Who Decides Who Decides?

The paradox of participation in a system where your vote probably won't change the outcome.

Learning Objectives

Understand the institutional design of American elections and how elections serve as accountability mechanisms.

Analyze the principal-agent relationship between voters and elected officials.

Identify patterns in voter participation and their implications for representation.

Evaluate different theories of voter decision-making and candidate positioning.

Explain how electoral systems shape political behavior and outcomes.

Introduction: Elections as Democratic Linkage

Elections are the fundamental mechanism through which citizens in a representative democracy exercise power over their government. Competitive elections are what ultimately give citizens a meaningful choice in who governs them. Without regular, fair elections, there would be no means for citizens to hold government officials accountable or to influence the direction of public policy.

Yet the American electoral system is far more complex than simply casting ballots and counting votes. It reflects historical compromises, evolving understandings of citizenship and representation, and the tension between democratic and republican principles that has characterized American politics since the founding era. As constitutional framers like James Madison were deeply concerned about "the tyranny of the majority," they designed a system that would both represent the people and constrain popular passions—a republic rather than a direct democracy.

Today, this system continues to evolve as Americans debate fundamental questions: Who should be able to vote? How should votes be translated into representation? What responsibility do elected officials have to their constituents? These questions go to the heart of democratic governance and reveal ongoing tensions in how Americans understand representation and accountability.

By examining how elections function—in theory and in practice—we can better understand both the promise and the limitations of American democracy. This chapter explores the institutional design of American elections, patterns of voter participation, models of voter decision-making, and the strategic calculations of candidates, all with an eye toward understanding how elections serve as the critical linkage between citizens and their government.

Representative Democracy as a Principal-Agent Relationship

From Direct Democracy to Representative Democracy

The framers of the Constitution deliberately established what we now call a representative democracy rather than a direct democracy.

In a direct democracy, citizens make policy decisions themselves through voting, referendums, or town meetings. While this approach maximizes citizen participation, it becomes increasingly unwieldy as populations grow and policy questions become more complex. How could 330 million Americans meaningfully deliberate and vote on every policy question facing the nation?

Representative democracy offers a solution to this coordination problem by allowing citizens to select agents who will make decisions on their behalf. Rather than voting directly on policy questions, citizens vote for representatives who are empowered to study issues in depth and make decisions. This approach—often referred to as a republic—creates a layer of insulation between popular will and government action.

This distinction between direct democracy and representative democracy is fundamental to understanding American elections. When you vote for a member of Congress, you are not voting directly on policy; you are selecting someone to (hopefully) represent your interests in the policy-making process.

The Principal-Agent Problem in Democratic Representation

This system of delegation creates a principal-agent relationship. In this relationship, voters (the principals) delegate authority to elected officials (the agents) who are supposed to act on the voters' behalf. This arrangement creates efficiencies—voters don't need to become experts on every policy issue—but it also introduces potential problems.

The principal-agent problem occurs when agents pursue their own interests rather than faithfully representing their principals. In the context of elections, this might happen when elected officials:

Vote contrary to constituent preferences.

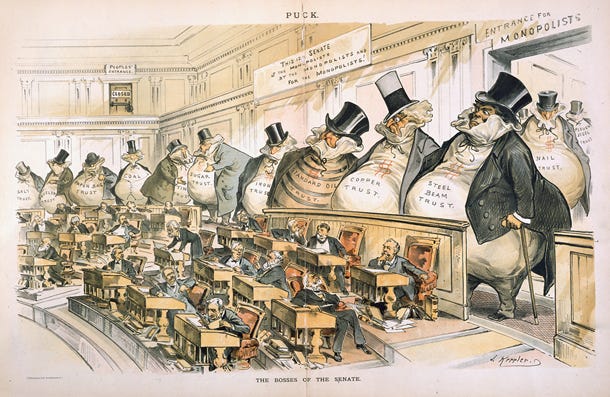

Favor special interests who provide campaign contributions.

Shirk their duties by missing votes or committee meetings.

Engage in corruption or self-dealing.

These behaviors are possible because of information asymmetry—elected officials typically know more about legislation, procedures, and policy details than their constituents. This asymmetry makes it difficult for voters to monitor their representatives effectively.

Elections serve as the primary mechanism for addressing this principal-agent problem. Regular elections force representatives to consider voter preferences when making decisions, as they must eventually face voters' judgment. The threat of being voted out of office—what political scientists call "electoral accountability"—helps align representatives' incentives with their constituents' interests while they serve in government.

What Elections Do: Three Key Functions

Elections serve at least three critical functions in a representative democracy:

Selection of agents: Elections give citizens a direct say in who will represent them. Citizens can use whatever criteria they consider important—policy positions, character, experience, or descriptive representation—to choose their representatives.

Inducing responsiveness: The fact that elected officials must regularly stand for reelection motivates them to be responsive to constituent concerns. Because politicians typically want to keep their jobs, they have an incentive to avoid actions that might alienate voters.

Enabling "fire alarm" oversight: While most citizens don't closely monitor their representatives' activities, interested groups like journalists, advocacy organizations, and opposition parties do. When these watchdogs detect problematic behavior, they can "pull the fire alarm," alerting voters who can then respond at the ballot box. This system allows ordinary citizens to benefit from oversight without having to pay close attention themselves.

Together, these functions help mitigate the principal-agent problem inherent in representative democracy. They provide mechanisms for citizens to select good representatives initially, incentivize those representatives to act in citizens' interests while in office, and remove representatives who fail to do so. As we will see, these mechanisms have limitations that affect how well elections actually function as accountability tools.

The Evolving American Electorate

The Expansion of Voting Rights

The question of who should be allowed to participate in elections has been contentious throughout American history. The Constitution did not explicitly define who could vote, leaving this decision largely to the states. Initially, the franchise was limited primarily to white, property-owning men. Over time, through constitutional amendments, legislation, and court decisions, voting rights have expanded to include a much broader segment of the population.

When the United States was founded, many states limited voting to those who owned substantial property, effectively restricting political participation to wealthier, white citizens. One of the earliest significant expansions of voting rights came in the early 19th century with the elimination of property requirements for white men.

Between 1800 and 1830, many states revised their constitutions to eliminate or significantly reduce property requirements for voting. This democratization coincided with (though was not caused by) the rise of Andrew Jackson in American politics. Jackson and his Democratic Party strongly championed the principle of universal white male suffrage, helping consolidate this democratic expansion. By 1840, most adult white men had secured the right to vote.

Later key expansions of voting rights included:

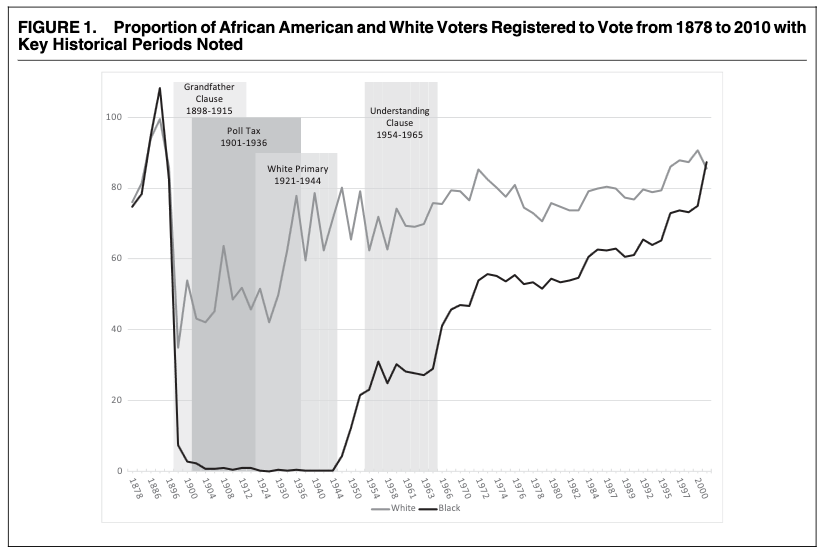

15th Amendment (1870): Formally prohibited denial of voting rights based on "race, color, or previous condition of servitude," but its promise remained largely unfulfilled for decades as Southern states implemented poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and violent intimidation to prevent Black men from exercising this right.

19th Amendment (1920): Prohibited denial of voting rights based on sex.

24th Amendment (1964): Prohibited poll taxes in federal elections.

Voting Rights Act (1965): Prohibited discriminatory voting practices that had been used to disenfranchise Black voters.

26th Amendment (1971): Lowered the voting age to 18.

Despite these formal expansions, practical barriers to voting persisted for many Americans, especially racial minorities. Literacy tests, complex registration procedures, and intimidation continued to limit political participation well into the 20th century. Even today, debates continue about voter identification laws, felon disenfranchisement, and other policies that affect who can participate in elections.

The expansion of voting rights reflects an evolution in American understandings of democratic citizenship—from a privilege of the propertied few to a right of all adult citizens. This evolution has made the American electorate increasingly diverse, though participation rates still vary significantly across demographic groups.

Participation Gaps: Who Votes and Who Doesn't

Despite the expansion of formal voting rights, actual participation in elections varies considerably. In recent presidential elections, turnout has hovered around a notable high of 60-65% of eligible voters. However, past presidential elections have seen turnout rates closer to 50%, with even lower rates in midterm and local elections. This means that a significant portion of the electorate is effectively self-disenfranchising by not participating.

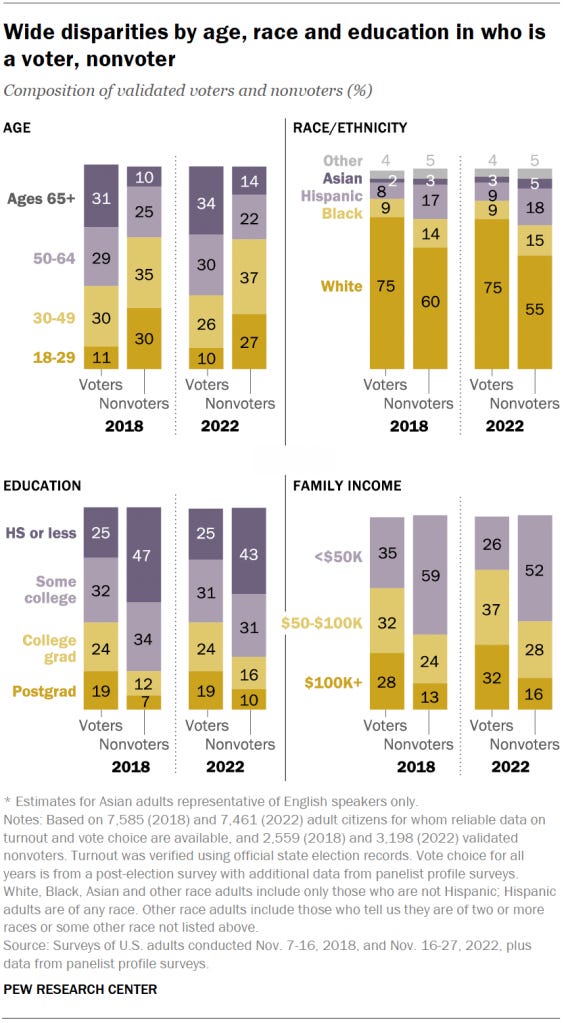

Participation is not randomly distributed across the population. Some groups consistently turn out at higher rates: older voters, more educated voters, higher-income voters, and white voters.

These disparities raise important questions about representation. If some groups vote at much higher rates than others, elected officials may be more responsive to the interests of high-participation groups. This creates a potential feedback loop: when elected officials are more responsive to groups that vote frequently, members of low-participation groups may become even more disenchanted with politics, further reducing their incentive to vote.

The Paradox of Voting

Yet, from a rational choice perspective, the fact that anyone votes at all presents something of a puzzle. In a large electorate, the probability that any individual vote will decide an election is vanishingly small—effectively zero in most cases. Meanwhile, voting imposes real costs: time spent researching candidates, traveling to polling places, waiting in line, and actually casting a ballot.

This creates what political scientists call the paradox of voting. If voting imposes costs but the probability of affecting the outcome is essentially zero, why do rational people vote at all?

Political scientists have proposed several explanations:

Expressive benefits: Voting provides psychological benefits—a sense of civic duty fulfilled, an expression of political identity, or the satisfaction of supporting a preferred candidate.

Social pressure: Voting is a social norm, and people may feel pressure from friends, family, or community to participate.

Incomplete information: Voters may overestimate the impact of their individual vote.

Group loyalty: Voters may see themselves as part of a group with shared interests and vote to support those collective interests.

The paradox of voting helps explain participation gaps. For individuals with more resources (time, money, education), the costs of voting are relatively low compared to the expressive benefits. For those with fewer resources or weaker political attachments, the calculation may tilt against participation. This creates a troubling dynamic where those who might benefit most from political change are often least likely to vote.

How Voters Decide: Models of Electoral Choice

When voters do decide to participate in elections, how do they choose which candidates to support? Political scientists have developed several models to explain voter decision-making.

Party Identification

The single strongest predictor of vote choice is party identification—a voter's psychological attachment to a political party. Most Americans identify with either the Democratic or Republican party, and this identification strongly influences their voting behavior. In the 2024 presidential election, approximately 95% of Democrats voted for the Democratic candidate and 94% of Republicans voted for the Republican candidate.

Party identification functions as what political scientists call a "perceptual screen," influencing how voters interpret political information. When faced with complex policy debates, voters often rely on party cues to determine their position. If they identify as a Democrat, they may be predisposed to support positions advocated by Democratic leaders, and vice versa for Republicans.

This party loyalty is not merely blind tribalism. Parties generally represent coherent ideological positions and policy platforms that align with voters' preferences on key issues or provide coherent positions on issues voters haven’t deeply considered. When voters identify with a party, they are often expressing affinity with that party's overarching approach to governance, even if they disagree on some issues.

Policy and Issue Voting

While party identification is a strong predictor of vote choice, many voters also consider specific policies and issues when making their decisions. Two models of issue voting are particularly influential:

Prospective voting occurs when voters choose candidates based on their promises about future actions. Voters assess candidates' campaign platforms and statements to determine which candidate is most likely to pursue policies they favor. For example, a voter concerned about climate change might support a candidate who promises aggressive action to reduce carbon emissions.

Retrospective voting occurs when voters evaluate incumbents based on their past performance. Rather than focusing on promises about the future, voters ask, "Am I better off now than I was when this official took office?" This approach treats elections as opportunities to reward good performance or punish bad performance. Economic conditions are particularly important for retrospective voting, with incumbents typically benefiting from strong economies and suffering during economic downturns.

To an extent, voters use both of these perspectives when making an electoral decision. And the issues that matter most to voters change over time. In some elections, economic concerns dominate; in others, foreign policy or social issues may be more salient. The 2024 presidential election, for instance, saw abortion, inflation, and immigration emerge as particularly important issues for many voters.

Candidate Characteristics

Beyond party and issues, voters also consider candidates' personal characteristics. These might include:

Experience and qualifications: Previous public service, professional background, educational credentials.

Character traits: Honesty, integrity, compassion, leadership ability.

Demographic characteristics: Gender, race, age, religion, regional identity.

Personal style: Communication skills, relatability, charisma.

These characteristics can serve as useful heuristics or shortcuts. For example, a voter might reasonably infer that a candidate who served in the military values national security, or that a candidate who worked as a teacher cares about education policy. Similarly, shared demographic characteristics might signal to voters that a candidate will understand and represent their interests and provide descriptive representation.

How Electoral Systems Shape Political Behavior

Just as electoral systems structure voters' choices, they also shape how candidates position themselves to appeal to voters.

The Median Voter Theorem

A foundational concept in understanding candidate strategy is the median voter theorem, developed by economist Anthony Downs. This theorem suggests that in a two-candidate election with a single dimension of competition (like a liberal-conservative spectrum), both candidates will position themselves near the median voter to maximize their vote share.

The logic is straightforward. Imagine voters arranged on a spectrum from most liberal (1) to most conservative (10), with an equal number of voters at each position. If Candidate A positions themselves at 3 and Candidate B at 7, all voters to the left of 5 will prefer Candidate A, while all voters to the right of 5 will prefer Candidate B. If Candidate A moves to position 4, they will still capture all voters to the left but will also pick up some moderate voters, expanding their vote share. This creates pressure for both candidates to converge toward the center.

In practice, the median voter theorem helps explain why candidates often moderate their positions after winning party primaries. During primaries, candidates appeal to their party's base (which is typically more ideologically extreme than the general electorate). Once nominated, candidates typically shift toward the center to appeal to moderate voters who will decide the general election.

However, several factors complicate this simple model:

Multiple issue dimensions: Voters care about many issues, not just a single liberal-conservative spectrum.

Primary elections: The need to win party nominations pushes candidates away from the median voter and it can be difficult to pivot to the center after taking extreme positions in the primary.

Partisan polarization: As the parties become more ideologically distinct, candidates face stronger pressure to adhere to party orthodoxy.

Turnout effects: Candidates sometimes prioritize mobilizing their base over appealing to the median voter to increase their vote share.

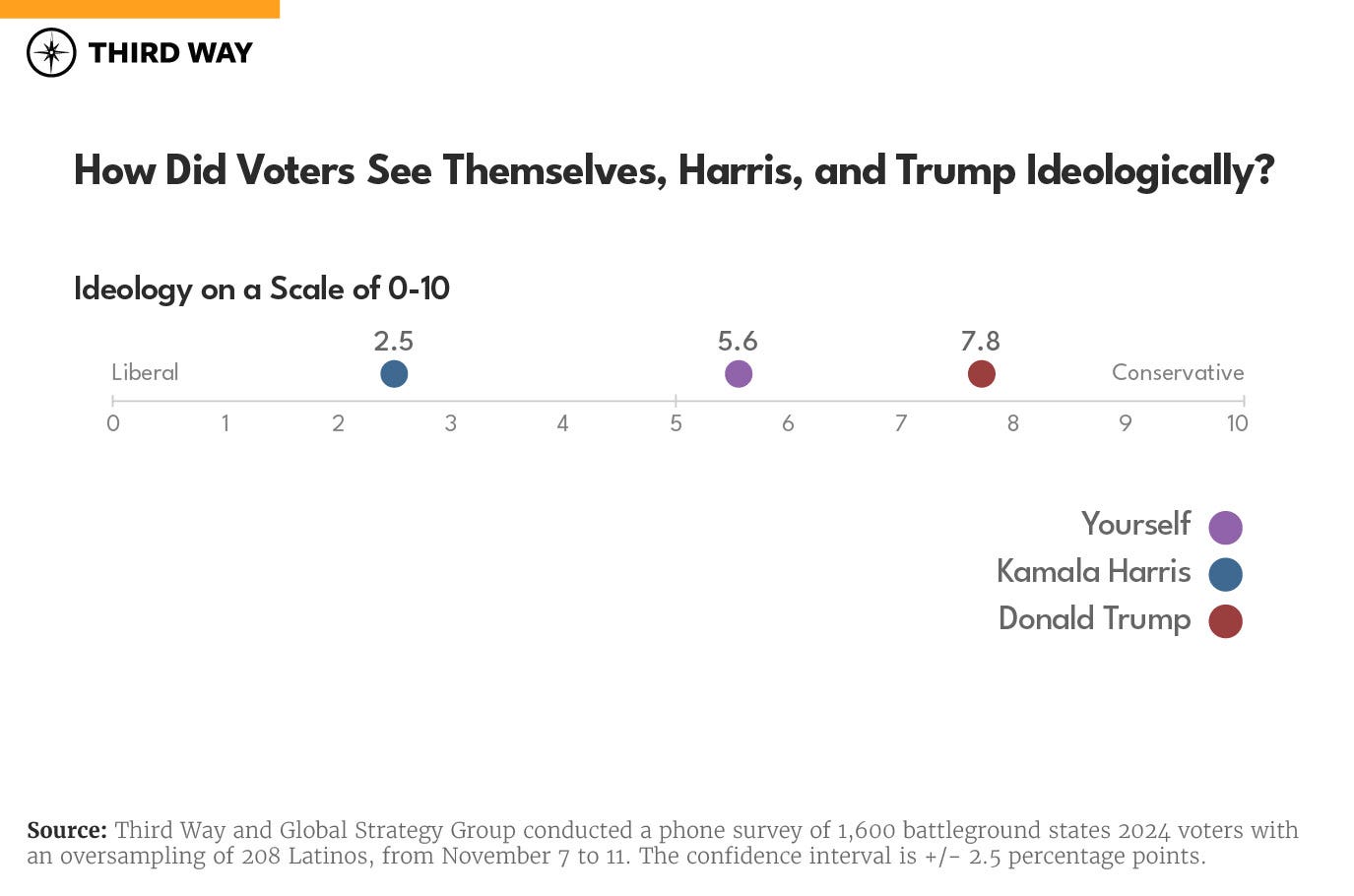

Despite these complications, the median voter theorem provides useful insights into candidate behavior. It helps explain why candidates carefully calibrate their positions based on electoral contexts. It is also consistent with results of recent presidential elections. In 2024, some post-election surveys have shown that voters thought Trump was ideologically closer to them on average than Harris.

Elections as Coordination Mechanisms

Beyond selecting representatives, elections serve important coordination functions within the political system. They help:

Aggregate voter preferences into clear choices between competing visions.

Establish mandates for policy action by indicating public support for certain candidates or approaches.

Facilitate peaceful transitions of power by providing clear rules for determining winners.

Create legitimacy for governance by securing public consent.

These functions depend on broad acceptance of election results as legitimate. When significant portions of the electorate question the fairness or accuracy of elections, these coordination benefits diminish, potentially threatening democratic stability.

Conclusion: Elections and Democratic Accountability

Elections stand at the heart of democratic governance, providing the essential mechanism through which citizens influence their government. They serve both practical and symbolic functions—selecting leaders, aligning representatives' incentives with constituent interests, and legitimizing government authority.

Yet as we have seen, elections are complex institutions shaped by history, strategic behavior, and social context. Their effectiveness as accountability mechanisms depends on multiple factors: who participates, how voters make decisions, how candidates position themselves, and how electoral rules translate votes into representation.

The American electoral system reflects an ongoing tension between democratic and republican principles—between direct popular control and filtered representation. This tension, present since the founding, continues to shape debates about electoral reform, from proposals to abolish the Electoral College to concerns about gerrymandering and campaign finance.

Elections are not perfect mechanisms of accountability, but they provide essential opportunities for citizens to exercise their sovereignty and shape the direction of government.

Key Terms

Representative democracy: A system of government where citizens elect representatives to make decisions on their behalf rather than voting directly on policies.

Electoral accountability: The mechanism by which elected officials are held responsible for their actions through regular elections.

Fire alarm oversight: A system where interested third parties monitor government behavior and alert the public to problems, allowing citizens to benefit from oversight without monitoring directly.

Paradox of voting: The puzzle of why rational individuals vote when the probability of affecting the outcome is effectively zero while voting imposes real costs.

Prospective voting: Voting based on candidates' promises about future actions.

Retrospective voting: Voting based on evaluation of incumbents' past performance.

Median voter theorem: The theory that in a two-candidate election with a single dimension of competition, both candidates will position themselves near the median voter to maximize their vote share.