Obviously, My Political Opinions Are Correct. So Why Doesn’t Everyone Agree with Me?

How personal, social, and political factors shape public opinion (yes, even yours!).

Learning Objectives

Understand what public opinion is and its significance in American democracy.

Identify the various influences on public opinion, including personal, social, and political factors.

Analyze how and why public opinion changes over time.

Public Opinion in American Democracy

In previous chapters, we examined the institutions of American government—Congress, the presidency, the courts, and the bureaucracy. Each of these institutions operates within a complex system of checks and balances designed to distribute power and promote deliberation. Yet in a representative democracy, these institutions don't exist in isolation. They are designed to be responsive to the will of the people.

This relationship between institutions and citizens raises fundamental questions about democratic governance: How do elected officials know what policies citizens want? How do citizens form opinions about complex political issues? To what extent should representatives follow public preferences versus exercising independent judgment? These questions lie at the heart of democratic theory and practice.

Public opinion serves as the crucial link between citizens and their government. Political Scientist Harold Lasswell famously defined politics as "who gets what, when, and how." Public opinion influences each element of this definition by shaping electoral outcomes, policy priorities, and implementation strategies. Understanding where public opinion comes from, as well as how public opinion changes, is essential to understanding American democracy.

This chapter explores the nature of public opinion, examining how it develops from various personal, social, and political influences. We'll investigate how political actors attempt to shape public views while simultaneously responding to them. Finally, we'll consider how and when public opinion changes.

What Is Public Opinion?

Defining Public Opinion

Public opinion refers to citizens' attitudes about political issues, personalities, institutions, and events. While we often think of public opinion primarily in terms of policy preferences—support for or opposition to specific proposals like tax cuts or environmental regulations—it encompasses a much broader range of attitudes.

These attitudes include:

Evaluations of political figures, such as presidential approval ratings.

Trust in institutions, including Congress, the courts, and the media.

Policy preferences on specific issues like immigration, health care, and climate change.

Political values such as freedom, equality, and security.

Ideological orientations that organize political thinking.

Partisan attachments that shape electoral behavior.

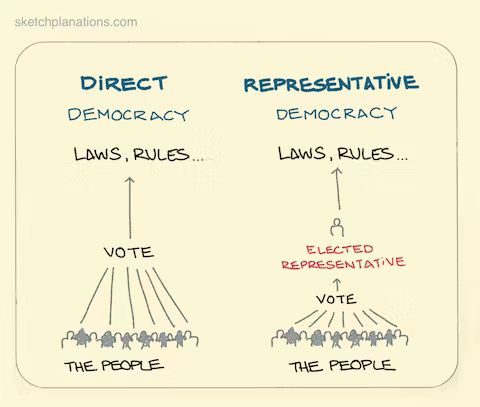

Public opinion forms the foundation of democratic governance through what political scientists call a principal-agent relationship. In this framework, citizens (principals) delegate authority to elected representatives (agents) who are expected to act on the public's behalf. Regular elections serve as accountability mechanisms, allowing citizens to reward responsive representatives with continued office and punish those who ignore public preferences.

This relationship creates a fundamental dynamic in democratic systems: representatives must be sufficiently responsive to public opinion to secure reelection while still exercising independent judgment on complex issues. Representatives who completely ignore public sentiment risk electoral defeat, creating strong incentives for at least some level of responsiveness. Even unelected officials, such as federal judges, must consider public views to maintain institutional legitimacy.

At the same time, representatives may seek to shape public opinion rather than merely respond to it. By giving speeches, holding town halls, or appearing in media, politicians attempt to lead public opinion toward their preferred policies. This two-way relationship between opinion and leadership creates a complex dance of influence that lies at the heart of democratic representation.

Expressing Public Opinion

Citizens express their political opinions through numerous channels, creating a complex information environment that politicians must navigate. The most visible forms of expression include:

Polling and surveys that systematically measure attitudes across the population.

Voting behavior in elections and referendums.

Direct communication with elected officials through calls, letters, and town hall meetings.

Protest activities such as demonstrations, marches, and petitions.

Social media engagement including posts, comments, and shares.

Campaign participation through donations, volunteering, and lawn signs.

Media consumption that signals interest in particular issues.

Each of these expressions provides different information about public preferences. Electoral results indicate overall support for candidates and parties but reveal little about specific policy positions. Polls offer more precise measurements of issue attitudes but may fail to capture intensity of feeling or willingness to act. Protests demonstrate strong commitment from participants but may not represent broader public sentiment.

Political leaders therefore face the challenging task of aggregating and interpreting these diverse signals to determine what "the public" wants. This task is complicated by the fact that different segments of the public often hold contradictory views, forcing leaders to decide which constituencies to prioritize.

Sources of Public Opinion: Personal Factors

Public opinion doesn't form in a vacuum. Individual attitudes emerge from complex interactions between personal characteristics, social environments, and political contexts. Understanding these sources helps explain why people hold the views they do and how those views might change over time.

Self-Interest

Perhaps the most intuitive source of political attitudes is self-interest—people support policies they believe will benefit them and oppose those they expect will harm them. Economic interests often drive political preferences. For example, higher-income individuals typically favor lower tax rates while those with fewer resources may support expanded social programs.

Self-interest extends beyond economic considerations to encompass various dimensions of well-being. Parents may prioritize education policies, senior citizens may focus on healthcare and retirement security, and residents of coastal areas may care more about climate change and flood insurance.

However, the relationship between self-interest and political attitudes is more complicated than it first appears. In his influential book What's the Matter with Kansas?, Thomas Frank questioned why many working-class voters support conservative economic policies that appear contrary to their economic interests. Critics responded that these voters may prioritize other dimensions of self-interest—such as cultural, religious, or moral concerns—over immediate economic advantage.

The debate highlights an important insight: people define their interests in diverse ways, and what appears irrational from one perspective may reflect legitimate prioritization of different values. Cultural or moral self-interest can be just as powerful a motivator as economic self-interest.

Values and Morals

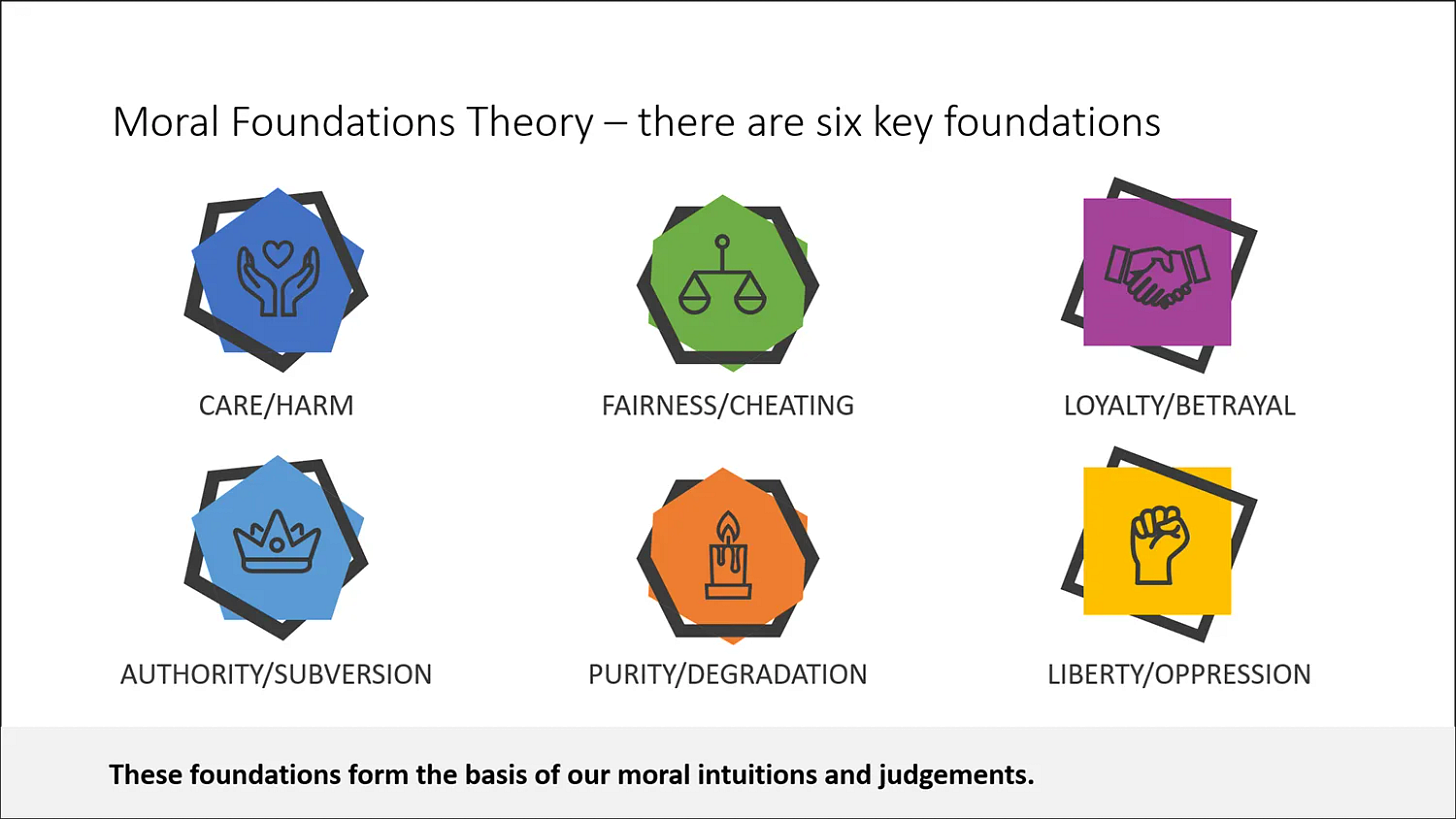

Core values about justice, fairness, liberty, and morality profoundly shape political attitudes. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt's research on moral foundations suggests that liberals and conservatives emphasize different moral values when forming political judgments. For example, liberals tend to prioritize care and fairness, while conservatives place more emphasis on loyalty, authority, and sanctity.

These divergent moral priorities help explain why different people can examine the same situation and reach opposite conclusions. Consider debates over abortion rights: those who emphasize individual autonomy tend to support abortion access, while those who prioritize sanctity of life typically oppose it. Both positions reflect sincere moral convictions that aren't easily reconciled through compromise.

Value-based disagreements present particular challenges for democratic governance because they resist the bargaining and splitting-the-difference approaches that work for distributional conflicts. When issues are framed in absolute moral terms, finding middle ground becomes extremely difficult.

Information and Political Knowledge

Access to information and political knowledge significantly affects opinion formation. Better-informed citizens typically develop more consistent and stable political attitudes because they can connect specific policies to their underlying values and interests.

However, most Americans possess limited political knowledge. In a 2023 Pew Research Center survey, only two-thirds of respondents could identify which party controlled the House, and fewer than half knew how long a senator's term lasts. This knowledge gap reflects rational behavior rather than civic negligence—most people have busy lives filled with work, family, and social commitments that take priority over monitoring political developments that they have minimal ability to influence.

Limited knowledge affects how people form and express opinions. When asked about unfamiliar issues, many respondents will construct "top-of-the-head" opinions rather than admitting uncertainty. These improvised views tend to be inconsistent and unstable, shifting in response to how questions are framed or which considerations are most accessible at the moment of response.

This dynamic has significant implications for democratic governance. First, it suggests that much of what polling captures isn't deeply held conviction but rather ephemeral reactions constructed on the spot. When pollsters ask about complex policy issues like international trade agreements or financial regulations, many respondents formulate opinions despite knowing little about the topics.

Sources of Public Opinion: Social Factors

While personal characteristics provide one foundation for political attitudes, social contexts fundamentally shape how those attitudes develop and express themselves. People don't form opinions in isolation but rather through interactions with family, friends, media, and broader cultural influences.

Political Socialization

Political socialization refers to the process through which people develop political values, beliefs, and identities. This process begins in childhood and continues throughout life, with early experiences often having lasting impacts on political orientation. Family environments provide the initial context for political socialization. Parents transmit political values both explicitly, through direct discussion of politics, and implicitly, through modeling behavior and establishing moral frameworks.

The time period in which people come of age politically also shapes their lifetime attitudes. Ghitza, Gelman and Auerbach’s research demonstrates that political events experienced during teenage and early adult years have disproportionate influence on later political behavior. Those who reached political maturity during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations show more liberal voting patterns than those who came of age during the conservative Reagan presidency, reflecting the different political environments of those eras.

These generational patterns help explain why political change sometimes occurs gradually, through population replacement rather than through individuals changing their minds. As older cohorts exit the electorate and younger ones enter, the overall distribution of opinion shifts accordingly.

Media and Cultural Influences

Mass media and popular culture significantly influence political attitudes by framing issues, highlighting particular aspects of politics, and normalizing certain perspectives while marginalizing others.

News media affect public opinion through both informational and framing effects. Informational effects occur when media outlets provide facts that change how people understand issues. Framing effects occur when media coverage emphasizes certain aspects of issues while downplaying others, influencing how audiences interpret events.

Entertainment media also shape political attitudes, often in subtle ways. Television programs, movies, and music establish cultural reference points that inform how people think about political institutions and issues. For example, political dramas like The West Wing or Veep present contrasting views of presidential leadership that may influence viewers' expectations about executive power, even if they don't consciously connect entertainment to their political attitudes.

These cultural influences can be particularly powerful because they reach people who might avoid explicitly political content. A person who never watches cable news might still absorb political messages from popular entertainment, often without the critical filtering applied to overtly political information.

Opinion Leaders

Most citizens don't independently research every political issue but instead rely on opinion leaders—trusted figures who provide guidance on political matters. These leaders might include political commentators, religious authorities, community organizers, or simply knowledgeable friends and family members.

Opinion leaders serve as intermediaries between complex political information and ordinary citizens, simplifying issues and connecting them to existing values and priorities. This process, which communication scholars call the "two-step flow of information," allows people to develop opinions without investing substantial time in political research.

This reliance on opinion leaders reflects an efficient division of labor rather than intellectual laziness. Politics encompasses countless complex issues, and developing informed views on each would require enormous time investment. By identifying trusted sources who share their fundamental values, people can "outsource" much of this cognitive work while still developing coherent political perspectives.

However, this efficiency comes with potential drawbacks. If people select opinion leaders who merely reinforce existing views, they may become insulated from alternative perspectives, contributing to polarization. Additionally, opinion leaders may themselves be misinformed or strategic in their presentation of issues, potentially transmitting inaccurate information to their followers.

Sources of Public Opinion: Political Factors

Beyond personal and social influences, the structure of the political system itself shapes how people form and express opinions. Partisanship and ideology provide organizing frameworks that help citizens make sense of complex political information and develop coherent attitudes across diverse issues.

Partisanship

Party identification represents one of the most powerful influences on political attitudes. Rather than independently evaluating each policy or candidate, most citizens use their partisan identity as a shortcut for determining what to believe and how to vote.

Political scientists debate whether partisanship functions primarily as a social identity (similar to religious or ethnic identity) or as a "running tally" of policy evaluations. The identity perspective emphasizes psychological attachment and group loyalty, arguing that partisan affiliations form early in life, remain stable over time, and serve as powerful filters through which people interpret political information. When partisanship functions as an identity, supporting one's party becomes about defending the group rather than evaluating policy outcomes. The running tally model suggests citizens support parties that deliver preferred policies, comparing their policy preferences to party performance and adjusting their partisan loyalties accordingly. This perspective views voters as more rational calculators who might switch parties if their current party repeatedly fails to deliver desired outcomes.

Evidence suggests elements of both theories apply. Party identification shows remarkable stability over time, consistent with an identity perspective. Yet major policy shifts or performance failures can prompt partisan realignment, suggesting some policy-based calculation.

Regardless of its precise nature, partisanship profoundly shapes how people interpret political information. Identical economic conditions will be viewed more favorably when one's own party holds the presidency, as illustrated by dramatic shifts in economic perceptions when presidential administrations change parties.

This partisan filtering of reality creates challenges for democratic accountability. If voters evaluate incumbents based on partisan loyalty rather than objective performance, elected officials face reduced incentives to deliver effective governance.

Ideology

While partisanship describes political team membership, ideology represents organized attitudes about how government should work, tied to underlying principles. The American political spectrum revolves primarily around conservative and liberal ideologies, though libertarian and populist perspectives also influence political discourse.

Liberal ideology generally supports more active government involvement in the economy, stronger social service programs, and expansive civil rights protections. Conservative ideology typically advocates limited government, free-market economics, and traditional social values. These ideological frameworks help citizens organize their thinking across diverse issues.

According to Gallup surveys, Americans have increasingly embraced ideological labels over time. The percentage identifying as liberal has grown steadily since the 1990s, while conservative identification has remained relatively stable and moderate identification has declined.

Ideological consistency has also increased, with fewer Americans holding mixed liberal and conservative positions across different issues. This sorting process strengthens the relationship between ideology and partisanship, as liberals increasingly identify as Democrats and conservatives as Republicans.

However, these ideological categories have evolved significantly over time and often contain internal contradictions. Historically, the parties have even switched positions on many issues. What we now consider "liberal" positions were once associated with Republicans, while Democrats were once the party of conservative values, particularly in the South. This ideological transformation accelerated during the Great Depression, when Franklin Roosevelt's Democratic administration embraced activist government while Republicans opposed government intervention.

In practice, many Americans hold ideologically inconsistent views. For example, conservatives who favor limited government may simultaneously support aggressive military spending and restrictions on certain personal freedoms based on religious values. Similarly, liberals who advocate government regulation of businesses may oppose government surveillance or restrictions on speech. These inconsistencies arise because ideological labels represent simplified frameworks rather than logically coherent philosophical systems.

For political leaders, these ideological patterns create both constraints and opportunities. Clearer ideological divisions make coalition-building more difficult across party lines but can strengthen within-party cohesion, potentially facilitating more unified action when a single party controls government.

How Public Opinion Changes

While some aspects of public opinion—particularly partisan identities and core values—remain relatively stable throughout adulthood, issue attitudes can shift dramatically in response to changing contexts. Understanding these dynamics helps explain why public opinion sometimes appears contradictory or unpredictable.

Changes in the Political Agenda and Party Positions

When political leaders highlight particular issues or shift party positions, public attitudes often follow. This process operates through several mechanisms:

First, elite discourse provides cues that help citizens form opinions on unfamiliar topics. When party leaders adopt clear positions, their supporters tend to align their views accordingly, particularly on technical issues where they lack independent expertise.

Second, political attention elevates certain considerations while suppressing others. For example, discussing immigration in terms of economic impacts versus cultural integration activates different values and concerns, potentially shifting overall support.

Same-sex marriage illustrates how rapidly opinion can change when political and cultural leaders shift positions. In the 1990s, approximately 70% of Americans opposed same-sex marriage. By the 2020s, about 70% supported it—a remarkable reversal in just a few decades. This transformation reflected changing elite positions, increased visibility of LGBTQ individuals in media and public life, and generational replacement as younger, more supportive cohorts entered the electorate.

Such examples demonstrate that public opinion, rather than being fixed, responds dynamically to changing political environments. Leaders don't simply follow public opinion but actively shape it through their rhetoric and policy priorities.

Issue Importance

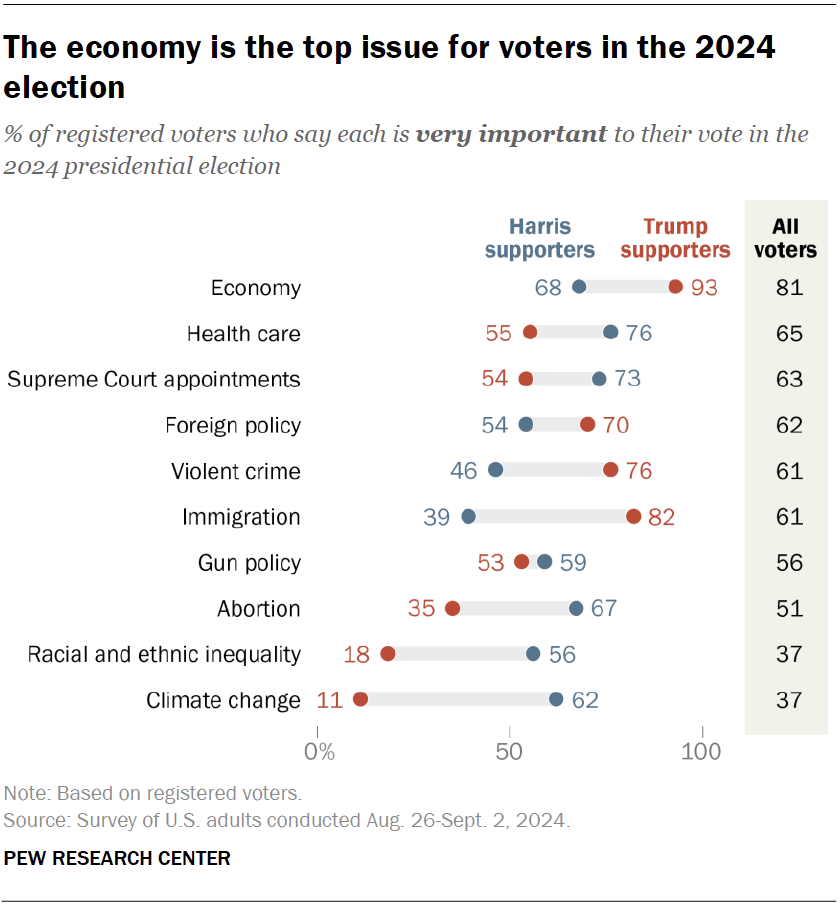

Not all opinions carry equal weight in political decision-making. Issue salience—the importance citizens attach to particular topics—significantly influences both voting behavior and policy responsiveness.

Politicians strategically emphasize issues where their positions align with public preferences or where their party is favored. For example, if Republicans perform better on economic issues while Democrats have advantages on healthcare, each party may attempt to make their stronger issues more salient during campaigns.

Issue importance also affects how citizens evaluate candidates and incumbents. Voters who care deeply about a few issues may support candidates who share their positions on those concerns, even if they disagree on other matters. This dynamic creates opportunities for minority positions to gain representation when they're held with high intensity by a dedicated constituency.

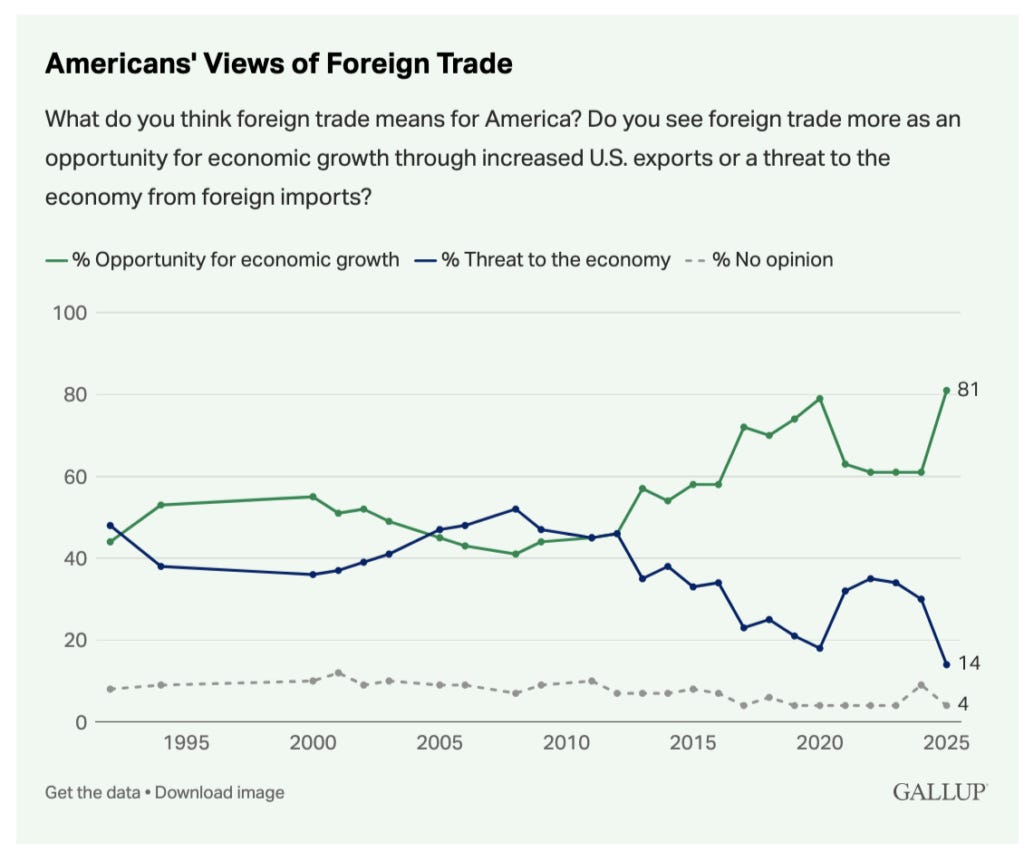

Thermostatic Public Opinion

Think of public opinion like a thermostat in your home. When your house gets too hot, the air conditioning kicks in to cool it down. When it gets too cold, the heater turns on to warm it up. The goal is to maintain a comfortable middle temperature.

Public opinion works in a similar way. When government policies move in one direction—either too liberal or too conservative—public attitudes often shift in the opposite direction to balance things out. This is called the "thermostatic" effect.

For example, when President Trump took office and implemented stricter immigration policies, public support for those tough policies declined. Later, when President Biden adopted more lenient immigration approaches, support for stricter border security increased again. Now that Trump is in office, immigration attitudes have flipped back. The public is essentially "correcting" what it perceived as policy moving too far in either direction.

You can also see this pattern in attitudes toward foreign trade. Although most Americans already saw trade positively, attitudes became sharply more positive once Trump took office.

This balancing effect could explain why presidents often see their party lose seats in midterm elections. After winning power, a president's party typically pursues its agenda enthusiastically—whether liberal or conservative. This strong policy movement in one direction leads to a public opinion shift in the opposite direction, contributing to electoral losses for the president's party in the next election. This pattern suggests that most Americans have a status quo bias and prefer moderate policies to dramatic shifts in either direction.

The Limited Role of Misinformation

Many are concerned about misinformation—false or misleading information that supposedly distorts public opinion and undermines democratic decision-making. While factual misunderstanding certainly exists, research suggests its impact on political attitudes may be more limited than commonly assumed.

Research shows that simply correcting factual errors doesn't usually change people's political attitudes. In one study, Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin (2018) asked people to guess how many immigrants live in the United States. Some people greatly overestimated the number. The researchers then told half of these people the correct, lower number. Did learning the truth change their views about immigration? Not really.

Those who initially opposed immigration still opposed it even after learning the real numbers. Similarly, people who supported immigration continued to support it even when they learned the immigrant population was larger than they thought. This pattern suggests something important: the causal arrow often runs from attitudes to beliefs rather than the reverse. People develop policy preferences based on values, identities, and interests, then adopt factual beliefs that support those preferences. Simply correcting misconceptions therefore has minimal impact on the underlying attitudes.

This dynamic doesn't mean factual information is irrelevant, but it does suggest limits to a model of public opinion where we assume citizens would reach consensus if only they shared the same underlying facts. In reality, political disagreements typically stem from different values and priorities rather than factual misunderstandings.

Public Opinion and Democracy

Democracy rests on the principle that government should reflect the will of the people. Yet translating public preferences into policy involves complex processes that often produce imperfect representation. Understanding these challenges helps clarify the relationship between opinion and governance in democratic systems.

The Delegate vs. Trustee Debate

Political scientists have long debated whether representatives should act as delegates, who directly translate constituent preferences into votes, or as trustees, who exercise independent judgment and make decisions that they think will be in the public interest. This tension reflects competing conceptions of representation in democratic theory.

The delegate model emphasizes responsiveness to constituent wishes, treating representatives as vehicles for transmitting public preferences into policy. This approach maximizes democratic input but may sacrifice deliberation and expertise in decision-making.

The trustee model emphasizes representatives' responsibility to exercise informed judgment rather than simply following public opinion. This approach values deliberation and expertise but potentially compromises democratic control.

Most representatives adopt hybrid approaches depending on issues and contexts. On highly salient issues where constituents hold strong views, representatives may follow constituency opinion closely. On technical matters where public attention is limited, they may exercise greater independent judgment, often influenced by party leadership, interest groups, and policy experts.

This hybrid approach balances competing democratic values—popular control and deliberative decision-making—but creates inevitable tensions in representation. Citizens who expect pure delegate representation may feel betrayed when representatives exercise independent judgment, while those who value expertise may criticize representatives who simply follow popular sentiment.

Challenges to Democratic Responsiveness

Several structural features of American democracy complicate the relationship between public opinion and policy outcomes:

Constitutional constraints intentionally limit majoritarian control, protecting minority rights and establishing guardrails around democratic decision-making.

Federalism divides authority across levels of government, creating multiple points where policy can diverge from national majority preferences.

Checks and balances require agreement across institutions with different constituencies and electoral cycles, making coherent policy difficult even when public opinion is clear.

Electoral systems based on geographic districts rather than proportional representation can produce legislative majorities that don't reflect overall popular sentiment.

These features reflect deliberate design choices by the framers, who sought to balance democratic responsiveness with protection against majority tyranny and hasty decision-making. The resulting system produces greater policy stability but sometimes at the cost of direct majoritarian control.

Conclusion: Public Opinion in a Polarized Age

Public opinion plays an essential role in democratic governance, providing guidance for representatives and establishing boundaries for acceptable policy. When officials stray too far from public preferences over extended periods, electoral mechanisms eventually produce course corrections.

Yet the relationship between opinion and governance has grown increasingly complex in an era of partisan polarization and fragmented media environments. Partisan sorting has created more homogeneous districts where representatives face greater pressure from primary elections than general elections, potentially reducing responsiveness to moderate voices. Media fragmentation allows citizens to consume information that reinforces existing views rather than challenging them, potentially hardening polarization.

Despite these challenges, public opinion remains fundamental to democratic legitimacy. Through voting, communication with representatives, and various forms of political participation, citizens continue to influence government action. While the translation from opinion to policy is neither simple nor automatic, the public's voice remains an essential force in American democracy.

Understanding how public opinion forms and changes helps citizens navigate an increasingly complex political environment. By recognizing the personal, social, and political factors that shape their own views and those of others, Americans can engage more effectively in democratic discourse and hold representatives accountable for responding to public preferences.

Key Terms

Public opinion: Citizens' attitudes about political issues, personalities, institutions, and events.

Political socialization: The process through which people develop political values, beliefs, and identities.

Ideology: Organized attitudes about how government should work, tied to underlying principles.

Liberalism: An ideological orientation that generally favors a more active role for government in addressing social and economic inequalities, supports expansive civil rights protections, and embraces social change.

Conservatism: An ideological orientation that generally favors limited government involvement in the economy, traditional social values, and gradual rather than rapid social change.

Issue salience: The importance citizens attach to particular topics.

Thermostatic public opinion: The tendency of public attitudes to shift against the ideological direction of current policy.

Opinion leaders: Trusted figures who provide information, cues, and guidance on political matters.