Learning Objectives

Understand the constitutional design of Congress and how its bicameral structure shapes legislative behavior.

Analyze the different types of representation and how they manifest in congressional practice.

Identify how electoral systems and rules influence who serves in Congress and how they behave.

Evaluate how Congress solves collective action problems through committees, parties, and procedural rules.

Explain how the legislative process works in theory and in contemporary practice.

Introduction: The Rational Actor in a Collective Institution

When analyzing congressional behavior—whether it's a budget standoff, a leadership election, or routine lawmaking—political scientists begin with a fundamental principle: all political behavior has a purpose (Lowi et al).

As political scientist Richard Fenno observed in his influential 1973 study, members of Congress consistently pursue three primary objectives:

Winning re-election.

Creating what they consider "good" public policy.

Gaining influence within Congress itself.

Far from being random or irrational, the complex drama that unfolds on Capitol Hill reflects strategic calculations by rational actors operating within institutional constraints.

This framework helps explain seemingly puzzling congressional behavior. For example, when a representative votes against a budget bill they know will eventually pass, they may be signaling fiscal restraint to voters back home (re-election goal), expressing genuine concern about deficit spending (policy goal), or positioning themselves for better committee assignments by demonstrating that they won’t work across the aisle (influence goal). What might appear as dysfunction to outside observers often represents rational responses to the incentives created by electoral systems, institutional rules, and constituent1 demands.

Yet individual goals alone cannot explain congressional behavior. As Frances Lee's research demonstrates, members also consider their party's collective interests, recognizing that achieving personal goals becomes easier when their party holds the majority and maintains a positive reputation. This creates a complex strategic environment where representatives must balance individual ambitions against partisan considerations and institutional responsibilities.

The tension between individual goals and collective action lies at the heart of congressional politics. While 535 members each pursue their own objectives, Congress as an institution must somehow coordinate their actions to fulfill its constitutional responsibilities. Here, we examine how Congress's constitutional design, electoral systems, and internal organization help resolve these tensions, enabling effective governance despite the inherent challenges of collective decision-making in a large, diverse legislative body.

The Constitutional Design: House and Senate

From Constitutional Convention to Contemporary Congress

The Constitution's framers deliberated extensively about legislative design, seeking to create an institution that would be both responsive to the people and capable of thoughtful deliberation. Their solution—a bicameral legislature with chambers of different sizes, constituencies, and electoral timetables—reflected both principled judgments about representation and practical compromises among competing interests.

The legislative branch received pride of place in the constitutional order. Article I, the longest section of the Constitution, precedes the articles establishing the executive and judicial branches, reflecting the framers' vision of Congress as the central institution of government. The bicameral structure they created balanced competing principles of representation while creating a system of internal checks that complemented the broader separation of powers.

The House: Proximity to the People

The House of Representatives was designed as the legislative chamber closest to the American people, embodying the democratic principle that government should reflect popular will. Key features of the House include:

Population-based representation: The 435 members each represent roughly 770,000 constituents (significantly more than the original 33,000 per district in 1790).

Two-year terms: All representatives face election simultaneously, creating constant electoral pressure.

Eligibility requirements: Members must be U.S. citizens for at least seven years and at least 25 years old.

Powers: Exclusive authority to initiate revenue bills and the power to impeach federal officials.

The constitutional framers designed the House to be responsive to shifting public sentiment. The relatively short two-year terms ensure that representatives remain accountable to their constituents, while the population-based apportionment creates a direct link between population centers and legislative influence.

This responsiveness has trade-offs. Representatives must constantly balance governing responsibilities with electoral considerations, potentially prioritizing short-term popularity over long-term policy solutions. The frequency of elections also forces members to devote substantial time to fundraising and campaign activities rather than legislative work.

The Senate: Deliberative Stability

The Senate presents a stark contrast to the House's design:

State-based representation: Each state receives two senators regardless of population, creating a body of 100 members.

Six-year terms: Only one-third of senators face election in any given cycle.

Original selection by state legislatures: Until the 17th Amendment (1913), senators were chosen by state legislatures rather than direct popular vote.

Eligibility requirements: Members must be U.S. citizens for at least nine years and at least 30 years old.

Powers: Exclusive authority to confirm presidential appointments and ratify treaties.

This structure reflects the framers' desire for a more deliberative, less reactive body that could resist momentary passions. The longer terms and staggered elections were intended to insulate senators from immediate public pressure, allowing them to consider long-term consequences and take potentially unpopular but necessary actions. As James Madison explained in Federalist No. 63, the Senate would provide "the cool and deliberate sense of the community" to defend against the possibility that when the public, swayed by "some irregular passion, or some illicit advantage, or misled by the artful misrepresentations of interested men, may call for measures which they themselves will afterwards be the most ready to lament and condemn.”

The equal representation of states—giving Wyoming and California the same number of senators despite their vast population difference—demonstrates the compromise between population-based democracy and state-based federalism that characterizes the American system. This design gives smaller, rural states disproportionate influence in the Senate, creating policy consequences that continue to shape American politics.

Comparing House and Senate Leadership

The different sizes and electoral structures of the two chambers have produced distinct leadership models:

House Leadership:

The Speaker of the House serves as both chamber leader and party leader.

Majority control is strong, with the majority party controlling committee assignments, the legislative agenda, and procedural rules through the Rules Committee.

Minority influence is limited, with few opportunities to shape legislation.

Senate Leadership:

The Vice President constitutionally presides but has limited practical influence.

The Majority Leader coordinates the agenda but has fewer formal powers than the Speaker.

Unanimous consent agreements and the filibuster give individual senators and the minority party significant influence.

Objections from even a single senator can delay proceedings.

Minority party has greater influence in the legislative process than in the House.

These leadership differences reflect the chambers' different sizes and historical development. The large membership of the House necessitated more centralized authority and stricter procedural rules to function effectively. The Senate's smaller size allowed for more individualistic traditions like unlimited debate and unanimous consent agreements.

Unlike parliamentary systems where the executive emerges from the legislature, the American presidential system creates separate electoral pathways for the executive and legislative branches. This separation often results in divided government—where different parties control different branches—creating additional complexity in the lawmaking process.

Congressional Elections and Districts

The Evolution of Congressional Districts

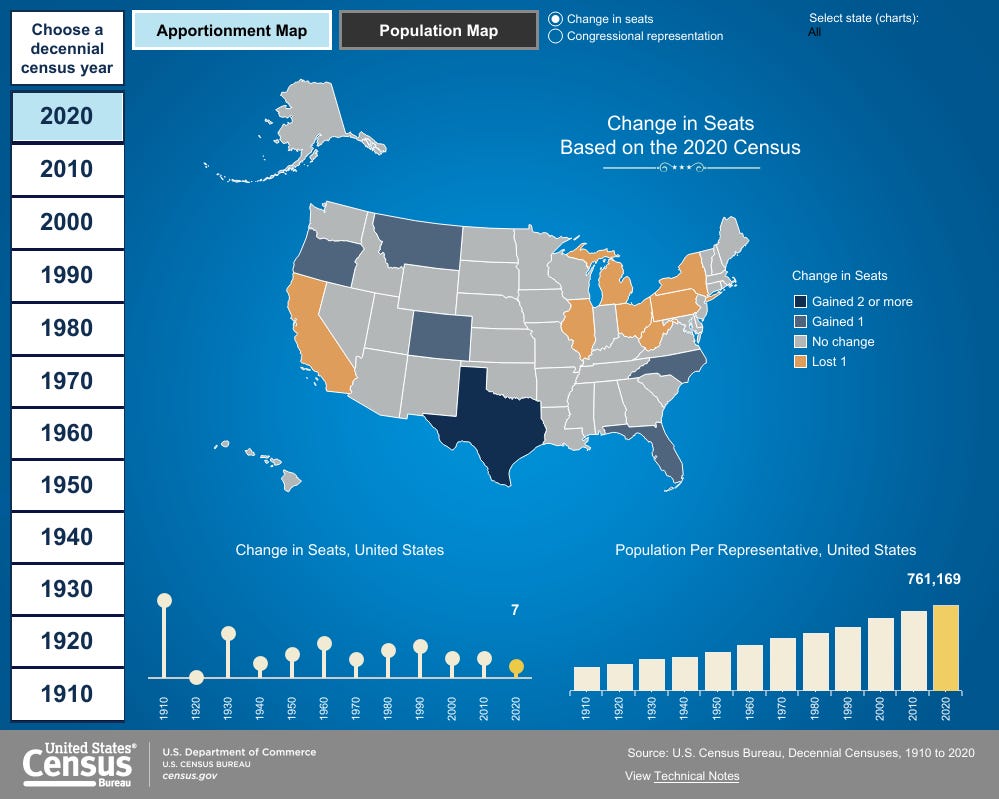

The composition of the House of Representatives has changed significantly since its inception:

In 1792, the House had 105 seats, with each representative serving approximately 33,000 people.

As the U.S. population grew, seats were added until 1911, when Congress increased the size of the House to 435 members.

The House membership was permanently capped at 435 by the Reapportionment Act of 1929.

Today, each representative serves approximately 761,000 people—over 23 times the original constituency size.

This cap on House membership has important consequences. Rather than adding new seats as the population grows, states gain or lose representation based on population shifts measured in the decennial census. Over time, this has led to substantial regional redistribution of political power:

Western and Southern states have generally gained seats since 1950.

Midwestern and Northeastern states have typically lost seats as population has shifted.

The cap also affects coordination and collective action within the chamber. While a larger House might be more representative, it would also face greater challenges in organizing and deliberating effectively. The fixed size represents a compromise between representative capacity and institutional functionality.

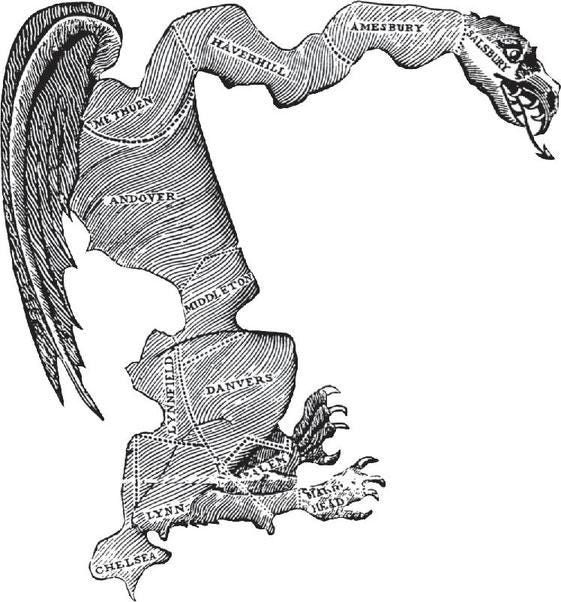

Gerrymandering and District Design

Although federal law determines how many seats each state receives, state governments control the actual drawing of district boundaries. This process, known as redistricting, occurs after each census and significantly affects representation and electoral outcomes.

Gerrymandering—the practice of drawing district lines to advantage particular parties or groups—has a long history in American politics, dating back to Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry's salamander-shaped district in 1812. Modern gerrymandering employs sophisticated mapping software and detailed demographic data to maximize partisan advantage through two primary strategies:

"Packing" opposition voters into a few districts where they win by overwhelming margins.

"Cracking" opposition voters across multiple districts where they constitute a large minority but can't win.

While the Supreme Court has not prohibited partisan gerrymandering under the Constitution, it has restricted racial gerrymandering that discriminates against minority populations. Under the Voting Rights Act and subsequent court decisions, states must consider racial representation when drawing districts, sometimes requiring the creation of "majority-minority" districts where historically underrepresented groups can elect their preferred candidates.

Some states have attempted to address partisan gerrymandering through alternative approaches:

Independent redistricting commissions (as in California).

Bipartisan commissions with equal party representation.

Requirements for geographic compactness and respect for existing political boundaries.

The persistence of gerrymandering illustrates how electoral rules and procedures—not just voter preferences—shape congressional outcomes and contribute to partisan polarization. If a party is structurally advantaged and is unlikely to lose office, then they have much weaker incentives to be responsive to their constituents.

Electoral Systems and Representation

The American electoral system has several distinctive features that affect congressional representation:

Single-member districts: Each district elects just one representative.

Plurality voting ("first-past-the-post"): Whoever receives the most votes wins, even without a majority.

These two features have significant consequences. In a district like California's 50th, where Democrat Scott Peters won the 2024 election with 64% of the vote over Republican Peter Bono's 36%, over a third of voters are represented by someone they voted against. Unlike proportional systems used in many democracies, the American system doesn't guarantee minority parties representation proportional to their vote share.

Nationalization of Congressional Elections

Historically, many members of Congress won in districts that voted for the opposite party in presidential elections. These "split-ticket" outcomes created incentives for bipartisanship and moderation, as representatives needed to appeal to voters from both parties.

In recent decades, however, congressional elections have become increasingly "nationalized"—aligned with presidential voting patterns. As voters have sorted into more ideologically consistent partisan camps, split-ticket voting has declined dramatically. The result is fewer representatives who win in districts that favor the opposite party president.

This nationalization has important implications:

Representatives face less electoral incentive to work across party lines.

National party brands and presidential politics increasingly influence local congressional races.

When lawmakers are incentivized to focus on national issues and national figures, they are less likely to provide targeted, localized representation to their constituents.

These electoral patterns directly shape how members approach representation itself. The particular mix of incentives created by district lines, electoral rules, and voting patterns influences which constituencies representatives prioritize and how they balance competing representational demands.

Representation: Theoretical Models and Practical Realities

What Does It Mean to Represent?

Electoral systems determine who serves in Congress, but they don't dictate how these elected officials should represent their constituents. This raises a fundamental question: what does it mean to "represent" someone in a democratic system?

Political scientist Hanna Pitkin (1967) identified four distinct forms of representation that help us understand this complex relationship:

Formalistic Representation This type concerns the institutional arrangements that establish representative relationships. It has two components:

Authorization: The process (typically elections) by which representatives gain legitimate authority to act for constituents.

Accountability: Mechanisms (like regular elections) that allow constituents to evaluate and potentially remove representatives.

These institutional arrangements ensure that representatives maintain some responsiveness to constituent interests, even if specific votes don't always align with majority preferences in their districts.

Descriptive Representation Descriptive representation concerns whether representatives share demographic characteristics and life experiences with their constituents. By this measure, Congress has become increasingly diverse but still falls short of proportional representation:

Gender: Women constitute approximately 25-30% of Congress despite making up 51% of the population.

Race and ethnicity: Racial minorities have increased their representation but remain underrepresented relative to their share of the population.

Descriptive representation matters because shared characteristics and experiences can influence policy priorities and perspectives. Research suggests that having more women and racial minorities in Congress affects which issues receive attention and how they are addressed.

However, descriptive representation extends beyond demographic characteristics to include other relevant experiences. Representatives from agricultural districts often have farming backgrounds; those from military-heavy districts frequently have military experience. These shared experiences can help representatives understand constituent needs based on firsthand knowledge.

The gradual increase in congressional diversity reflects changing social attitudes and the removal of formal and informal barriers to political participation. However, the persistent gaps demonstrate that achieving fully descriptive representation remains an ongoing challenge in American democracy.

Symbolic Representation Representatives often engage in symbolic actions that express constituents' values and identities without necessarily creating policy changes. Examples include:

The "Tennessee Three" incident, where Democratic state legislators led protests over gun laws on the chamber floor.

Representatives wearing symbolic clothing or pins to signal alignment with constituent values.

Making speeches or statements that affirm shared values with constituents, even if they do not substantively change policy.

These symbolic acts serve an important expressive function, showing constituents that their representative "stands for" their community and values. These may ultimately lead to substantive changes in policy, but they need not to provide value to constituents.

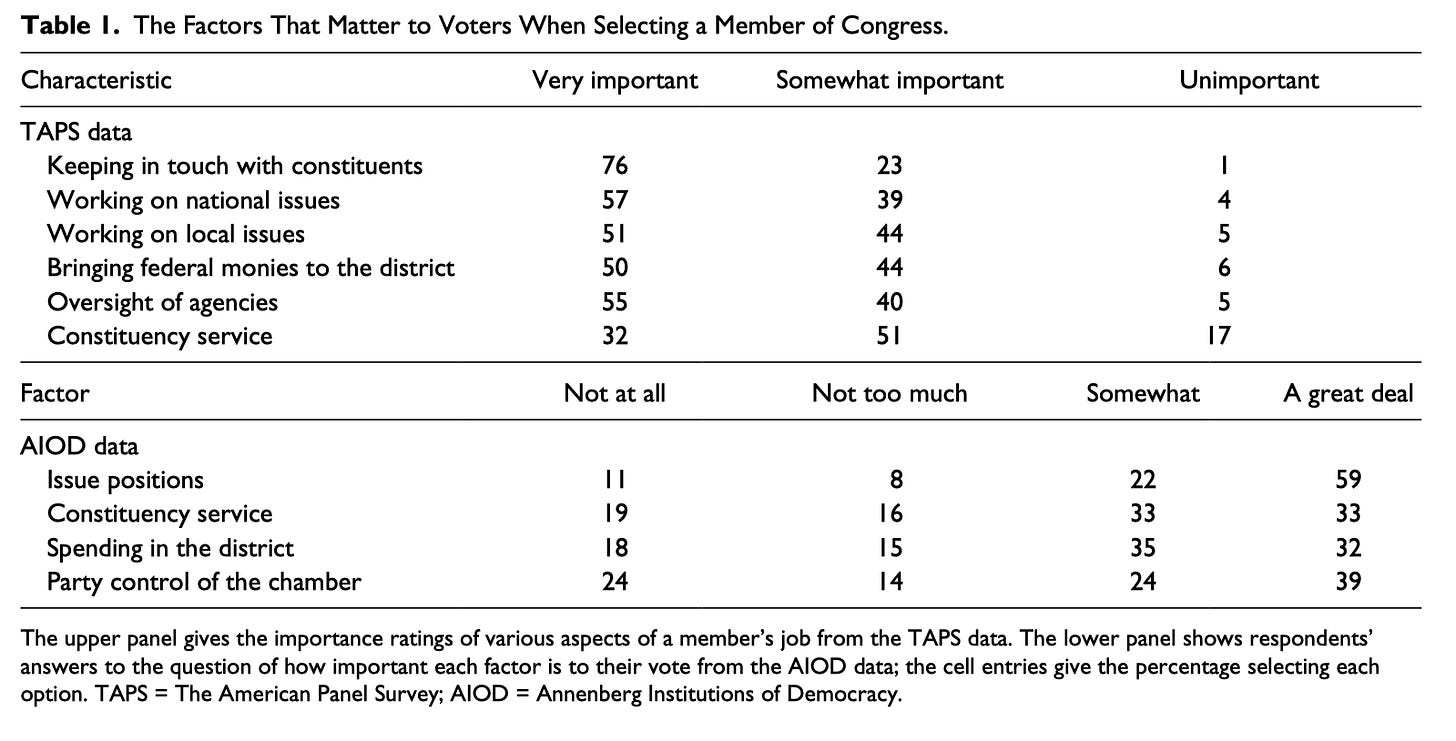

Substantive Representation This form involves representatives advancing the policy interests and preferences of their constituents through legislative action. Research by Lapinski and colleagues (2016) suggests that constituents generally prioritize this type of representation, valuing representatives who keep in touch with constituents and represent them effectively on specific issues, more than constituency service or securing local projects.

Delegates vs. Trustees: Models of Representation

When making policy decisions, representatives must determine how closely to follow constituent preferences. Two classic models capture different approaches:

Delegate model: Representatives follow the expressed preferences of constituents, prioritizing public opinion over personal judgment.

Trustee model: Representatives follow their own understanding of what's best for constituents, using personal judgment and expertise.

In practice, most representatives operate somewhere between these models. Ultimately, we may want our representatives to follow the will of the people on some issues, but not others. We might also change our opinion on the kind of representation we want when the lawmaker is from our party versus the other.

The Spatial Model: Ideology and Strategic Voting

Another way to understand legislative decision-making is through the spatial voting model, which imagines both legislators and policies along an ideological spectrum from liberal (farthest left) to conservative (farthest right). For example, you might imagine a liberal policy like "Medicare for All" on the far left and a policy like a fully privatized healthcare market (with no government involvement) on the far right. All other positions in between represent ideological compromises. This model assumes that legislators have fixed ideological "ideal points" and prefer policies closer to these points.

Within this framework, legislative outcomes depend on the distribution of members' ideal points (their preferred policies) and the position of the status quo. A policy change occurs only when a majority of legislators prefer the new policy to the current situation. In this model, legislators prefer policies that are closer in distance to their ideal point. As Lewis and King (1999) illustrate, if we place legislators along an ideological spectrum—with members like Senator Kennedy on the left and Senator Helms on the right—we can predict voting patterns based on how proposed policies would move relative to the status quo.

For example, suppose the status quo (current policy) is positioned in the center-left of the spectrum (the point labeled “You”). A moderate Republican like Senator Snowe would be able to move the bill rightward to her ideal point, as both more moderate (Kassebaum) and more conservative (Helms) Republicans would vote for it (it reduces the distance between themselves and the bill) while liberal Democrats (Kennedy) and moderate Democrats (Nunn) would vote against it (it increases the distance). However, a conservative like Helms would not be able to move the bill to his ideal point because it would increase the distance for all other members, including fellow Republicans. Even though Snowe and Kassebaum are also Republicans, the spatial model predicts they will vote against moving the bill to Helms's ideal point because it makes them worse off.

The spatial model reveals how factors beyond simple party identification shape legislative behavior. Two legislators from the same party but with different ideological positions may vote differently on the same bill if it falls between their ideal points. Similarly, the model helps explain why shifting the status quo even slightly can sometimes require complex negotiations and strategic positioning. Understanding where members' ideal points lie—and how they relate to the status quo—often provides more analytical power than simply knowing party affiliation.

This model also helps explain gridlock. When the status quo falls within what political scientists call the "gridlock interval"—the range between the pivotal votes needed to pass legislation—no change can secure majority support. This creates policy stability but can also prevent adjustments to changing circumstances when members' ideal points are highly polarized.

The spatial voting model, along with the delegate and trustee frameworks, highlights the multifaceted nature of the representative relationship. Representatives must balance constituent preferences, personal judgment, party expectations, and ideological commitments as they navigate their roles. The ways they resolve these tensions directly shape how Congress functions as a collective body.

Congressional Organization: Solving Collective Action Problems

Congress faces enormous challenges in functioning effectively as a legislative body. With 535 members representing diverse constituencies and ideological perspectives, how does it overcome the coordination and collective action problems inherent in such a large group? Just as citizens delegate authority to government to solve societal collective action problems, members of Congress have developed institutional mechanisms to facilitate decision-making and coordinate action.

The Committee System: Specialization and Expertise

One of Congress's primary organizational innovations is its committee system. The committee structure addresses several crucial challenges:

Information and Expertise Members of Congress must make decisions on countless complex issues—from healthcare reform to defense procurement, environmental regulation to international trade—with limited time and expertise. The committee system addresses this through specialized division of labor:

Standing committees: Permanent committees with fixed jurisdictions (e.g., Agriculture, Armed Services, Judiciary) where members develop specialized expertise.

Subcommittees: Further specialization within standing committees on specific issues.

Select and special committees: Temporary committees formed to address specific issues or investigations.

Joint committees: Committees with members from both chambers.

Conference committees: Temporary committees formed to reconcile differences between House and Senate versions of legislation.

Members serving on committees hold hearings to gather information from various sources. Research by Ban, Park, and You (2023) shows that different types of witnesses provide different kinds of information: executive branch officials and think tanks typically offer more analytical information, while interest groups and citizen witnesses often provide personal experiences and perspective.

Strategic Committee Assignments Committee assignments are not distributed randomly. Members seek assignments that align with their interests, constituent needs, and career ambitions:

Representatives from agricultural districts prioritize seats on the Agriculture Committee.

Those interested in foreign policy seek Foreign Affairs/Relations assignments.

The most powerful committees—often called "money committees"—handle appropriations, taxation, and financial regulation. Many members want to sit on these committees, which give them influence over how money is prioritized and spent.

In the House, party leaders control committee assignments, giving them leverage over members who might otherwise "buck the party." In the Senate, committee leadership positions are generally assigned by seniority, creating different incentive structures in each chamber.

The committee system creates policy experts but also raises concerns about representativeness. Members with specialized knowledge about an issue have the most influence over policy, but it also limits the degree to which non-specialists members have a chance or the confidence to advocate on behalf of their own constituents.

Party Organizations: Coordination and Agenda Control

Political parties provide another mechanism for solving Congress's collective action problems. By organizing members into coherent groups, parties can:

Coordinate legislative strategies across diverse issues.

Develop common policy priorities.

Assign specialized roles (whips, committee leaders, negotiators).

Provide voting cues for members without issue-specific expertise.

Party leaders in both chambers wield significant agenda-setting powers, determining which bills receive floor consideration and under what procedural rules. In the House, the majority party's control is particularly strong through the Rules Committee, which sets the terms of debate and amendment. In the Senate, the Majority Leader's scheduling power and unanimous consent agreements serve similar functions, though with more opportunities for minority influence.

Party discipline has strengthened in recent decades as ideological sorting has aligned party membership more closely with ideological positions. This increased cohesion facilitates coordination but also contributes to partisan polarization when the parties hold divergent policy positions.

Rules and Procedures: Structuring Deliberation

Both chambers have developed elaborate rules and procedures that structure the legislative process. These include:

Rules governing debate time and amendment opportunities.

Recognition practices determining who can speak and when.

Voting procedures that shape decision outcomes.

Scheduling mechanisms that determine which issues receive consideration.

These procedural rules are not merely technical details; they have profound consequences for policy outcomes. For example, whether a bill can be freely amended on the floor or comes under a "closed rule" barring amendments significantly affects both its content and likelihood of passage.

In the Senate, the filibuster—the ability to extend debate indefinitely unless 60 senators vote for cloture—has evolved from a rarely used tactic to a de facto supermajority requirement for most significant legislation. This procedural tool gives the minority party substantial blocking power, affecting both what passes and how legislation is crafted to attract the necessary supermajority support.

The organizational structures of Congress reflect members' practical responses to the challenges of legislating in a large, diverse body. By delegating authority to committees, party leaders, and established procedures, members trade some individual influence for greater collective efficiency. These institutional arrangements directly shape the legislative process we'll examine next.

Regular Order: The Textbook Process

The traditional legislative process—often called "regular order"—follows a series of defined steps designed to ensure thorough consideration of legislation while providing multiple opportunities for input and amendment. Understanding this process helps clarify how structural features like committees and parties influence lawmaking.

The basic steps of regular order include:

Bill introduction: A member introduces legislation in either chamber.

Committee referral: The bill is assigned to the relevant committee(s) based on its subject matter, but the committee need not take up the bill (this is where most bills die).

Committee consideration: The committee holds hearings, debates, and "marks up" (amends) the legislation.

Floor consideration: If approved by committee, the bill moves to the full chamber for debate and amendments.

Passage: The chamber votes on the final version.

Consideration in the other chamber: The process repeats in the second chamber, as the same bill must pass both chambers.

Conference committee: If the chambers pass different versions (because the second chamber made changes), a conference committee (including members of both chambers) reconciles differences.

Final passage: Both chambers vote on the reconciled version.

Presidential action: The president signs or vetoes the legislation.

Veto override. If the president vetoes the bill, a two-thirds majority of both chambers is needed to override the veto and pass the legislation into law.

This process includes multiple "veto points" where legislation can be blocked: committee chairs can refuse hearings, rules committees can block floor consideration, filibusters can prevent Senate votes, and the president can ultimately veto passed legislation.

The multiple veto points reflect the constitutional framers' preference for deliberation and consensus over efficiency, creating a system where legislation requires broad support rather than simple majorities to become law. This design helps protect against hasty or ill-considered legislation but can also impede timely responses to pressing problems.

Further reading:

Unorthodox Lawmaking: Contemporary Realities

Despite its prominence in textbook descriptions, regular order has become increasingly rare in modern Congress. As political scientist Barbara Sinclair documented, "unorthodox lawmaking" has become the norm, characterized by:

Bypassing committee consideration or holding abbreviated hearings.

Developing major legislation through leadership negotiations rather than committee markup.

Using procedural maneuvers to limit amendments and debate.

Bundling multiple policy areas into omnibus legislation.

Relying on reconciliation procedures to avoid filibusters on budget-related matters.

As one member, Representative Scott Peters (D-CA), colorfully described it, "Regular order is the Congressional Bigfoot...We're all told it exists, and none of us has ever seen it." This departure from traditional processes reflects both increasing partisan polarization and the growing competitiveness of elections, which incentivize stronger party discipline and strategic procedural maneuvering.

Under unorthodox lawmaking, party leaders typically negotiate major legislation behind closed doors, presenting completed bills to rank-and-file2 members with limited opportunities for amendment or input. While members may complain about being excluded from the process, they often accept these arrangements because:

They generally trust their party leadership to represent their interests.

The alternative might be no legislation at all on important issues.

The majority party benefits from limiting minority party opportunities for obstruction.

Rank-and-file lawmakers can always demand their leaders change tactics and return to regular order. They complain often, but do not typically force their leaders to change strategies because the benefits outweigh the costs.

Case Study: The Budget Process

The annual federal budget process illustrates both the formal structure and informal realities of congressional lawmaking. In theory, the process follows a predictable sequence:

The president submits a budget proposal (February).

Congress adopts a budget resolution setting overall spending targets (April).

Appropriations committees develop 12 separate funding bills for different government functions.

Both chambers pass these bills and reconcile differences.

The president signs the appropriations before the fiscal year begins (October 1).

In practice, this orderly process rarely occurs. Instead, Congress frequently relies on:

Continuing resolutions (CRs): Temporary funding measures that maintain existing spending levels when appropriations bills aren't completed on time.

Omnibus appropriations: Consolidated bills combining multiple appropriations into one massive package.

Last-minute negotiations: Deals struck near deadlines to avert government shutdowns.

These departures from the formal process reflect the political challenges of building majority coalitions around spending priorities, especially in a polarized environment where the parties hold fundamentally different views about the appropriate size and role of government.

Recent budget battles illustrate how competing goals shape congressional behavior. When members withhold support for spending bills or threaten government shutdowns, they may be:

Signaling fiscal conservatism to voters (re-election goal).

Attempting to reduce government spending (policy goal).

Seeking concessions for their vote (influence goal).

Protecting their party's reputation by holding out for their demands (collective partisan goal).

The evolution from regular order to unorthodox lawmaking demonstrates how Congress adapts its processes in response to changing political conditions, even as its formal rules remain largely unchanged. These adaptations directly affect both the substance of legislation and public perceptions of Congress.

Congress and the Public: Approval, Accountability, and Responsiveness

Public Opinion of Congress

Congress often receives low approval ratings, with recent polls showing only about 29% of Americans approving of the job Congress is doing. This unpopularity stems from several factors:

The public visibility of conflict and partisan bickering.

The tendency for people to want bipartisanship, but primarily when the other side is the one compromising.

The disappointment when compromise leads to partial rather than complete policy victories.

Despite these low institutional approval ratings, many individual representatives maintain higher popularity in their own districts. This "I like my representative but hate Congress" phenomenon reflects both the effectiveness of individual constituency service and the success of representatives in distancing themselves from the institution's perceived failings.

Conclusion: The Enduring Challenges of Congressional Democracy

The United States Congress embodies both the promises and challenges of democratic governance. Its structure creates a representative body capable of translating diverse public preferences into coherent policy, while its complex procedures ensure deliberation and protect minority interests. At the same time, these same features can produce frustration when they impede action on pressing problems.

Throughout this chapter, we've examined how members of Congress pursue multiple goals simultaneously—re-election, good public policy (as they define it), and influence within the institution. The pursuit of these goals shapes how they approach representation, whether emphasizing symbolic actions that resonate with constituents, providing substantive policy representation on key issues, or building descriptive connections with those they represent.

The constitutional framework establishes a bicameral legislature with distinct chambers that differ in size, term length, and representational basis. This design reflects the framers' desire to create an institution that would be both responsive to public sentiment and capable of deliberative decision-making. Electoral systems determine who serves in Congress and create incentives that shape their behavior once in office.

Congress's complex relationship with the public illustrates the inherent tensions in representative democracy. While the institution often receives low approval ratings, individual members typically maintain stronger support in their districts. This paradox reflects both the localized nature of representation and the challenges of collective action in a large, diverse legislative body.

The legislative process reflects both the formal rules established in the Constitution and the informal adaptations that have evolved to manage the challenges of lawmaking in a complex democracy. While "regular order" provides a structured path for legislation, contemporary Congress increasingly relies on "unorthodox lawmaking" to overcome gridlock and navigate partisan polarization.

Understanding these institutional structures and individual incentives helps explain both the achievements and limitations of Congress. When we observe budget standoffs, leadership contests, or partisan debates, we can recognize these not as random events but as rational responses to the complex environment in which members operate. By identifying lawmakers’ goals, we gain insight into how Congress functions within our democratic system.

Key Terms

Rational choice theory: A framework assuming that political actors make calculated decisions to maximize specific objectives within institutional constraints.

Fenno's goals: Richard Fenno's identification of three primary objectives for members of Congress: re-election, good public policy, and influence within Congress.

Gerrymandering: Drawing district boundaries to advantage particular parties or groups.

Single-member districts: Electoral systems where each geographic district elects just one representative.

Plurality voting: Electoral system where the candidate with the most votes wins, even without a majority ("first-past-the-post").

Descriptive representation: When representatives share demographic or experiential characteristics with their constituents.

Substantive representation: When representatives advance the policy interests and preferences of their constituents.

Symbolic representation: When representatives express constituents' values through symbolic actions or statements.

Delegate model: A theory of representation where representatives follow constituents' expressed preferences.

Trustee model: A theory of representation where representatives use their own judgment about constituents' best interests.

Spatial voting model: A theory that positions legislators and policies along an ideological spectrum to predict voting behavior.

Regular order: The traditional step-by-step legislative process from bill introduction through committee consideration to floor vote.

Unorthodox lawmaking: Modern legislative practices that bypass traditional procedures, often concentrating power in party leadership.

Filibuster: A Senate procedure allowing extended debate that can block legislation without 60 votes for cloture.

Constituent refers to someone the member of Congress represents.

Rank-and-file refers to regular (non-leader) members of Congress.