The Constitution Didn’t Fall Out of a Coconut Tree

How America's revolutionary constitution still shapes modern politics.

Learning Objectives

Understand the concept of path dependence and its role in shaping American political institutions.

Analyze how the Articles of Confederation influenced the creation of the Constitution.

Identify the key compromises that shaped the constitutional framework.

Evaluate how the Constitution structures the three branches of government.

Explain how the Constitution attempts to solve collective action problems.

Introduction: How We Got Here Matters

The United States Constitution didn't simply appear fully formed—it emerged from careful deliberation about the proper role of government in a republic. As political scientist Theodore Lowi and his colleagues write: "How we got here matters." The American government didn't just "fall out of a coconut tree." Rather, it evolved through complex historical processes that continue to shape political behavior and institutional functioning today.

This concept—that current political structures are shaped by historical decisions, even those made centuries ago—is what political scientists call path dependence. Although the framers of the Constitution could not anticipate our present circumstances, their choices nearly 250 years ago continue to influence American government and politics in profound ways. Understanding these historical roots helps explain why certain features of our political system persist despite criticisms and calls for reform.

Path dependence is the idea that “how we got here matters.” That current institutions and and political structures are inextricably linked to choices made in the past.

Consider some contemporary reform proposals: Supreme Court term limits, expanding the Senate to better reflect population, or eliminating the Electoral College. Despite polls showing public support for such changes, constitutional reform remains exceedingly difficult. Since the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments—only seventeen additional amendments have been ratified in more than two centuries. This remarkable stability raises important questions: Were the Framers especially prescient in designing an enduring system? Or does the Constitution's resistance to change reflect structural barriers that make reform difficult regardless of popular sentiment?

By examining the historical context of the Constitution's creation—including the experience with the Articles of Confederation—we can better understand both the enduring principles and ongoing tensions in American governance.

From British Colonies to Independent States

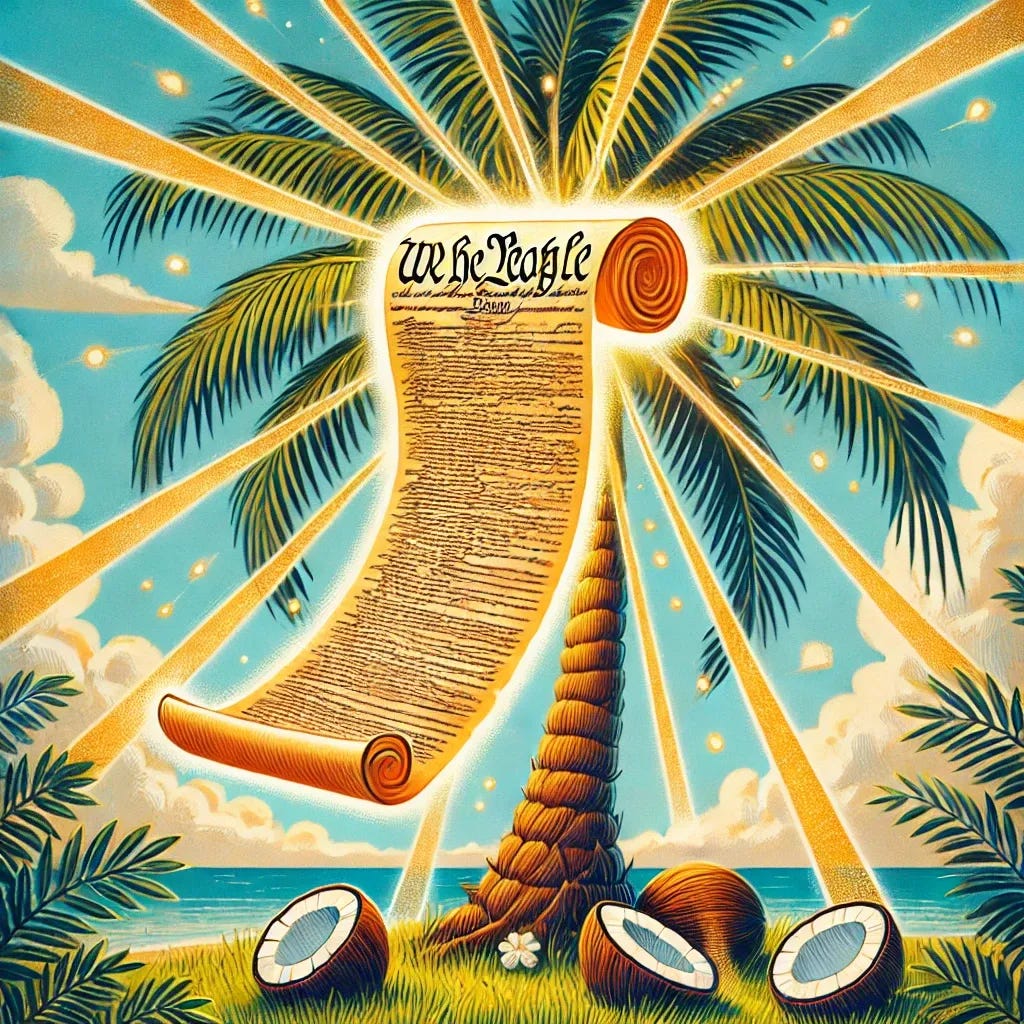

Prior to the American Revolution, the thirteen British colonies in North America operated largely independently from one another while remaining under British authority. Though subject to British rule, colonists managed many of their own affairs, with the British taking a relatively light administrative touch in many areas. This arrangement had two crucial consequences: the colonists developed experience with self-governance, but they had little experience with collective action across colonial boundaries.

This lack of coordination was so problematic that in 1754, Benjamin Franklin created what is considered America's first political cartoon. The image depicted a snake cut into pieces, with each segment representing a colony and the caption "Join, or Die." The message was clear: without coordination, the colonies would remain weak and vulnerable. This illustrated a classic collective action problem that would persist through the revolutionary period.

When the American Revolution began, the need for coordinated governance became urgent. The Continental Congress, formed to coordinate resistance to British policies, recognized that a formal governmental structure was necessary. This led to the Articles of Confederation, America's first constitution, adopted in 1777 and ratified in 1781.

The Articles of Confederation: A Failed Experiment

The Articles of Confederation attempted to replicate aspects of the colonists' previous relationship with Britain: states remained largely independent with limited federal authority. Key features of this governmental structure included:

State sovereignty: Authority derived from states rather than citizens directly.

Equal representation: Each state had one vote in Congress regardless of population.

Supermajority requirements: New laws required agreement from 9 of 13 states, while taxation changes and amendments required unanimous consent.

Limited federal power: No independent executive or judicial branch existed.

No taxation authority: The national government could request but not require financial contributions from states.

In many ways, the government under the Articles resembled today's United Nations—a coordinating body with limited enforcement powers that relied on voluntary compliance from sovereign members.

After the war, problems intensified. Congress could not pay off war debts because it lacked taxation power and states refused to contribute voluntarily. Interstate commerce was complicated by varying state regulations and tariffs. Foreign nations negotiated separately with individual states rather than with a unified American government. By 1786, these weaknesses had become so apparent that calls for reform grew increasingly urgent.

The breaking point came with Shays' Rebellion in 1786-1787, when Massachusetts farmers, many of them Revolutionary War veterans, rebelled against heavy taxation and property foreclosures. The federal government under the Articles proved incapable of responding effectively to this domestic crisis, alarming many political leaders who feared broader civil unrest.

The Constitutional Convention

In February 1787, Congress authorized a convention in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation. When delegates assembled in May, however, their ambitions quickly expanded beyond mere revision. Led by figures like James Madison of Virginia, the convention soon shifted toward creating an entirely new constitutional framework.

This move from reform to revolution reflected growing recognition that the Articles' fundamental structure was inadequate for national governance. Although delegates generally agreed that change was necessary, they disagreed sharply about what form that change should take. Any new governmental structure would inevitably create winners and losers among states and interest groups, leading to intense debates throughout the summer of 1787.

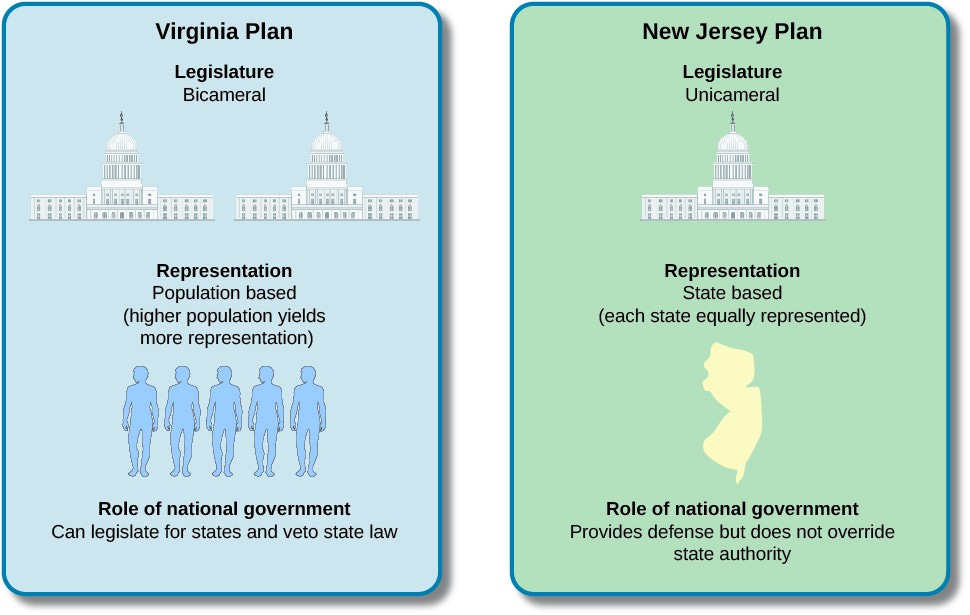

The Virginia Plan

James Madison's Virginia Plan proposed a strong national government with proportional representation in both houses of Congress. The plan called for:

A bicameral legislature with representation based on state population.

A lower house elected by the people.

An upper house chosen by state legislatures.

An executive and judicial branch chosen by Congress.

National government power to enforce laws and veto state legislation.

Major opposition came from two sources. First, small states were understandably concerned that they would have significantly less representation in the popularly-elected House than they had enjoyed under the Articles of Confederation. Second, another group opposed the degree of power states would surrender to the newly empowered national government.

The New Jersey Plan

Smaller states rallied behind William Paterson's New Jersey Plan, which proposed:

A unicameral legislature with equal representation for all states.

Expanded federal powers compared to the Articles of Confederation.

Majority rather than supermajority voting requirements.

These two plans divided the delegates into dug in camps that resulted in stalemate.

The Great Compromise

The convention ultimately bridged these competing visions through the Great Compromise, which created:

A House of Representatives based on population (like the Virginia plan).

A Senate with equal state representation (like the New Jersey plan).

Revenue legislation originating in the House.

Simple majority voting requirements for most legislation.

An empowered national government with a chief executive.

As James Madison later reflected in Federalist No. 39:

[W]e find it neither wholly NATIONAL nor wholly FEDERAL. Were it wholly national, the supreme and ultimate authority would reside in the MAJORITY of the people of the Union; and this authority would be competent at all times, like that of a majority of every national society, to alter or abolish its established government. Were it wholly federal, on the other hand, the concurrence of each State in the Union would be essential to every alteration that would be binding on all. The mode provided by the plan of the convention is not founded on either of these principles. In requiring more than a majority, and principles. In requiring more than a majority, and particularly in computing the proportion by STATES, not by CITIZENS, it departs from the NATIONAL and advances towards the FEDERAL character; in rendering the concurrence of less than the whole number of States sufficient, it loses again the FEDERAL and partakes of the NATIONAL character.

This hybrid character of the new government reflected not abstract design principles but the practical necessity of compromise among competing interests.

The Constitution established three branches of government with carefully distributed powers. Unlike the Articles of Confederation, which created only a legislative body, the Constitution created a complete governmental structure with executive and judicial branches to complement the legislative.

The Legislative Branch (Article I)

Congress, detailed in Article I, was designed as the primary federal power, reflecting the Framers' belief that the legislative branch should be the central force in American government. This primacy is evident in both the Constitution's structure—Article I is by far the longest and most detailed article—and in the comprehensive powers granted to Congress.

The bicameral legislature embodied a careful balance between popular and state interests, creating a complex system of representation and authority. The House of Representatives, with its population-based representation and frequent elections every two years, was designed to be closely responsive to the public will. Representatives would be allocated among states based on population counts (conducted through the decennial census), ensuring that more populous states would have greater influence in this chamber.

The Senate, by contrast, embodied the principle of state equality, with each state receiving two senators regardless of population. Originally appointed by state legislatures rather than directly elected, senators served longer six-year terms, with only one-third of the chamber facing election in any given cycle. This structure was intended to make the Senate a more deliberative body, less subject to popular passions and more focused on long-term national interests.

Congress received specific expressed powers that addressed the major weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. These included:

The power to collect taxes, addressing the previous inability to fund national priorities.

Authority to borrow money on the nation's credit.

Regulation of commerce between states and with foreign nations.

The power to declare war and maintain armed forces.

The Constitution included the Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the "elastic clause," which has proven crucial to congressional power. This provision allows Congress to make laws needed to execute its expressed powers, providing flexibility to address unforeseen circumstances while maintaining constitutional boundaries.

The Executive Branch (Article II)

The creation of the executive branch reflected the Framers' deep ambivalence about executive power. Having just fought a revolution against King George III, they were deeply wary of creating an office that might evolve into another monarchy. Yet their experience under the Articles of Confederation had also taught them the practical necessity of having an executive to implement laws and make decisive decisions, particularly in emergencies and wartime.

Their solution was to create a constitutionally limited presidency that was intentionally constrained in its powers. Though the modern presidency appears quite powerful, the actual constitutional text grants surprisingly few powers to the president, especially when compared to Congress's extensive Article I authorities.

The Constitution provides the president with a limited set of specific powers, many of which require Congress assent or consent to exercise:

Appointing federal judges and officials (subject to Senate confirmation).

Conducting diplomacy with foreign nations.

Serving as commander in chief of the military (after Congress declares war).

Delivering information about the state of the union.

Vetoing legislation (after both chambers or Congress have voted in favor of a bill).

Granting pardons for federal crimes.

Notably, almost all of these presidential powers come with significant congressional checks. The appointment power requires Senate confirmation for major positions. While the president serves as commander in chief, only Congress can declare war and control military funding. Even in foreign affairs, where the president leads diplomacy, the Senate must ratify treaties.

The veto power, perhaps the president's strongest constitutional tool, is itself primarily negative in nature. The president can reject legislation but cannot compel Congress to act or pass new laws. Even this negative power is limited—Congress can override a veto with a two-thirds majority in both chambers. The president has no formal role in proposing legislation, despite the modern expectation that presidents will propose policy agendas and draft budgets.

Article II's vagueness about executive power has led to significant debate and evolution over time. The phrase "executive power" is never clearly defined, and the requirement that the president "take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed" has been interpreted in various ways. This constitutional ambiguity has allowed for significant expansion of presidential power through:

Development of executive orders and other presidential directives.

Growth of the administrative state (bureaucracy).

However, the Constitution's original design envisioned a much more limited role—primarily focused on executing laws rather than making policy, and heavily dependent on congressional cooperation rather than unilateral action. The modern presidency's broad powers and central policymaking role represent a significant departure from the Framers' initial conception of a constrained executive branch.

The Electoral College

The method of presidential selection was also debated at the Constitutional Convention. The Electoral College emerged as a compromise solution that balanced multiple principles:

Federalism: Each state receives electoral votes equal to its total congressional representation (House plus Senate seats), giving smaller states slightly disproportionate influence.

State authority: State legislatures were empowered to determine how electors would be chosen, maintaining state influence in the process.

Independent judgment: Electors would meet in their respective states to cast votes, preventing collusion and allowing for deliberation.

Congressional backstop: If no candidate received an electoral majority, the House of Representatives would choose the president, with each state delegation casting one vote.

This complex system reflects the hybrid nature of the Constitution itself—neither fully national nor fully federal, just like the Great Compromise overall. The Electoral College gives states a defined role in selecting the president while creating a mechanism that operates independently of both Congress and direct popular vote.

Today, most states award all their electoral votes to the statewide popular vote winner, creating a "winner-take-all" system that can produce presidents who lose the national popular vote but win in the Electoral College—a result that has occurred in 2000 and 2016.

This tension between the Electoral College's original design and its contemporary operation illustrates how constitutional mechanisms can evolve through practice while maintaining their formal structure. It also highlights ongoing debates about representation and federalism in the American system.

The Judicial Branch (Article III)

Although Article III is the shortest of the Constitution's three articles establishing the federal branches, its brevity belies the judiciary's eventual importance in the American system. The Framers' relative inattention to judicial details allowed for significant evolution in the courts' role and structure over time.

The Constitution establishes the Supreme Court as the nation's highest judicial body while leaving its size and internal organization to Congress. It also permits—but does not require—the creation of lower federal courts, a flexibility that Congress exercised in the Judiciary Act of 1789 by establishing a system of district and circuit courts.

The selection process for federal judges combines influences from multiple sources:

Presidential nomination of all federal judges.

Senate confirmation requirement.

Life tenure during "good behavior."

This structure aims to create an independent judiciary, insulated from political pressures but still ultimately derived from democratic processes.

The judiciary's most significant power—judicial review, or the authority to declare laws unconstitutional—was not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution. This power would be established through precedent in Marbury v. Madison (1803), when Chief Justice John Marshall declared that "it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.”

Amending the Constitution

The Framers faced a crucial dilemma in deciding how to modify the Constitution over time. Their experience with the Articles of Confederation—which required unanimous state approval for changes—had shown how overly strict amendment rules could lead to paralysis. Yet they also worried about making the Constitution too easy to change, fearing that a simple majority could hastily undo their carefully crafted compromises.

The solution they devised reflects the Constitution's broader pattern of balancing competing interests and creating multiple pathways to action.

Proposal: Amendments can be proposed either by a two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress or by a constitutional convention called by two-thirds of state legislatures.

Ratification: Proposed amendments must be ratified by three-fourths of states, either through state legislatures or state conventions.

This process balances flexibility with stability. It allows the Constitution to adapt to changing circumstances while ensuring that amendments reflect broad national consensus rather than temporary majorities.

In practice, all but one of the Constitution's 27 amendments have followed the congressional route. The convention method, while theoretically available, has never been successfully used.

The difficulty of the amendment process is evident in the statistics: of the thousands of amendments proposed in Congress, only 33 have received the necessary two-thirds approval, and just 27 have been ratified by the states. The most recent amendment—the 27th, concerning congressional pay raises—was ratified in 1992.

This high barrier to constitutional change has had several important consequences:

The Constitution's core structure has remained remarkably stable.

Much constitutional evolution occurs through judicial interpretation rather than formal amendment.

Significant political movements often focus on statutory change rather than constitutional amendment.

Some widely supported reforms remain unimplemented due to difficulties amending the Constitution.

The amendment process thus exemplifies a central tension in American constitutionalism: the balance between stability and adaptability. While the difficulty of amendment has preserved the Constitution's basic framework, it has also forced American democracy to find other ways to evolve—through legislation, judicial interpretation, and changing political practices.

Ratification and the Bill of Rights

Once the delegates completed their work in September 1787, they faced the challenge of ratification. The Articles of Confederation required unanimous state consent for amendments, but the Convention specified that the new Constitution would take effect when ratified by nine of the thirteen states, deliberately circumventing the Articles' requirements.

Additionally, the Convention called for special state ratifying conventions rather than submitting the Constitution to state legislatures, which might resist surrendering their powers. This strategy proved effective but controversial, illustrating the revolutionary nature of the Constitution's adoption.

Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists

The ratification debate divided Americans into two broad camps:

Federalists supported the Constitution, arguing that a stronger national government was necessary for effective governance and security.

Anti-Federalists opposed the Constitution, fearing concentrated power and the lack of explicit protections for individual rights.

The Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, made their case in a series of essays now known as The Federalist Papers. They argued that the Constitution's checks and balances would prevent tyranny while enabling effective governance.

Anti-Federalists, including Patrick Henry, George Mason, and Richard Henry Lee, countered that the Constitution created too powerful a central government that would eventually override state authority and individual liberties. They particularly criticized the absence of a bill of rights protecting individual freedoms against governmental encroachment.

To secure ratification in key states, Federalists promised to add a bill of rights once the Constitution was adopted. James Madison, who initially opposed a bill of rights as unnecessary, later led the effort to draft these amendments in the First Congress. Ten of these amendments were ratified in 1791, becoming what we now call the Bill of Rights. Ratifying the Constitution was just as contentious as many of the political debates raging today.

The Constitution's Enduring Influence

The United States Constitution is remarkably brief—approximately 4,400 words plus amendments. This conciseness reflects not only 18th-century drafting conventions but also deliberate ambiguity on many contentious issues. Where delegates could not reach consensus, they often used vague language that postponed resolution of conflicts.

This constitutional ambiguity has enabled adaptation over time through various mechanisms:

Judicial interpretation has clarified ambiguous provisions and applied constitutional principles to new circumstances.

Congressional legislation has implemented constitutional powers in ways the Framers could not have anticipated.

The president has taken on a much larger role in the political system than the Framers had imagined or would be comfortable with.

Informal practices and norms have developed to fill gaps in the constitutional framework.

This flexibility has allowed the Constitution to endure through dramatic social, economic, and technological changes. Yet this same ambiguity creates ongoing tensions. Contemporary debates about executive power, federalism, and individual rights continue to reference constitutional text and original understanding, even as circumstances have changed dramatically. The Constitution's balance between stability and adaptability remains both its greatest strength and its most persistent challenge.

Political scientists and constitutional scholars continue to debate whether our constitutional system adequately addresses contemporary challenges like polarization and gridlock. The multiple veto points and supermajority requirements that prevent tyranny can also impede effective governance in a polarized environment. These tensions reflect the fundamental trade-off the Framers confronted: how to create a government powerful enough to govern effectively yet constrained enough to preserve liberty.

Understanding the Constitution as the product of specific historical circumstances and political compromises—rather than as a perfect blueprint for governance—helps us appreciate both its enduring principles and its inevitable limitations. The path dependence that shapes our current institutions reminds us that constitutional design reflects not just abstract principles but practical necessities and political realities.

Key Terms

Path dependence: The concept that historical decisions and institutional designs continue to shape current political structures and behaviors.

Articles of Confederation: America's first constitution (1781-1789), which created a weak national government with limited powers.

Great Compromise: The agreement creating a bicameral legislature with proportional representation in the House and equal representation in the Senate.

Elastic clause: The constitutional provision (Article I, Section 8) authorizing Congress to make laws "necessary and proper" for executing its enumerated powers.