Political Scientists Love Parties. But You Probably Hate Them.

Understanding the paradox of parties in American democracy.

Learning Objectives

Understand the paradox of American attitudes toward political parties.

Analyze three key roles parties play in American politics.

Identify the structural factors that reinforce the two-party system.

Evaluate how parties have evolved to reflect and shape social divides.

The Paradox of American Parties

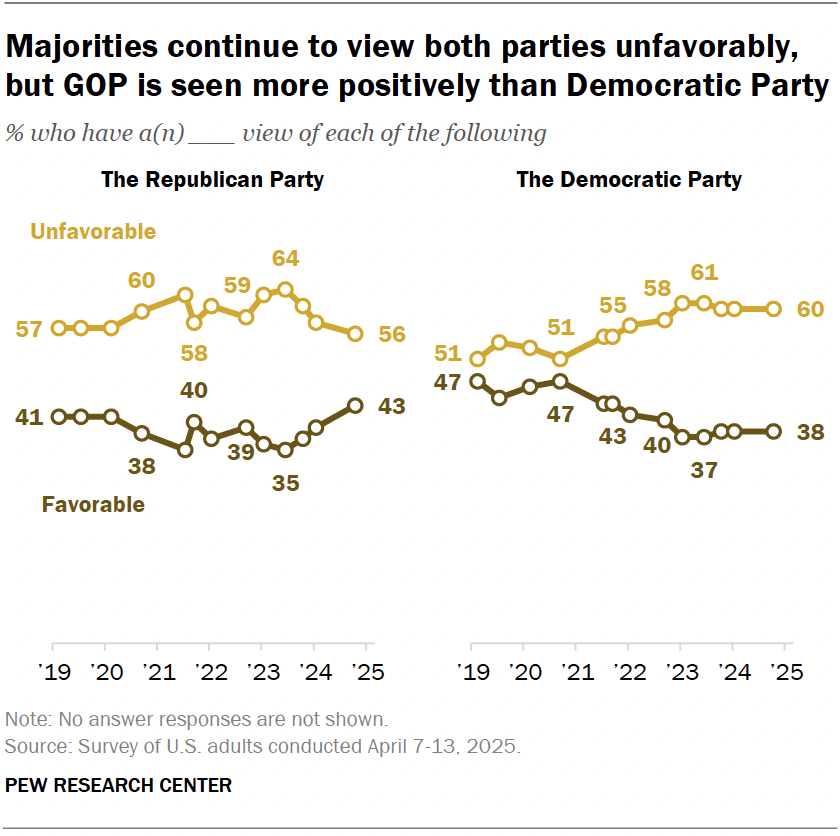

Americans have a complicated relationship with political parties. Polls consistently show deep dissatisfaction with both major parties, with over a quarter of Americans holding unfavorable views of both the Democrats and Republicans. Most citizens believe parties spend too much time on partisan disagreements rather than substantive issues. Yet despite this dissatisfaction, the vast majority of Americans identify with one of the two major parties, and third-party candidates rarely receive significant support in national elections.

This paradox—widespread criticism of parties alongside their continued dominance—reflects a tension present since the nation's founding. The framers of the Constitution neither provided for, nor anticipated, political parties. In fact, many explicitly warned against them. John Adams wrote, "A division of the republic into two great parties...is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil under our Constitution." George Washington similarly cautioned against "the baneful effects of the spirit of party" in his Farewell Address.

Despite these warnings, parties emerged almost immediately. By the early 1790s, Federalists and Democratic-Republicans had organized to compete for control of the new government. This rapid development suggests that parties fulfill essential functions in democratic governance.

Understanding this dynamic helps explain a central paradox of American politics: political parties are simultaneously one of our most criticized institutions and one of our most enduring. As political scientist E.E. Schattschneider (1942) famously observed, "Modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of parties." By examining what parties do, how they are structured, and how they have evolved, we can better understand both their persistence and the persistent dissatisfaction they generate.

What Are Political Parties?

Political parties are not just the Democrats and Republicans we see in the White House or Congress. They are coalitions of politicians, interest groups, activists, and voters who seek to control government by winning elections. Unlike single-issue advocacy groups, parties address a broad range of policy areas and attempt to build majority coalitions capable of governing.

Political parties serve essential functions in democratic systems:

They solve collective action problems by coordinating group activities.

They promote issue platforms related to broader political and ideological goals.

They translate public preferences into policy through electoral competition and control of government.

These functions are particularly important in the American constitutional system, with its separated powers and multiple veto points. Without parties to coordinate action across institutions and build stable coalitions, the fragmented American system might struggle to produce coherent policy outcomes.

The formal party organizations—the Democratic National Committee and Republican National Committee—represent only a small part of these broader party coalitions that include elected officials, activist networks, aligned interest groups, partisan media outlets, and millions of voters who identify with the party label. This complex network structure helps explain both the resilience and the internal tensions that characterize American parties.

The Three Roles of Political Parties

Political scientists often analyze parties as having three distinct roles in the political system: parties in government, parties as organizations, and parties in the electorate. Understanding these distinct components helps explain how parties function across different domains.

Parties in Government

When candidates win election to public office, they join their fellow partisans to form the party in government. These elected officials work together to advance shared policy goals, coordinate legislative strategy, and exercise governmental power.

Parties in government perform several crucial functions:

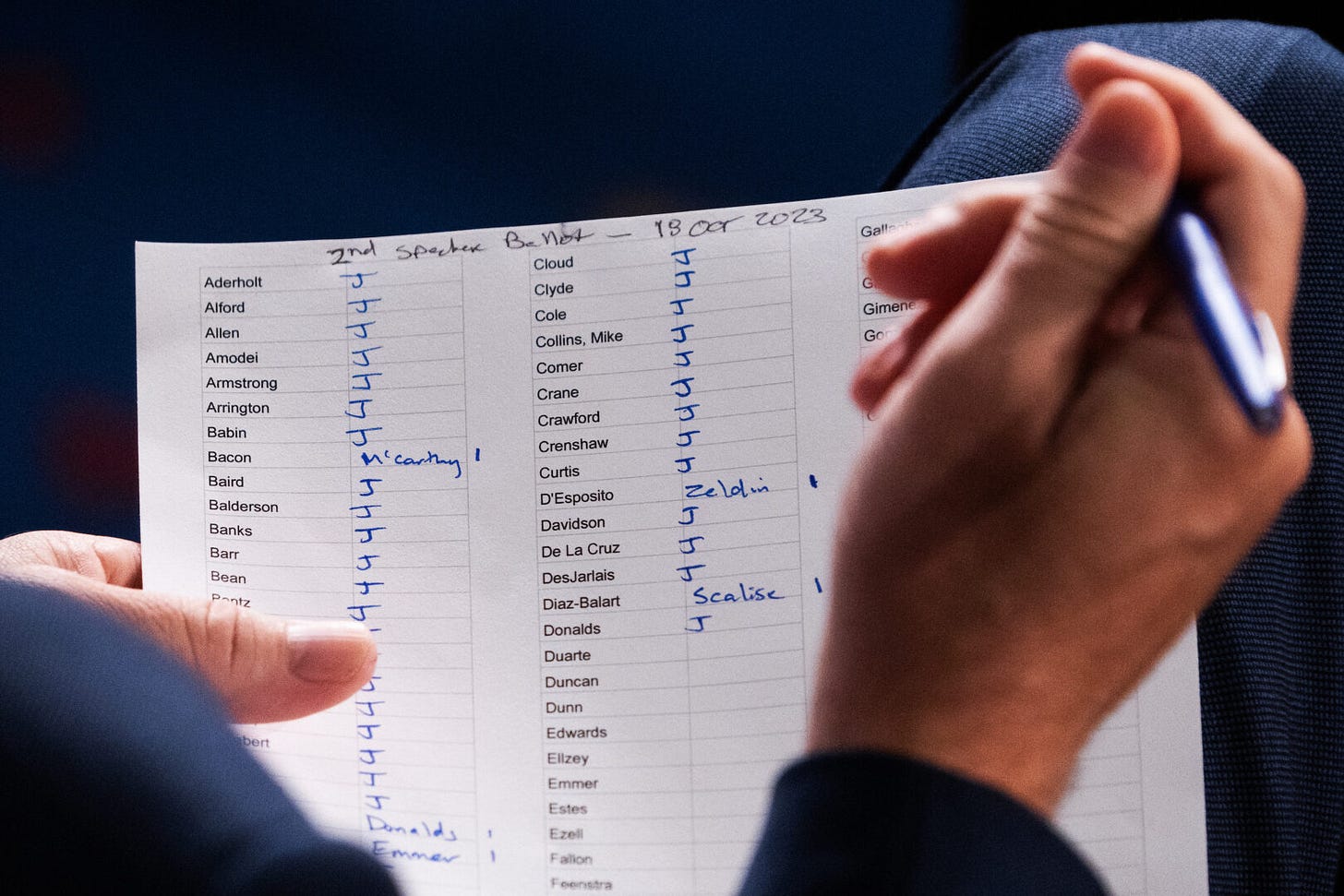

Leadership selection: Parties select leaders like the Speaker of the House, Senate Majority Leader, and committee chairs for the majority party, as well as Minority Leaders and ranking committee members for the minority party. These leadership positions help coordinate action within each party, reducing the transaction costs of building coalitions and enabling both parties to act more cohesively. While majority leadership controls the legislative agenda and procedural rules, minority leadership coordinates opposition strategy and alternative policy proposals, ensuring both parties can function effectively as collective entities rather than as collections of individual legislators with divergent preferences.

Reducing transaction costs: Rather than negotiating new coalitions for each policy issue, parties provide stable coalitions that can negotiate from common starting points. It would be particularly difficult and inefficient if, each time someone wanted to pass a bill, they had to gather votes from scratch. This efficiency is particularly valuable in the U.S. system, where laws must pass through multiple veto points.

Introducing and passing legislation: Parties serve as vehicles for developing and advancing policy priorities through the legislative process. Members of the same party typically support legislation proposed by their partisan colleagues and oppose bills introduced by the opposing party. This partisan voting pattern provides predictability in the legislative process and helps lawmakers overcome the collective action problem of building support for bills. Parties also develop legislative packages that reflect shared ideological principles, allowing individual members to point to party accomplishments when seeking reelection.

Policy coordination: Parties help coordinate policy across different branches and levels of government. When a party controls multiple institutions—the presidency, House, and Senate, for instance—it can pursue a more coherent policy agenda than would be possible with independent actors in each position.

The Constitution's separation of powers makes governing difficult. Parties emerged partly as a solution to these barriers, creating informal connections across formal institutional boundaries. When the same party controls multiple branches, policy coordination becomes easier despite the constitutional separation.

Yet, even within a single institution like Congress, parties help individuals overcome collective action problems through shared benefits. Without parties, legislators might focus solely on issues directly relevant to their districts and avoid cooperating on issues that conflict with their own narrow self-interest, leading to fragmented efforts and few legislative accomplishments. Parties solve this dilemma by creating a structure for sustained cooperation—members support colleagues on issues that may not directly benefit their own constituents with the understanding that they'll receive reciprocal support on their priorities.

Over time, as parties promote a coherent set of policies, they establish a set of legislative accomplishments and a broader reputation that can help all members. This "party brand" or reputation functions as a valuable public good that no single member could create alone. When the party successfully enacts popular policies or is perceived as effective, all members benefit from this collective reputation, gaining electoral advantages. Furthermore, by pooling resources and coordinating messaging, parties enable members to accomplish far more than they could as independent actors, creating incentives for sustained cooperation despite occasional conflicts between party and local interests.

Parties as Organizations

The second role of parties involves their organizational structures—the formal party committees, professional staff, fundraising operations, and activist networks that sustain party activities between elections.

These party organizations fulfill several essential functions:

Candidate recruitment and support: Parties identify and recruit potential candidates, provide campaign resources and expertise, and help coordinate messaging across different races. This support is crucial for maintaining a pipeline of qualified candidates who share the party's broad ideological orientation.

Voter mobilization: Parties invest heavily in identifying supporters, registering new voters, and ensuring their supporters actually vote on Election Day. This mobilization effort helps overcome the collective action problem inherent in voting—while each individual voter has little impact, large-scale turnout is essential for party success.

Information provision: Parties provide voters with simplified information about candidates and issues, reducing the information costs associated with democratic participation. The party label serves as a valuable shortcut, helping voters identify candidates who broadly share their values and policy preferences.

The decentralized structure allows for considerable ideological flexibility within each party. Unlike parliamentary systems where party discipline is enforced through centralized control, American parties function as "big tents" encompassing diverse viewpoints. This flexibility helps parties adapt to different regional contexts and build broader coalitions, though it can also create internal tensions and challenges for maintaining coherent policy agendas.

Parties in the Electorate

The third role of parties consists of ordinary citizens who identify with party labels and support party candidates. This party identification shapes how citizens understand politics, evaluate information, and make voting decisions. Several key aspects characterize parties in the electorate:

Partisan identity: Many Americans develop psychological attachments to parties that function like social identities. These attachments often form early in life through political socialization and tend to remain stable throughout adulthood, though they can shift in response to major political events.

Information processing: Party identification serves as a perceptual filter through which citizens interpret political information. Partisans tend to evaluate co-partisan politicians more favorably and are more receptive to information that confirms their existing partisan predispositions.

Electoral stability: Despite frequent criticisms of parties, partisan loyalties provide remarkable stability to American electoral patterns. Partisan identification is a strong predictor of voting behavior, with close to 90% of self-identified partisans supporting their party's candidates in recent presidential elections.

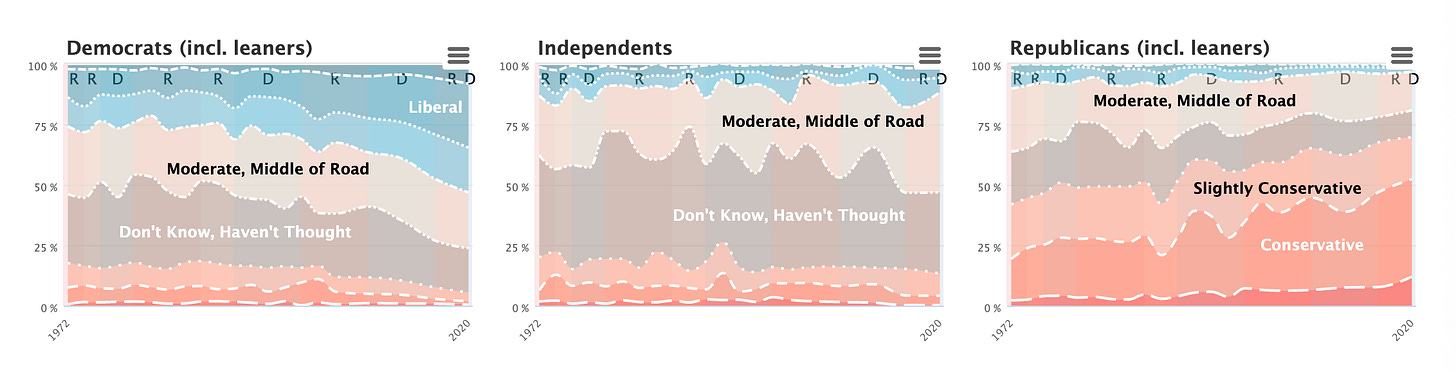

Survey data from the American National Election Studies show that partisan identification has remained relatively stable over time, with most Americans identifying as either Democrats or Republicans (including those who lean toward a party while calling themselves independents). Contrary to popular perception, the proportion of truly independent voters—those without any partisan leaning—has remained relatively small, typically around 10-15% of the electorate. These percentages are even smaller among registered voters, as shown above.

Beyond Party Identification: Moderates and Independents

At the end of the day, most Americans consistently vote for Democrats or Republicans. However, many voters may claim to be "independent" or "moderate." These labels might suggest voters with centrist views who stand between the two parties, but research reveals a more complex reality.

Political scientist Lee Drutman analyzed the ideological positions of self-described moderates, independents, and undecided voters during the 2020 election. Rather than clustering in the ideological middle, these voters were distributed across the ideological spectrum. Some held consistently liberal positions, others consistently conservative views, and many had mixed ideological profiles not neatly captured by either party.

This diversity challenges the assumption that independent or moderate voters necessarily hold "middle of the road" positions between the two parties. Instead, many of these voters hold distinct combinations of views that don't align perfectly with either party's platform. Others may hold ideologically consistent views that would place them clearly within one party's coalition, yet they reject party labels for various reasons—perhaps due to distrust of political institutions, family tradition, or a desire to maintain personal independence in their political identity.

Understanding this complexity helps explain why simply moving to the "center" on issues doesn't necessarily appeal to all independent voters. It also explains why, despite high levels of dissatisfaction with both parties, most Americans continue to vote consistently for one party or the other—their specific policy preferences, even if ideologically mixed, typically lead them to prefer one party over the other when forced to choose in our two-party system.

The Two-Party System

One of the most distinctive features of American democracy is its enduring two-party system. Despite occasional challenges from third parties and independent candidates, Democrats and Republicans have dominated national politics for over 150 years. The primary structural factor reinforcing two-party dominance is the electoral system. The Constitution establishes single-member districts with plurality winners (often called "first-past-the-post" or "winner-take-all" elections) for congressional seats. This arrangement means that only one candidate can win in each district, and that winner need only receive more votes than any other candidate, not an absolute majority.

Political scientist Maurice Duverger observed that single-member plurality systems consistently produce two-party competition. This pattern, known as Duverger's Law, stems from two related mechanisms:

Strategic voting: Voters recognize that supporting candidates with little chance of winning effectively wastes their vote. This creates pressure to support the most viable candidate whose views most closely align with their own, rather than a preferred but non-viable alternative.

Strategic candidates: Politicians and activists similarly recognize that third parties face nearly insurmountable barriers in winner-take-all systems. This creates incentives to work within major parties rather than challenge them from outside. This is why, despite being an Independent, Bernie Sanders has run for the Democratic presidential nomination.

These dynamics create a self-reinforcing equilibrium where two major parties dominate electoral competition. While third parties occasionally emerge to highlight neglected issues, they typically fail to win significant representation and either fade away or see their issues absorbed by one of the major parties.

The Electoral College reinforces these dynamics at the presidential level. Because most states award all their electoral votes to the statewide plurality winner, third-party candidates face even steeper challenges in presidential races than in congressional elections. As a result, presidential elections almost inevitably become two-candidate contests, with third-party candidates either marginalized or serving as "spoilers" that potentially swing elections between the major-party nominees.

Decentralized Party Structure

Despite increasing polarization between the parties, American parties remain remarkably decentralized compared to their counterparts in many other democracies. This decentralization reflects both constitutional structure and historical development.

Federalism and Party Organization

The federal structure of American government creates natural decentralization in party organizations. State and local parties developed before national party committees and retain significant autonomy today. National party committees like the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Republican National Committee (RNC) coordinate national campaigns and establish some broad messaging guidelines, but they cannot force state and local parties or elected officials to adopt their positions and messages.

This decentralization allows parties to adapt to diverse local contexts. Democratic candidates in conservative states may adopt more moderate positions than the national party platform, while Republican candidates in liberal states may distance themselves from certain national party positions. This flexibility helps parties compete across diverse constituencies but can create internal tensions and messaging challenges.

Parties Without Strong Leaders

Unlike parliamentary systems where party leaders exercise strong control over legislative voting, American parties lack clear hierarchical leadership. Even presidents, as de facto party leaders, have limited formal authority over their parties. They cannot remove disloyal members from office, control nomination processes, or enforce voting discipline in Congress.

This dispersed leadership structure creates both opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, it allows for ideological diversity within parties, potentially broadening their electoral appeal. On the other, it creates space for intra-party factions to challenge party orthodoxy and leadership. The absence of strong centralized control explains why American parties often appear less cohesive than their counterparts in parliamentary systems.

Party Polarization and Sorting

Perhaps the most significant change in American party politics over recent decades has been the increasing polarization between the two major parties. This polarization manifests in several ways:

Ideological Sorting

In the mid-twentieth century, both major parties contained ideologically diverse factions. Conservative Democrats (particularly from the South) often aligned with Republicans on issues like civil rights while liberal Republicans (mainly from the Northeast) sometimes voted with Democrats on social welfare policies.

This ideological diversity has largely disappeared through a process political scientists call partisan sorting—the alignment of ideological and partisan identities. Today, the Democratic Party consists primarily of liberals, while the Republican Party consists primarily of conservatives. This sorting reflects both elite-level changes as politicians have staked out clearer ideological positions and mass-level changes as voters have aligned their partisanship with their ideological preferences.

Survey data from the American National Election Studies illustrates this trend clearly. The parties have become more more ideologically sorted than they were in the 1970s, which has created more ideologically cohesive parties but has also sharpened partisan conflict and reduced opportunities for bipartisan cooperation.

Demographic Sorting

Beyond ideology, parties have increasingly sorted along demographic lines, creating distinct social coalitions:

Gender: Women have become increasingly Democratic in their voting patterns, while men lean Republican, creating what political analysts call the "gender gap."

Education: College-educated voters have shifted toward the Democratic Party, while non-college-educated voters, particularly whites without college degrees, have moved toward the Republican Party.

Urban-rural divide: Urban areas have become Democratic strongholds, while rural areas consistently support Republicans, with suburbs as contested battlegrounds.

Race and ethnicity: Racial minorities, particularly Black and Hispanic voters, predominantly support Democrats, though there is significant variation within these broad categories and potential shifts following the 2024 election.

These demographic patterns create distinct social worlds associated with each party, potentially reinforcing polarization through social identity mechanisms. When partisanship aligns with other important identities like race, religion, or location, it becomes more emotionally charged and resistant to change.

Conclusion: Parties in a Polarized Age

The paradox with which we began—widespread criticism of parties alongside their continued dominance—reflects the essential role parties play in democratic governance. Despite their unpopularity, parties provide structure to political conflict, organize electoral competition, and enable collective action in government. The question is not whether we will have parties, but what kind of parties will best serve democratic governance.

Contemporary American parties face several interconnected challenges:

Representation challenges: As parties sort ideologically and demographically, they may struggle to represent the full diversity of American perspectives. When parties become social identities rather than just policy coalitions, they may prioritize group loyalty over responsive governance.

Governing challenges: Polarized parties struggle to find common ground, particularly during periods of divided government. The constitutional system of checks and balances assumes some willingness to compromise across institutional boundaries, which becomes difficult when party identity overrides institutional loyalty.

Legitimacy challenges: When citizens view the opposing party not just as wrong but as a fundamental threat to American values, it becomes difficult to maintain the shared commitment to democratic norms necessary for stable governance. Accepting the legitimacy of opposition party victories becomes particularly challenging in this environment.

Although these challenges may seem insurmountable today, parties will inevitably adapt. Throughout American history, parties have reinvented themselves in response to new challenges, absorbing new constituencies and issues while maintaining their institutional continuity. The current period of polarization and sorting may eventually give way to new alignments that better accommodate the diverse perspectives within American society.

In the meantime, understanding how parties function helps citizens engage more effectively with the political system. Rather than lamenting the existence of parties or hoping for their demise, democratic citizens might focus on making parties more responsive to public concerns and better able to deliver effective governance despite constitutional constraints. The framers may have hoped to avoid parties, but generations of political experience suggest that democracy requires them, just as it requires citizens to hold them accountable.

Key Terms

Political parties: Coalitions of politicians, interest groups, activists, and voters who seek to control government by winning elections.

Duverger's Law: The principle that single-member district plurality electoral systems tend to produce two-party systems.

Partisan sorting: The process by which ideological views and partisan identification have become increasingly aligned.

Party in government: Elected officials who represent their party in governmental institutions.

Party organization: The formal structures and networks that maintain party operations between elections.

Party in the electorate: Ordinary citizens who identify with and support a political party.