prisoners interrogated separately, each offered the following deal:

If both remain silent: each gets 1 year of prison time.

If one betrays while other stays silent: betrayer goes free, other gets 20 years.

If both betray: each gets 5 years.

Although both would benefit from mutual silence, the fear of betrayal and temptation of going free often leads both to betray each other.

In politics, prisoner's dilemmas arise frequently:

Arms races: Nations would collectively benefit from limiting military spending, but each has an incentive to build up arms for strategic advantage

Environmental protection: Companies would collectively benefit from sustainable practices, but each has an incentive to cut costs through environmentally harmful methods

Healthcare mandates: The health insurance system works best when everyone participates, but individuals have incentives to wait until they're sick to purchase insurance

Government can help solve prisoner's dilemmas by creating institutions that enforce agreements. For example, the Affordable Care Act's individual mandate required everyone to purchase health insurance or pay a penalty, aligning individual incentives with the collective goal of a sustainable healthcare system.

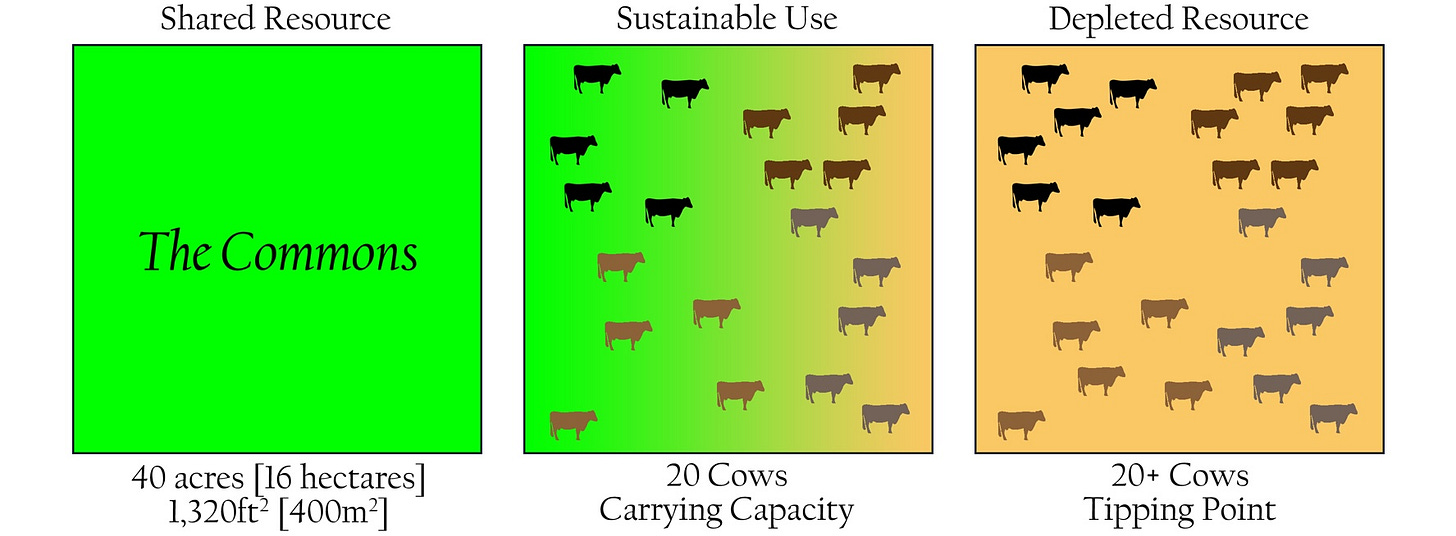

4. Tragedy of the Commons

The tragedy of the commons occurs when individuals, acting in their own self-interest, deplete or degrade a shared resource. The classic example involves farmers grazing cattle on common land. Consider four farmers sharing grazing land:

Each starts with two cows.

Adding one cow increases an individual farmer's profit.

But if all farmers add cows, the land becomes overgrazed.

Eventually the degraded land can't support any cows and all suffer.

Modern examples include:

Overfishing: Each fishing crew benefits from catching more fish, but collective overfishing depletes fish stocks

Air pollution: Companies benefit from avoiding costly pollution controls, but collective pollution harms air quality for everyone

Office resources: When coffee is provided for free in a workplace, individuals might consume more than they would if paying themselves, potentially depleting supplies faster than budgeted

Governments address these problems through regulation (rules limiting resource use ensure that each individual only consumes their fair share) and privatization (assigning individual property rights to ensure that each individual will be a good steward of their personal property).

5. Principal-Agent Problem

The principal-agent problem arises when one party (the agent) is supposed to act on behalf of another party (the principal) but has incentives to pursue their own interests instead. In a representative democracy, voters (principals) elect representatives (agents) to act on their behalf, but representatives may sometimes prioritize their own goals over constituents' preferences.

For example:

A senator might vote for legislation favored by campaign donors even if most constituents oppose it.

A bureaucrat might implement a policy in a way that expands their agency's budget rather than maximizing efficiency.

A TA might show a movie in class rather than share the content her professor has asked her to teach.

Democratic institutions address the principal-agent problem through mechanisms like elections (allowing principals to replace agents who don't serve their interests), oversight committees, transparency requirements, and professional norms.

What Government Does

Given these collective action problems, what role does government play in political life? Government serves several key functions:

1. Solving Collective Action Problems

Government's primary purpose is to overcome the collective action problems described above. Through its authority to make and enforce rules, government can:

Coordinate action across large populations

Prevent free riding by requiring participation

Resolve prisoner's dilemmas by enforcing cooperation

Manage common resources through regulation or property rights

Align agent incentives with principal interests through elections and oversight.

2. Providing Public Goods

Public goods are benefits that everyone can consume regardless of whether they've contributed to their production, and one person's consumption doesn't reduce availability for others. Examples include national defense, clean air, public parks, and basic research. Because of free rider problems, markets typically underproduce public goods, creating a role for government provision.

3. Creating and Enforcing Rules

Government establishes the basic rules through which individuals and groups interact. By defining rights, responsibilities, and procedures, government creates a framework for resolving disputes and reaching collective decisions without resorting to force.

Conclusion: Politics as Purposeful Behavior

Political scientists begin from the premise that "all political behavior has a purpose" (Lowi et al). This insight is central to thinking like a political scientist. Even when political outcomes seem chaotic or irrational, they typically reflect purposeful actions by individuals responding to institutional incentives and constraints.

Understanding these incentives and constraints helps explain why politics often fails to produce seemingly obvious solutions to collective problems. It's not because politicians are uniquely incompetent or corrupt, but because the very nature of collective decision-making creates inherent challenges.

By examining politics through the lens of preferences, institutions, and collective action problems, political scientists seek not just to describe political systems but to explain why they work the way they do—and how they might be improved.

Key Terms

Politics: The process through which individuals and groups seek agreement on a course of common action despite disagreeing on intended goals.

Political science: The study of generalizable patterns in political behavior and the effort to explain why they occur.

Preferences: What individuals or groups want—their desired outcomes.

Rational actor: An individual who pursues goals based on available information and anticipated reactions.

Institution: An organization that helps manage conflict between competing interests through established procedures.

Government: The set of institutions and procedures for making and enforcing collective agreements.

Collective action problems: Situations where achieving a desirable collective outcome is difficult due to competiting individual incentives.

Free riding: Benefiting from collective action without contributing to it.

Prisoner's dilemma: A situation where individuals acting in their self-interest produce worse outcomes than if they had cooperated.

Tragedy of the commons: The depletion of a shared resource by individuals acting in their self-interest.

Principal-agent problem: An agent entrusted to act on behalf of a principal may have incentives to pursue their own interests instead of what the principal would like.

Public goods: Benefits that everyone can consume regardless of contribution, and where one person's consumption doesn't reduce availability for others.