More Presidential Power, More Presidential Problems

Power, constraint, and leadership in a polarized age.

Learning Objectives

Understand the multiple representational roles of the modern presidency.

Analyze the constitutional design of the presidency and its evolution over time.

Identify the formal and informal powers presidents use to advance their agendas.

Evaluate how partisan polarization has transformed presidential leadership.

Explain how institutional constraints limit presidential power despite public expectations.

Introduction: The Paradox of Presidential Power

"Who does the president represent?" This seemingly straightforward question reveals a fundamental tension at the heart of the American presidency. Unlike members of Congress, who represent specific geographic constituencies, presidents face competing representational demands. They must simultaneously serve as the symbolic head of the entire nation, the leader of their political party, the commander in chief of the military, and a caring figure in the wake of national tragedy, among other things.

Modern presidents operate in a political environment vastly different from what the Constitution's framers envisioned. Today's presidents are expected to solve national problems, lead legislative initiatives, manage economic prosperity, ensure national security, and respond to crises both domestic and international. Yet the formal constitutional powers granted to the president are remarkably limited. This creates what scholars call the “expectation gap”—the difference between what citizens expect presidents to accomplish and the institutional tools presidents actually possess to meet these expectations.

The presidency exemplifies a key concept we've encountered previously: path dependence. The office has evolved dramatically from its constitutional origins, but always within parameters established by earlier institutional choices. By examining how the presidency has developed over time—from its modest beginnings to its current prominence—we can better understand both the possibilities and limitations of presidential leadership in contemporary American politics.

Constitutional Design: Energy and Safety

The Framers' Vision

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention approached the creation of the executive branch with considerable caution. Having just fought a revolutionary war against King George III's monarchy, they were wary of establishing another powerful executive who might threaten republican governance. Yet they also recognized the failures of the Articles of Confederation, which lacked any central executive authority and therefore struggled with collective action problems during the Revolutionary War.

Alexander Hamilton articulated this delicate balance in Federalist No. 70, arguing that an effective executive required "energy," which derived from "unity; duration; an adequate provision for its support; competent powers." At the same time, republican "safety" demanded "a due dependence on the people; a due responsibility." Hamilton and the other Federalists sought a presidency powerful enough to act decisively yet constrained enough to prevent tyranny.

The resulting constitutional design created an office with significant but carefully circumscribed powers. Article II of the Constitution is notably brief compared to Article I's extensive treatment of Congress, reflecting the Framers' expectation that Congress would remain the dominant branch as well as disagreements over what powers the president should have.

The president received specific enumerated powers, most of which required coordination with other branches:

Commander in Chief of the armed forces, but dependent on congressional declaration of war.

Appointment power for executive officers and judges, subject to Senate confirmation.

Treaty power to negotiate international agreements, requiring two-thirds Senate approval.

Veto power over legislation, which Congress has passed and that Congress can override with a two-thirds vote.

State of the Union authority to recommend measures to Congress (but no formal power to introduce legislation).

Calling Congress into special session, but today Congress is always in session.

Pardon power, which is one of the few unilateral presidential powers.

The Constitution also created a unique method for selecting the president: the Electoral College. This system reflected the delicate balance of the Great Compromise, giving states a defined role in presidential selection while establishing a mechanism separate from both direct popular election and congressional appointment. The Electoral College allocates electoral votes to states based on their congressional representation (House plus Senate seats), which gives smaller states disproportionate influence while still acknowledging population differences.

As Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist No. 68, the Electoral College was designed to ensure "that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications." The Framers expected electors to exercise independent judgment rather than simply transmitting popular preferences. This original vision has evolved significantly through practice, with most states now allocating their electoral votes to the statewide popular vote winner, creating a "winner-take-all" system within states.

The Modest Presidency of the Nineteenth Century

For much of the nineteenth century, the presidency largely conformed to the modest role the Framers had envisioned. Congress dominated national policymaking, while presidents focused primarily on executing existing laws and distributing federal patronage—appointing supporters to government positions like postmasters. Nineteenth-century presidents were expected to be "clerks" rather than leaders, managing the administrative apparatus without significantly shaping policy. As political scientists Jacobson and Kernell (1987) wrote of nineteenth-century presidents:

“Presidents were selected to head the national ticket according to their electability and willingness to distribute the spoils fairly among the many state organizations. Their role was to provide a rallying point for the hundreds of state and local party organizations around the country, and an appealing choice to voters. Candidates who were associated with divisive issues or the party politics of a particular region were unattractive. Consequently, men with little experience in government and political parties held an advantage. Appropriately, with election to the White House, their function ended.”

The cabinet played a more prominent role in this era than it does today. Presidents regularly deferred to cabinet secretaries on policy matters within their departments, creating a principal-agent problem. Cabinet secretaries often pursued their own agendas, sometimes at odds with presidential preferences, leading presidents to gradually centralize more authority within the White House itself.

This limited presidency aligned with the relatively small federal government of the era. Before the twentieth century, the national government had few permanent administrative agencies and limited regulatory responsibilities. Most governance occurred at the state and local levels, with the president overseeing a modest federal apparatus focused largely on postal services, customs collection, military affairs, and foreign relations.

The Modern Presidency: From Roosevelt to Reagan

The Roosevelt Revolution

The modern presidency emerged in response to national crises that demanded stronger executive leadership. The transformative presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945) fundamentally redefined the office in response to the Great Depression and World War II. As political scientist Sidney Milkis observes, Roosevelt created a "modern presidency" that established the White House as the center of national policymaking and popular leadership.

Several factors contributed to this transformation:

The Great Depression required unprecedented federal intervention, with the president taking the lead in proposing New Deal legislation.

World War II dramatically expanded presidential authority as commander-in-chief and diplomatic leader.

New communications technologies, particularly radio, and then television, enabled presidents to speak directly to the public.

Growth of the administrative state increased the executive branch's policymaking capacity.

Public expectations shifted toward seeing the president as the primary representative of national interests.

Roosevelt pioneered what would become defining features of the modern presidency: proposing comprehensive legislative programs, using mass media to mobilize public support, and building a robust White House staff to coordinate policy across the expanding executive branch. Perhaps most importantly, he established the expectation that presidents would take primary responsibility for the nation's economic welfare and security—a responsibility far beyond what earlier presidents had assumed (or even believed was legal).

The constitutional basis for this expanded presidency often derived from creative interpretations of Article II, particularly the Take Care Clause ("The President shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed") and the Vesting Clause ("The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America"). These provisions, interpreted broadly, allowed presidents to claim substantial discretion in implementing laws and managing the executive branch.

The President as Legislative Leader

Modern presidents have become de facto legislative leaders despite having no formal constitutional power to introduce bills. Presidents campaign on policy platforms, propose detailed legislative agendas upon taking office, and are held politically accountable for legislative outcomes. This transformation lead political scientist Richard Neustadt to call presidential power the "power to persuade." Since the president cannot force anyone to do anything, she must convince others that their interests align with hers.

The public increasingly expects presidents to deliver policy solutions to national problems, from healthcare reform to economic growth to climate change. This expectation persists despite the constitutional separation that gives Congress, not the president, primary lawmaking authority.

Even without formal power, presidents possess several tools for influencing the legislative process:

Setting the agenda through State of the Union addresses, budget proposals, and other public statements.

Building congressional coalitions through personal relationships, partisan appeals, and interest group mobilization.

Going public by appealing directly to citizens through speeches and media appearances.

Threatening vetoes to shape legislation before it reaches the president's desk.

Using appointment power to staff the executive branch with officials who share the president's policy priorities.

These informal powers allow presidents to influence legislation despite their limited formal authority. Public expectations, partisan dynamics, and media coverage all reinforce the president's centrality in the legislative process.

Patterns of Presidential Support in Congress: Unified vs. Divided Government

The effectiveness of presidential legislative leadership depends heavily on partisan control of Congress. This institutional context shapes both the president's strategic options and congressional responsiveness to presidential initiatives.

Unified Government

Under unified government—when the president's party controls both chambers of Congress—presidents can generally expect greater legislative success. Several factors contribute to this advantage:

Ideological alignment: The president and congressional majority typically share broad policy goals and priorities.

Partisan loyalty: Co-partisans in Congress have electoral incentives to support a successful president from their party.

Procedural advantages: The president's party controls committee chairmanships, scheduling, and other procedural levers that facilitate passage of presidential priorities.

Reduced veto barriers: Legislation can be crafted with presidential input, reducing the likelihood of vetoes.

Historically, presidents have achieved their most significant legislative accomplishments during periods of unified government. Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, Lyndon Johnson's Great Society programs, and Barack Obama's Affordable Care Act all passed during periods when their party controlled both chambers of Congress. These examples demonstrate how unified government creates opportunities for major policy change aligned with presidential priorities.

However, unified government does not guarantee legislative success. Intra-party divisions, especially in a diverse party coalition, can complicate presidential leadership even when the president's party holds majorities in both chambers. President Carter, for instance, struggled to advance his energy agenda despite Democratic majorities in Congress, largely due to ideological divisions within the Democratic Party in the late 1970s.

Divided Government

Under divided government—when at least one chamber of Congress is controlled by the opposition party—presidential legislative influence diminishes substantially. Opposition parties have both policy disagreements with the president and strategic incentives to deny the president legislative victories. As Republican Senate Leader Mitch McConnell bluntly stated in 2010, "The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president." This strategic opposition reflects the reality that presidential success often translates into electoral advantages for the president's party.

Divided government creates several obstacles to presidential leadership:

Ideological distance: The opposition party often fundamentally disagrees with the president's policy preferences.

Electoral incentives: The opposition party benefits electorally from presidential failures.

Procedural barriers: The opposition can use committee control and scheduling power to block presidential initiatives.

Veto politics: Legislation may be crafted specifically to force presidential vetoes that can be used against the president politically.

These dynamics help explain why divided government has become increasingly associated with legislative gridlock. As political parties have become more ideologically cohesive and polarized, finding common ground across party lines has become more difficult. The frequency of major legislative accomplishments declines significantly during periods of divided government, particularly in recent decades.

Changing Patterns of Presidential Support

Patterns of congressional support for presidents have changed dramatically over time. In the mid-twentieth century, presidents often received substantial support from members of both parties, reflecting the ideological diversity within each party at that time. Southern Democrats often voted with Republicans on certain issues, while moderate Republicans sometimes aligned with Northern Democrats on others.

Since the 1980s, however, presidential support in Congress has increasingly polarized along partisan lines. Analysis of presidential support scores—the percentage of times members of Congress vote in accordance with the president's position—reveals a widening partisan gap. Presidents now receive overwhelming support from their co-partisans in Congress and minimal support from the opposition party. This pattern holds regardless of which party controls the White House, reflecting the broader polarization of American politics. The consequence is that presidential legislative success increasingly depends on unified government, as prospects for significant bipartisan cooperation have diminished substantially.

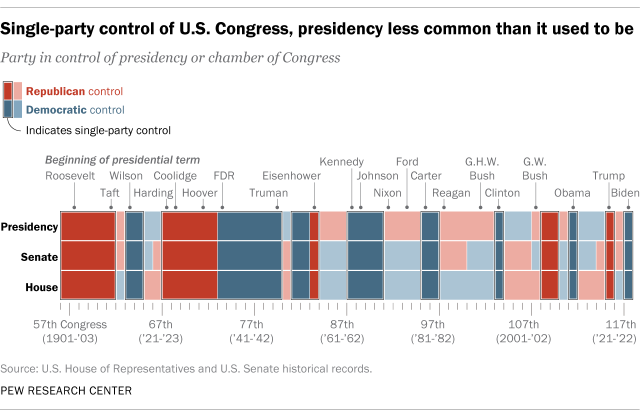

The historical pattern of divided government reveals significant changes in presidential-congressional relationships over time. Prior to the 1940s, presidents could almost always count on unified government during their tenure in office, allowing for greater policy coordination between the branches. This pattern shifted dramatically in the post-war era, when Democrats took control of Congress and held huge majorities until the 1980s. Republican presidents Eisenhower, Nixon, and Ford all governed with Democratic Congresses, creating a stable pattern of divided government with relatively moderate levels of partisan conflict.

Republican victories in the 1980 Senate elections and the 1994 House elections ushered in a period of much narrower congressional majorities and more frequent changes in chamber control. This new era has produced a predictable cycle: presidents routinely begin their term with unified government, only to lose it in the midterm elections when voters often turn against the president's party. This pattern further complicates presidential efforts to sustain legislative momentum throughout their time in office.

The Strategy of Going Public

One response to legislative gridlock has been what political scientist Samuel Kernell calls "going public"—presidents' efforts to mobilize public opinion through speeches, travel, and media appearances. This strategy aims to pressure legislators by demonstrating popular support for presidential initiatives. If presidents can persuade the public to support their objectives, then legislators may support the president in response to their constituents’ demands. Modern communication technologies, from television to social media, have expanded presidents' ability to communicate directly with citizens, potentially bypassing traditional media gatekeepers.

However, research suggests that going public has become less effective in a polarized era. Political scientist Frances Lee has demonstrated that presidential involvement in an issue often increases partisan polarization rather than building consensus. When presidents publicly advocate for policies, members of the opposition party become more likely to oppose those policies, while co-partisans become more supportive. As a result, presidential rhetoric may actually reduce the prospects for bipartisan cooperation on contentious issues.

The effectiveness of going public is further limited by partisan polarization among voters. The gap in presidential approval ratings between voters of different parties has widened dramatically over time. Where Eisenhower (R) benefitted from over 50% approval among Democratic voters, during the Obama administration, there was nearly a 70-point gap between how Democrats and Republicans evaluated the president's performance—a pattern that has continued under Presidents Trump and Biden. This polarization means that presidential appeals rarely persuade citizens who identify with the opposition party, limiting the president's ability to build broad public pressure for their agenda.

Presidential Vetoes and Veto Threats

Among the president's formal legislative powers, the veto stands out as particularly consequential. The Constitution grants presidents the authority to reject legislation passed by Congress, forcing a two-thirds vote in both chambers to override the presidential veto. This supermajority requirement makes the veto a powerful tool, as assembling a two-thirds coalition in both chambers is exceedingly difficult in a polarized environment.

Presidents use this authority in several ways:

Actual vetoes: Formally rejecting legislation that has passed both chambers of Congress. These are relatively rare but send strong signals about presidential priorities.

Veto threats: Public statements (e.g., in public statements or press conferences) or written documents (e.g., in Statements of Administration Policy) indicating the president will veto legislation unless certain conditions are met. These threats are often issued by the White House as bills move through Congress.

Veto threats serve as a form of anticipatory influence, shaping legislation before it reaches the president's desk. When Congress believes the president will veto a bill and doubts its ability to override that veto, it often modifies the legislation preemptively to secure presidential approval. Thus, even if a president never formally uses their veto, its existence (and the possibility that the president could use it) can still affect legislative outcomes.

The frequency of both veto threats and actual vetoes correlates strongly with divided government. When the opposition party controls Congress, presidents issue more veto threats and cast more vetoes, using this negative power to defend their priorities against hostile legislation. Under unified government, presidents rarely need to threaten vetoes, as their co-partisans in Congress generally avoid sending unacceptable legislation to the White House. Notice, in the figure below, how both vetoes and veto threats increase when the presidency and Congress are controlled by different parties and decreases during periods of same-party control.

The veto illustrates an important asymmetry in presidential power: it is primarily a negative rather than positive tool. Presidents can more easily block policies they oppose than enact policies they favor. This defensive capability becomes particularly important during periods of divided government, when presidents have limited ability to advance their affirmative agendas through Congress.

Unilateral Powers and Executive Actions

As legislative pathways have become more challenging, presidents have increasingly turned to unilateral tools to advance their agendas. Modern presidents use executive orders, presidential memoranda, proclamations, and other directives to shape policy without congressional action. These tools rely on presidents' authority to interpret and implement existing laws, often finding discretionary space that allows them to pursue their policy preferences within statutory boundaries.

The president's role in interpreting laws derives from multiple constitutional and statutory sources. The Constitution's “Take Care Clause” (Article II, Section 3) requires that the president "take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed," making the president responsible for implementing legislation passed by Congress. This implementation necessarily involves interpretation, as laws rarely specify every detail of their execution. Congress often leaves laws somewhat vague to allow them to be flexible as conditions change and/or because lawmakers cannot always agree on specific language.

The Vesting Clause (Article II, Section 1), which states that "The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America," has also been interpreted by presidents and some legal scholars as providing inherent executive authority beyond specific enumerated powers. This "unitary executive" theory, particularly prominent during the Reagan, George W. Bush, and Trump administrations, holds that presidents possess substantial discretion in how they execute the law.

Key examples of consequential unilateral actions include:

President Obama's creation of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program in 2012, which allowed certain undocumented immigrants brought to the United States as children to remain in the country without fear of deportation.

President Trump's implementation of travel restrictions on individuals from several majority-Muslim countries in 2017.

President Trump’s recent executive order attempting to eliminate birthright citizenship.

Various presidents' use of executive orders to regulate environmental protection, labor practices, and other policy areas.

These unilateral powers face important limitations:

Statutory constraints: Presidents can only act within authority already delegated by Congress in existing laws. Presidents cannot create entirely new programs or regulatory frameworks without some basis in existing law.

Durability problems: Future presidents can easily rescind their predecessors' executive actions, making unilateral accomplishments potentially temporary. Anything one president can do unilaterally, another president can undo unilaterally.

Congressional override: Congress can pass new legislation that specifically prohibits presidential actions, though these laws remain subject to presidential veto.

Judicial review: Courts can invalidate executive actions that exceed statutory authority or violate constitutional provisions.

Political scientists Terry Moe and William Howell found that between 1973 and 1997, Congress attempted to overturn executive orders 37 times but succeeded only 3 times, highlighting the difficulty of reversing presidential unilateralism through legislation. However, court challenges have become increasingly common and sometimes successful in constraining presidential actions.

Contemporary Challenges: Representation in a Polarized Era

Multiple Representative Roles

Who do presidents represent? Modern presidents navigate multiple, sometimes conflicting, representational roles. Political scientists have identified at least three distinct ways presidents represent their constituents:

National representation: Presidents represent the entire nation as one of the only elected officials with a national constituency. Presidents often invoke this role when claiming to speak for broader national interests beyond partisan politics.

Partisan representation: Presidents represent their political parties and the voters who elected them. As presidents increasingly depend on co-partisans for electoral support, they may feel they only need to respond to voters most likely to re-elect them.

Strategic representation: Presidents may give special attention to key constituencies whose support is crucial for reelection. Given the Electoral College system, this often means focusing particularly on voters in competitive "swing states" rather than distributing attention equally across all states.

These competing representative roles create tensions in presidential leadership. Should presidents prioritize policies that appeal to the broader nation, focus on delivering for their partisan base, or target benefits to strategically important constituencies? Different presidents resolve these tensions differently, but the increasingly polarized political environment often pushes presidents toward partisan representation, as the prospects for winning over opposition voters diminish.

The Expectation Gap and the "Green Lantern" Theory

Despite the institutional constraints presidents face, public expectations for presidential leadership remain extremely high. Citizens often hold presidents personally responsible for economic conditions, legislative outcomes, and national well-being, even when presidents have limited control over these factors. Political scientist Brendan Nyhan calls this the "Green Lantern theory of the presidency"—the belief that presidents can overcome any obstacle through sufficient will, effort, or persuasive skill.

This expectation gap reflects several factors:

Presidential campaigns encourage candidates to make expansive promises about what they will accomplish if elected.

Media coverage focuses disproportionately on the president as the central political actor.

The symbolic aspects of the presidency, including its ceremonial functions, reinforce the image of presidential power.

Americans' limited knowledge of constitutional constraints leads to unrealistic expectations about presidential authority.

In a recent study, the political scientist Scott Clifford and co-authors conducted a study in which they surveyed the public and political experts about presidential power and influence. They asked people whether they agreed with statements like “Gridlock in Congress is typically the result of a failure of presidential leadership” and “Presidents can get members of Congress of their own party to pass major legislation if they try hard enough.” As shown in the figure below, the public believes that presidents have much more power (farther to the right, higher scores on average) than political experts.

The reality is that even historically successful presidencies often depended more on favorable political contexts than on exceptional leadership skills. Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson achieved landmark legislative accomplishments in large part because they enjoyed overwhelming Democratic majorities in Congress. Their success reflected not just their personal abilities but also the partisan and institutional environments in which they operated.

This gap between expectations and institutional reality creates persistent frustration with presidential performance. Presidents are expected to solve problems they lack the formal authority to address independently, leading to cycles of hope followed by disappointment. This pattern contributes to declining trust in government and democratic institutions more broadly.

Conclusion: Presidential Leadership in Constitutional Context

The American presidency embodies fundamental tensions in democratic governance. The office must be powerful enough to provide effective leadership yet constrained enough to prevent authoritarian tendencies. Presidents must represent the entire nation while inevitably reflecting partisan perspectives. They must take responsibility for national outcomes despite having limited institutional capacity to control those outcomes.

These tensions have only intensified in an era of partisan polarization and divided government. The constitutional system of separated powers, designed to prevent tyranny through checks and balances, now often produces gridlock that frustrates citizens across the political spectrum. Presidents face ever-mounting expectations to overcome these institutional obstacles, even as polarization makes compromise more difficult. Recent presidencies have increasingly pushed the boundaries of executive authority. Presidents from both parties have expanded unilateral action, sometimes circumventing Congress entirely rather than seeking compromise.

This adaptive capacity suggests that the presidency will continue to transform in response to new challenges. As political polarization intensifies and traditional norms of presidential restraint erode, the formal and informal constraints on presidential power face unprecedented stress. The presidency's evolution reflects not just changing historical circumstances but also fundamental choices about American democratic governance.

Key Terms

Unified government: When the presidency and both chambers of Congress are controlled by the same political party.

Divided government: When the presidency and at least one chamber of Congress are controlled by different political parties.

Going public: Presidential strategy of appealing directly to citizens through speeches and media appearances to pressure Congress.

Take Care Clause: Constitutional provision requiring that the president "take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed."

Vesting Clause: Constitutional provision stating that "The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America."

Executive order: A directive issued by the president to manage operations of the federal government.

Veto power: Presidential authority to reject legislation passed by Congress, which can be overridden by a two-thirds vote in both chambers.

Green Lantern theory: The belief that presidents can overcome any obstacle through sufficient will, effort, or persuasive skill.