Is the "Deep State" Real?

Expertise, accountability, and the dilemma of administrative power in the US bureaucracy.

Learning Objectives

Understand the historical development of the American bureaucracy and its changing relationship to democratic governance.

Analyze the tension between expertise and democratic accountability in bureaucratic administration.

Identify the formal and informal powers of the bureaucracy in the policymaking process.

Evaluate mechanisms of control over bureaucratic agencies by the three branches of government.

Introduction: The Bureaucracy in American Political Debate

"Either the deep state destroys America, or we destroy the deep state."

With these words at a 2023 rally in Waco, Texas, former President Donald Trump articulated a view held by many Americans—that an unelected bureaucracy wields excessive power in American governance, potentially undermining democratic accountability. This perspective isn't limited to one political party; liberals have long criticized the "military-industrial complex" for pushing the nation toward unnecessary conflicts, while conservatives have targeted regulatory agencies for imposing burdens on businesses. A 2018 Monmouth University poll found that a majority of Americans across the political spectrum believe a "deep state" exists that manipulates or directs national policy.

But what exactly is this "deep state"?

This provocative term refers to the federal bureaucracy—the sprawling network of departments, agencies, and offices staffed by both political appointees and career civil servants who implement laws and administer government programs. Unlike elected officials, most bureaucrats remain in government across multiple administrations, developing specialized expertise and institutional memory. This continuity provides stability in governance but also raises questions about democratic control and accountability. The bureaucracy embodies a fundamental tension in democratic governance: the need for expert administration versus the principle of popular sovereignty.

This chapter examines the development and operation of the American bureaucracy, exploring both its necessity for effective governance and the challenges it poses to democratic control. Rather than accepting simplistic narratives about a shadowy "deep state," we will analyze how the bureaucracy's structure, powers, and relationship to elected officials have evolved over time. By understanding these complexities, we can better evaluate contemporary debates about bureaucratic power and democratic accountability.

The Necessity of Bureaucracy: Why Laws Are Not Self-Executing

When Congress passes a law or the president issues an executive order, the text itself does not automatically translate into action. Laws and directives must be interpreted, implemented, and enforced—tasks that require organization, expertise, and resources beyond what elected officials can provide directly.

Consider President Trump's 2024 executive order restricting birthright citizenship. While the order states that children born in the U.S. to non-citizen or non-permanent resident parents no longer automatically receive citizenship, it provides little guidance on implementation. Citizenship and Immigration Services officials face numerous practical questions: How will they verify parents' immigration status? What documentation is required? How does this change affect birth certificate procedures? The executive order creates policy in principle, but bureaucrats have to translate it into practice—developing systems, procedures, and guidelines that would affect millions of people.

This example illustrates why bureaucracy is unavoidable in modern governance. Laws and executive orders typically establish broad goals or standards rather than detailed instructions—partly due to political compromise, partly because legislators lack technical expertise, and partly to allow flexibility in implementation. The Clean Air Act, for instance, aims to reduce air pollution but delegates to the Environmental Protection Agency the technical work of defining acceptable pollution levels and establishing regulations to achieve them.

Delegation to bureaucratic agencies solves several governance problems:

Expertise: Legislators cannot possibly master the technical details of every policy area, from nuclear safety to food inspection. Agencies employ specialists with relevant knowledge and training.

Workload: Congress simply lacks the capacity to make all the detailed decisions required for implementing complex programs across the nation.

Flexibility: Bureaucratic rulemaking allows policies to adapt to changing circumstances without requiring new legislation for every adjustment.

Consistency: Administrative agencies can apply rules uniformly across jurisdictions, rather than leaving implementation to vary from state to state.

These advantages explain why delegation to bureaucratic agencies has expanded as governance has become more complex. However, this delegation creates tensions with democratic accountability, as unelected officials exercise significant discretion in shaping policy outcomes.

The Evolution of the American Bureaucracy

The American bureaucracy has evolved through three distinct periods, each reflecting different approaches to the tension between democratic control and administrative effectiveness.

Federalist Era (1789-1829): "Respectability"

Delegates at the Constitutional Convention approached executive power cautiously, having just fought a revolution against British colonial administration. The Constitution created executive departments but gave Congress significant control over their structure and authority. The First Congress established three departments—State, Treasury, and War—with senior officials appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. The federal bureaucracy of this era was small, focused on basic functions like delivering mail, collecting customs duties, and military organization.

President Washington established an approach to bureaucratic appointments based on "respectability" and competence. He selected officials from the social and economic elite, people he believed possessed the character and capabilities necessary for effective administration and who would help establish trust in the new American government. These officials typically retained their positions based on good behavior, regardless of partisan transitions. This approach prioritized administrative competence but limited representation to a narrow segment of society.

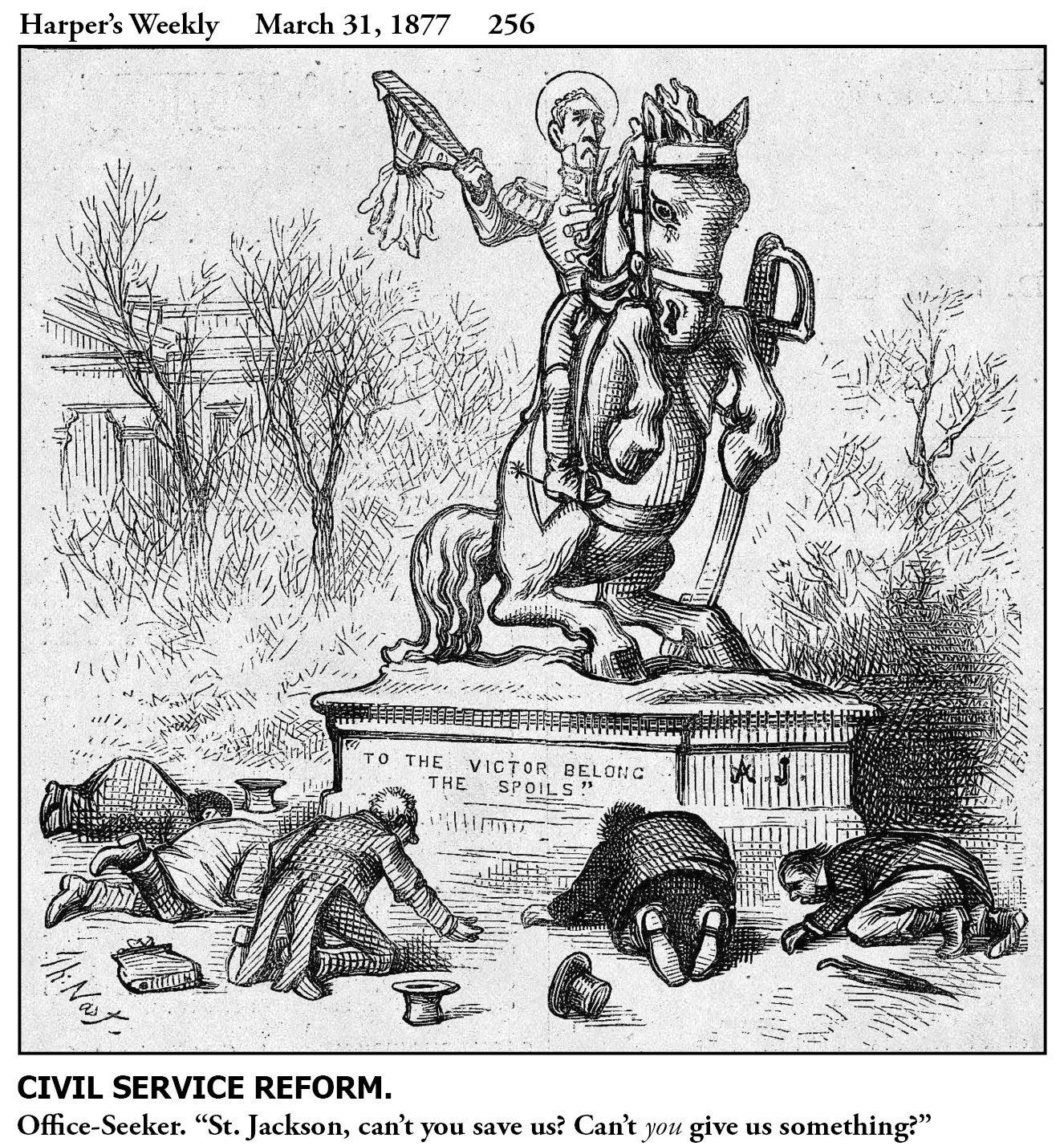

Jacksonian Era (1829-1883): The "Spoils System"

President Andrew Jackson introduced a dramatically different approach to bureaucratic appointments, based on democratic rather than elite values. Jackson criticized the notion that only the wealthy and well-educated could serve in government, arguing that ordinary citizens could perform most administrative functions. He implemented a "rotation in office" policy, replacing many existing officials with his supporters.

This approach, which critics derided as the "spoils system" (based on the saying "to the victor belong the spoils"), had several rationales:

Democratic representation: Bringing more ordinary citizens into government service would make bureaucracy more responsive to popular will.

Prevention of corruption: Regularly rotating officials would prevent them from becoming entrenched and using their positions for personal gain.

Party building: Distributing government positions to loyal supporters strengthened party organizations.

Political accountability: When a new party won an election, personnel changes throughout the bureaucracy would ensure implementation of the winning party's agenda.

The spoils system, or patronage system, democratized the bureaucracy in terms of class background (though it remained limited to white men). However, it created significant governance problems. Frequent personnel turnover prevented the development of expertise and institutional knowledge. The quality of administration suffered as appointments rewarded political loyalty rather than competence. However, many administrative tasks during this period—delivering mail, collecting customs duties—required less specialized expertise than modern regulatory functions, making the costs of personnel turnover less severe than they would be today.

Despite these drawbacks, the spoils system persisted for decades because it served important political functions, particularly strengthening party organizations. By linking government employment directly to electoral outcomes, the system created powerful incentives for citizens to participate in campaign activities. Party workers devoted countless hours to canvassing neighborhoods, organizing rallies, and getting voters to the polls—all with the understanding that their efforts might be rewarded with government positions if their candidate won.

Progressive Era to Present: Merit System and Civil Service Protection

Inefficiencies revealed during the Civil War and the assassination of President James Garfield in 1881 (by a disappointed office-seeker who was not given a patronage position) catalyzed support for civil service reform. In 1883, Congress passed the Pendleton Act, which established competitive examinations for certain federal positions and prohibited the removal of covered employees for political reasons. Initially applying to only about 10% of federal jobs, the merit system expanded over time through executive orders. Presidents would often extend civil service protection to their appointees before leaving office, preventing their successors from replacing them with political supporters.

The Progressive movement advocated for a bureaucracy based on professional expertise rather than political connections. Progressives believed that scientific management and technical knowledge could solve social problems if administrators were insulated from partisan politics. This perspective aligned with expanding government responsibilities, as industrial society created more complex regulatory challenges requiring specialized knowledge.

The New Deal dramatically expanded the federal bureaucracy, both in size and scope. President Franklin Roosevelt created numerous new agencies to address the Great Depression and established the modern civil service system. At this time, approximately 80% of federal employees worked under merit protection, fundamentally changing the relationship between politics and administration.

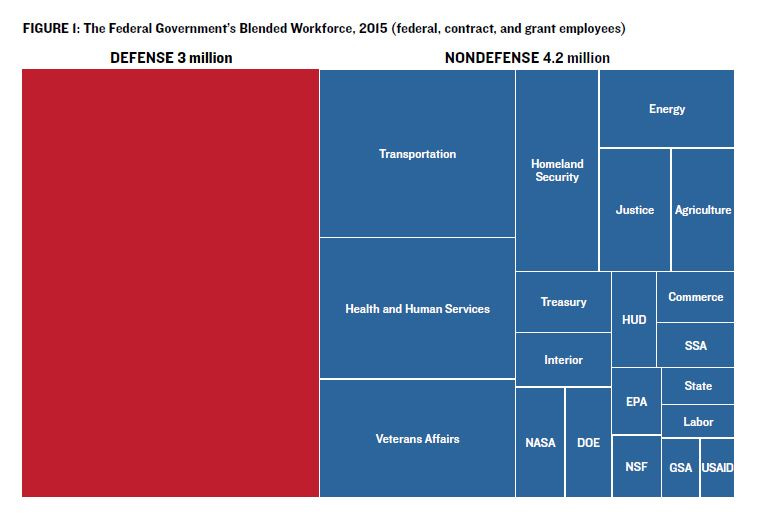

The Contemporary Bureaucracy: Structure and Functions

The modern bureaucracy consists of various types of agencies with different relationships to elected officials. Understanding this structure helps explain the complex dynamics of administrative power and accountability.

Types of Agencies

The federal bureaucracy includes several organizational forms:

Cabinet departments: Fifteen executive departments (Agriculture (USDA), Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy (DOE), Health and Human Services (HHS), Homeland Security (DHS), Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Interior (DOI), Justice (DOJ), Labor, State, Transportation (DOT), Treasury, Veteran Affairs), each led by a secretary appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. These departments contain numerous sub-agencies, bureaus, and offices—the National Park Service within Interior, for instance, or the Food and Drug Administration within Health and Human Services.

Independent executive agencies: Organizations outside cabinet departments but under presidential authority, such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Independent regulatory commissions: Agencies designed with greater independence from presidential control, often with multi-member boards serving staggered terms. Examples include the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and Federal Reserve Board (Fed). These agencies typically combine rulemaking, adjudication, and enforcement functions within their jurisdictional areas.

Government corporations: Organizations that provide commercial services, like the U.S. Postal Service.

This complex organizational landscape reflects diverse approaches to balancing political control with administrative effectiveness across different policy domains.

Types of Bureaucrats

The federal workforce includes two broad categories of employees:

Career civil servants: The vast majority of federal employees, hired through competitive examination processes or skill-based interview, rather than political appointment. These employees receive civil service protection against arbitrary dismissal and typically remain in government across multiple administrations. They range from clerical workers to high-level managers and include professionals like scientists, lawyers, economists, and analysts who provide technical expertise.

Political appointees: Approximately 4,000 positions filled by presidential appointment, including cabinet secretaries, agency heads, and their deputies. These officials serve at the president's pleasure and can be removed without cause. They provide political direction to agencies, translating the president's agenda into administrative action.

This dual structure creates inherent tensions. Career officials provide continuity and expertise but may resist changes that conflict with agency traditions or professional norms. Political appointees provide democratic accountability through their connection to the elected president but may lack substantive knowledge of their agencies' work or be excessively focused on political objectives.

Bureaucratic Powers: Rulemaking and Implementation

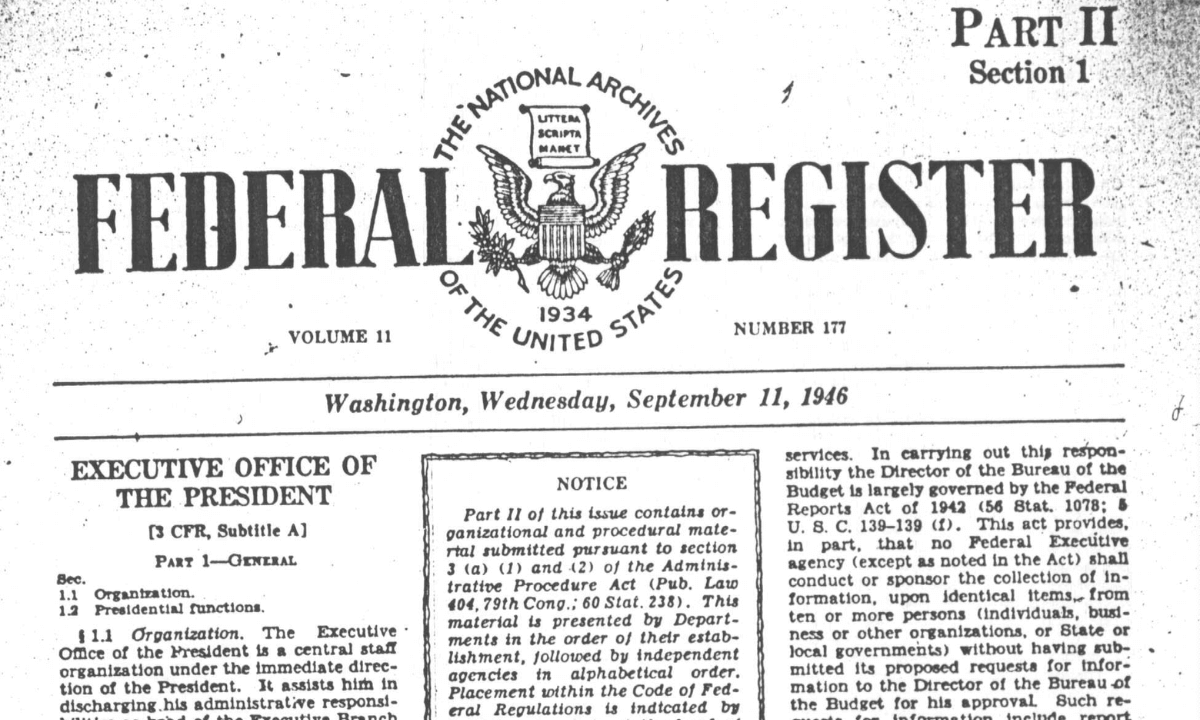

The bureaucracy's most significant power is rulemaking—translating broad legislative directives into specific, enforceable regulations. The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) of 1946 established standardized processes for agency rulemaking, including:

Notice of proposed rulemaking: Agencies must publish proposed rules in the Federal Register and invite public comment.

Comment period: Interested parties (individuals, businesses, interest groups) may submit written comments on proposed rules.

Response to comments: Agencies must consider public input and explain their reasoning in the final rule.

Publication of final rule: Completed regulations are published in the Federal Register.

This process gives agencies substantial discretion while maintaining procedural safeguards. Consider the Clean Air Act example: Congress established the general goal of reducing air pollution, but the Environmental Protection Agency determines specific emissions standards through rulemaking. These standards have the force of law, though they can be challenged in court or overridden by new legislation.

These functions give bureaucrats significant influence over how abstract policy goals translate into practical effects on citizens' lives. A law might guarantee healthcare benefits, for instance, but bureaucratic decisions about application procedures, eligibility verification, and claims processing determine how, and how easily, beneficiaries can access those benefits.

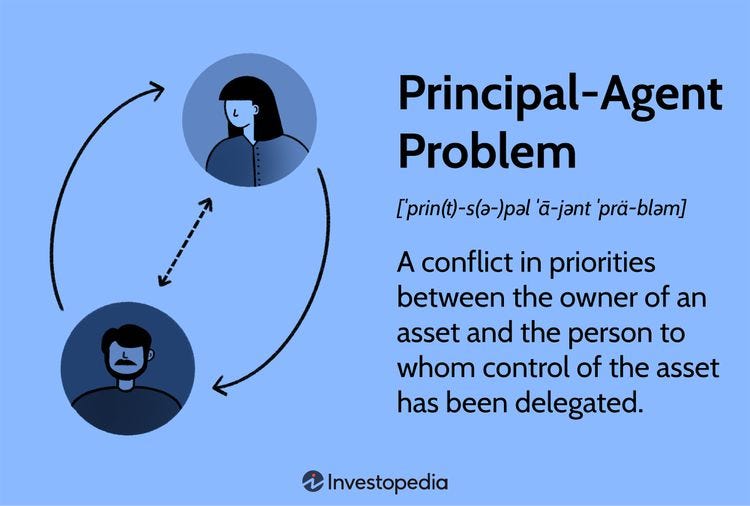

The Principal-Agent Problem in Bureaucratic Governance

The relationship between elected officials and bureaucrats exemplifies the principal-agent problem in political science. Elected officials (principals) delegate authority to bureaucrats (agents) but cannot perfectly monitor or control their actions. This creates potential for agency loss—the difference between what principals want and what agents actually do.

Several factors contribute to agency loss in bureaucratic governance:

Information asymmetry: Bureaucrats typically possess greater technical knowledge about their policy areas than elected officials, allowing them to justify decisions that align with their own preferences.

Multiple principals: Bureaucrats answer to the president, Congress, courts, and various stakeholders, creating ambiguity about whose directions should take priority.

Preference divergence: Career bureaucrats may have policy preferences that differ from current elected officials, particularly following changes in party control.

Administrative discretion: Vague statutory language often necessitates interpretation, giving bureaucrats latitude in implementation.

These dynamics help explain why presidents often express frustration with the bureaucracy's responsiveness to their directives. President Obama reportedly felt that Pentagon officials were trying to force his hand on troop deployments to Afghanistan, while President Trump frequently complained about resistance from what he termed the "deep state." Such tensions reflect the inherent challenges of controlling a complex administrative apparatus rather than necessarily indicating disloyalty or improper behavior by bureaucrats.

However, several mechanisms exist to address agency loss and enhance democratic control over bureaucratic actions.

Controlling the Bureaucracy: Mechanisms of Accountability

Each branch of government employs different strategies to influence bureaucratic behavior, creating a complex web of accountability relationships.

Congressional Control

Congress possesses several tools for directing and monitoring administrative agencies:

Statutory control: Writing detailed legislation that limits bureaucratic discretion or establishes specific requirements for implementation.

Budgetary power: Appropriating (or withholding) funds to shape agency behavior.

Oversight hearings: Calling agency officials to testify about their activities and decisions.

Confirmation authority: Reviewing and approving (or rejecting) presidential nominees for senior agency positions.

Investigations: Conducting inquiries into alleged misconduct or policy failures.

Political scientists McCubbins and Schwartz distinguish between two oversight strategies: police patrols and fire alarms.

Police patrol oversight involves regular, proactive monitoring through hearings, studies, and direct observation—resource-intensive activities that legislators have limited capacity to perform.

Fire alarm oversight establishes procedures for affected parties (citizens, interest groups, media) to "sound the alarm" when agencies deviate from congressional intent, allowing more efficient targeting of oversight resources.

Given constraints on their time and resources, Congress typically relies on fire alarm oversight, allowing interested parties to flag problems that Congress can then investigate.

Congress has created various institutions to assist with oversight, including:

Inspectors General: Independent officials within agencies who audit operations and investigate misconduct.

Government Accountability Office: Congressional agency that evaluates program effectiveness and efficiency.

Congressional Research Service: Provides objective policy analysis to inform legislative decisions.

Despite these mechanisms, congressional overseers are limited in their ability to monitor the bureaucracy. Partisan polarization reduces incentives for the president's co-partisans in Congress to scrutinize executive branch actions, while the opposition party may focus more on generating political controversies than improving administrative performance. Additionally, the complexity and volume of bureaucratic activities make comprehensive oversight practically impossible.

Presidential Control

Presidents, as nominal heads of the executive branch, employ various strategies to direct bureaucratic behavior:

Appointment power: Selecting agency leaders who share the president's policy preferences and will work to implement the administration's agenda.

Removal authority: Dismissing appointees who fail to align with presidential priorities (though this power is limited for some independent agencies).

Executive orders: Issuing directives that establish priorities and procedures for executive branch activities.

Budgetary proposals: Requesting funding allocations that reflect presidential priorities.

Centralized review: Using the Office of Management and Budget to evaluate proposed regulations before publication.

Presidential influence has grown through organizational innovations like the expansion of White House staff and creation of the Executive Office of the President. These institutions enhance the president's capacity to monitor and direct administrative activities across the executive branch.

However, presidents face constraints in exercising control over the bureaucracy. Most notably, civil service protections limit presidents' ability to remove career officials whose policy preferences differ from their own. This limitation, established to prevent a return to the spoils system and protect expertise, frustrates presidents seeking to quickly reorient administrative action after taking office.

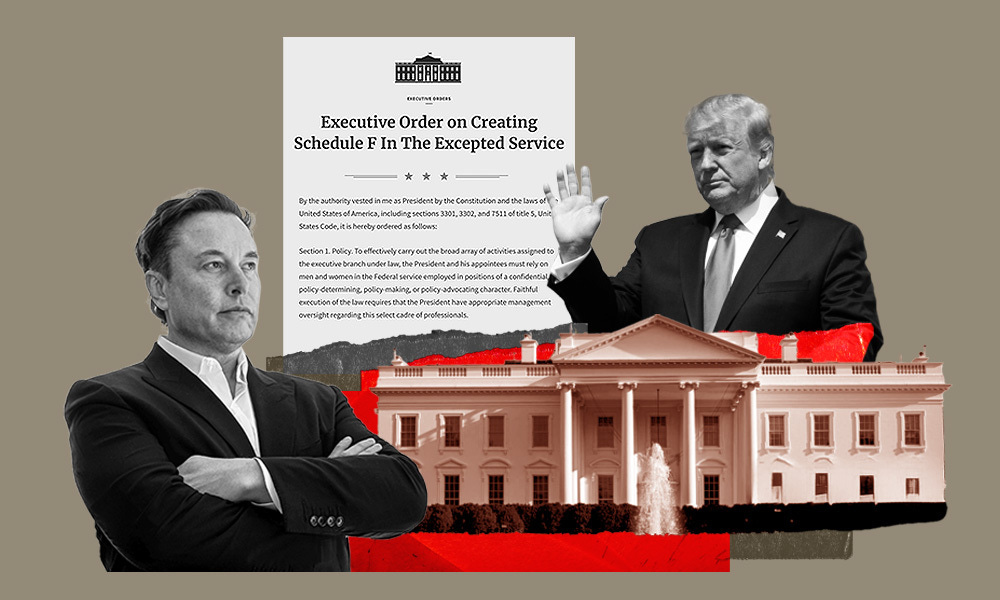

In his first term, President Trump's "Schedule F" executive order attempted to expand presidential control by reclassifying many civil service positions as policy-related, making their occupants subject to removal without cause. Though later rescinded by President Biden, this initiative highlighted ongoing tensions between presidential authority and bureaucratic autonomy. The executive order's return with the second Trump administration will test constitutional boundaries regarding the balance between political responsiveness and administrative expertise.

Judicial Control

Courts provide another check on bureaucratic action, primarily through judicial review of agency decisions. Under the Administrative Procedure Act, courts can invalidate agency actions that are:

Arbitrary and capricious: Lacking reasonable basis or adequate explanation.

Contrary to law: Inconsistent with the agency's statutory authority.

Procedurally defective: Failing to follow required processes for decision-making.

Judicial oversight forces agencies to justify their decisions with evidence and reasoned analysis. For example, courts blocked the Trump administration's attempt to rescind the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program not because the administration lacked authority to end the program, but because it failed to provide adequate justification and follow proper procedures under the APA.

For decades, "Chevron Deference" (established in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, 1984) instructed courts to defer to agencies' reasonable interpretations of ambiguous statutory provisions, recognizing agencies' greater expertise and political accountability compared to judges. However, in a landmark 2024 decision, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the Supreme Court overturned this precedent, asserting greater judicial authority to interpret statutory language without deferring to agency interpretations. This shift strengthens judicial control over bureaucratic action at the expense of both presidential and agency authority.

The Bureaucracy and Democratic Governance: Persistent Tensions

Public approval of the federal government remains consistently low, with bureaucracy often portrayed as inefficient, unresponsive, and unaccountable. Yet paradoxically, Americans typically support the specific programs that bureaucratic agencies administer—from national parks to medical research to air traffic control.

This contradiction reflects broader tensions inherent in bureaucratic governance:

Expertise vs. Democratic Control

Modern governance requires specialized knowledge that most citizens and elected officials lack. Technical decisions about food safety standards, environmental regulations, or financial oversight necessarily rely on professional expertise. Insulating bureaucrats from political pressure allows them to make decisions based on evidence and professional standards rather than partisan considerations.

However, this insulation can undermine democratic accountability when bureaucratic priorities diverge from public preferences. Technical expertise, while essential, doesn't resolve value judgments about trade-offs between competing goals—such as economic growth versus environmental protection. In a democracy, such value judgments should ultimately reflect citizens' preferences expressed through elected representatives, not bureaucrats' personal views.

Stability vs. Responsiveness

Career civil servants provide continuity and institutional memory across administrations, preventing policy whiplash and maintaining operational effectiveness during transitions. This stability serves democratic governance by ensuring that government functions reliably despite electoral volatility.

Yet stability can become rigidity when bureaucrats resist implementing new directions after elections produce changes in leadership. If administrative practices remain unchanged despite shifts in voter preferences, the principle of democratic accountability suffers. The challenge lies in distinguishing principled professional judgment from bureaucratic obstruction of legitimate policy changes.

Efficiency vs. Procedural Safeguards

Procedural requirements for bureaucratic action—public notice, comment periods, evidence-based justification—protect against arbitrary decisions and enhance democratic legitimacy. However, these same procedures can delay action and increase administrative costs, creating inefficiencies that frustrate both officials and citizens.

Streamlining procedures might improve bureaucratic responsiveness but could also reduce opportunities for public input and careful deliberation. This tension between procedural thoroughness and administrative efficiency represents another fundamental trade-off in bureaucratic governance.

Conclusion: Unearthing the "Deep State" Narrative

The provocative term "deep state" obscures more than it illuminates about American bureaucracy. Rather than a monolithic entity pursuing its own agenda, the federal bureaucracy consists of diverse agencies with different cultures, missions, and relationships to elected officials. Career civil servants generally strive to implement laws effectively while navigating competing demands from presidents, Congress, courts, and the public.

The bureaucracy's size and complexity certainly create challenges for democratic accountability. Presidents of both parties have expressed frustration when administrative actions don't align with their preferences. However, these tensions result primarily from institutional structures deliberately designed to balance competing values—expertise and democratic control, stability and responsiveness, efficiency and procedural fairness.

Rather than viewing bureaucracy as inherently opposed to democracy, we should recognize it as an inevitable component of modern democratic governance. The relevant question isn't whether bureaucracy should exist—complex societies require administrative capacity—but how bureaucratic power should be structured and constrained to serve democratic principles.

Efforts to reform the bureaucracy typically reflect particular positions regarding these underlying tensions. Those emphasizing democratic control advocate for strengthening presidential authority over agencies, expanding political appointments, or reducing civil service protections. Those prioritizing expertise and administrative effectiveness support greater bureaucratic autonomy, stronger merit protections, and insulation from political interference.

In the end, bureaucracy reminds us that democracy involves more than electoral competition—it requires institutional arrangements that translate popular preferences into effective governance. The constitutional system of separated powers and checks and balances extends to administrative agencies, creating a bureaucracy that is neither fully autonomous nor completely controlled by any single elected official. This complex balance frustrates presidents and citizens alike but also prevents concentration of power that could threaten democratic governance itself.

Key Terms

Administrative Procedure Act (APA): Federal law establishing requirements for agency rulemaking and providing for judicial review of agency actions.

Agency loss: The difference between what principals (elected officials) want and what agents (bureaucrats) actually do.

Chevron Deference: Former judicial precedent instructing courts to defer to reasonable agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes.

Civil service: Employment system based on merit rather than political appointment, with protections against arbitrary dismissal.

Delegation: The transfer of policymaking authority from Congress to administrative agencies.

Fire alarm oversight: Congressional oversight strategy that relies on affected parties to report problems with agency performance.

Merit system: Hiring and promotion based on qualifications and performance rather than political connections.

Police patrol oversight: Proactive congressional monitoring of agency activities through hearings, studies, and direct observation.

Political appointees: Officials selected by the president (often with Senate confirmation) who serve at the president's pleasure.

Rulemaking: Process through which agencies develop specific regulations to implement broader legislative directives.

Schedule F: Executive order attempting to reclassify many civil service positions as policy-related, making occupants subject to removal without cause.

Spoils system: Practice of distributing government positions to supporters of the winning political party.