Local Politics, National Problems

The challenges of federalism and the decline of local politics in an era of partisan polarization.

Learning Objectives

Understand the concept of federalism and its historical development in the American political system.

Analyze the evolution of federal-state relationships.

Identify the factors driving the nationalization of American politics.

Evaluate how nationalization affects representation, electoral outcomes, and policy decisions.

Explain the implications of partisan trifectas at the state level for policy and governance.

Introduction: The Tension Between National and Local Governance

Should policy be set at the national level? Or should states lead on policy?

This seemingly straightforward question reveals a fundamental tension that has shaped American politics since the founding era. The United States operates within a federal system that divides power between national and state governments—a structure that makes American governance distinctive among modern democracies. Yet over time, this relationship has evolved dramatically, with an increasing shift toward national politics and policy.

This nationalization of American politics—the growing tendency for voters, candidates, and issues to focus on national rather than local concerns—represents one of the most significant transformations in contemporary governance. As political scientist Morris Fiorina observes, "People vote for the party, not the person." This pattern would have surprised the Constitution's framers, who designed a system where local representation was intended to serve as a counterweight to national power. As we will see, the federal structure designed to protect local interests and limit centralized power now operates in ways its creators could hardly have imagined.

Federalism: Constitutional Design and Evolution

The Constitutional Framework

At its core, federalism is a way of organizing government that divides power between a central (federal) government and regional (state) governments. Some tasks, like national defense or printing money, are handled by the federal government. Other responsibilities, like issuing driver's licenses or regulating abortion laws, are primarily managed by state governments.

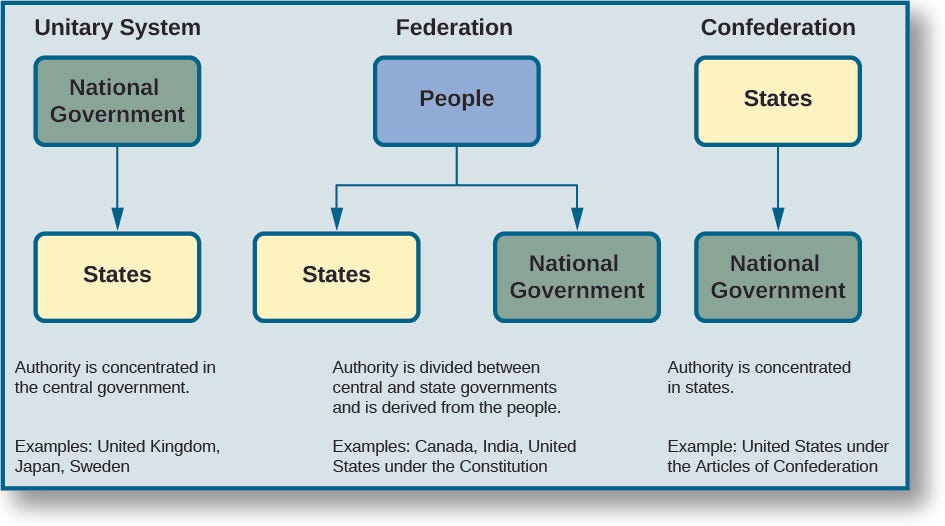

The way in which the United States divides national and local powers is distinct. Many countries use a unitary system where the national government holds most of the power and local governments simply carry out the national government's decisions. Places like the UK and Japan follow this model. Other countries have used a confederation model, where most power stays with individual states or regions, and the central government is relatively weak. The United States tried this approach under the Articles of Confederation. The European Union is another example of a confederation. It’s a collective body where most of the power resides with individual member countries.

The American system sits between these two extremes. The Constitution creates a hybrid approach where both levels of government have their own independent sources of power and authority. Neither level is completely dependent on the other. Both have specific areas where they can act on their own, which is explicitly provided for in the Constitution.

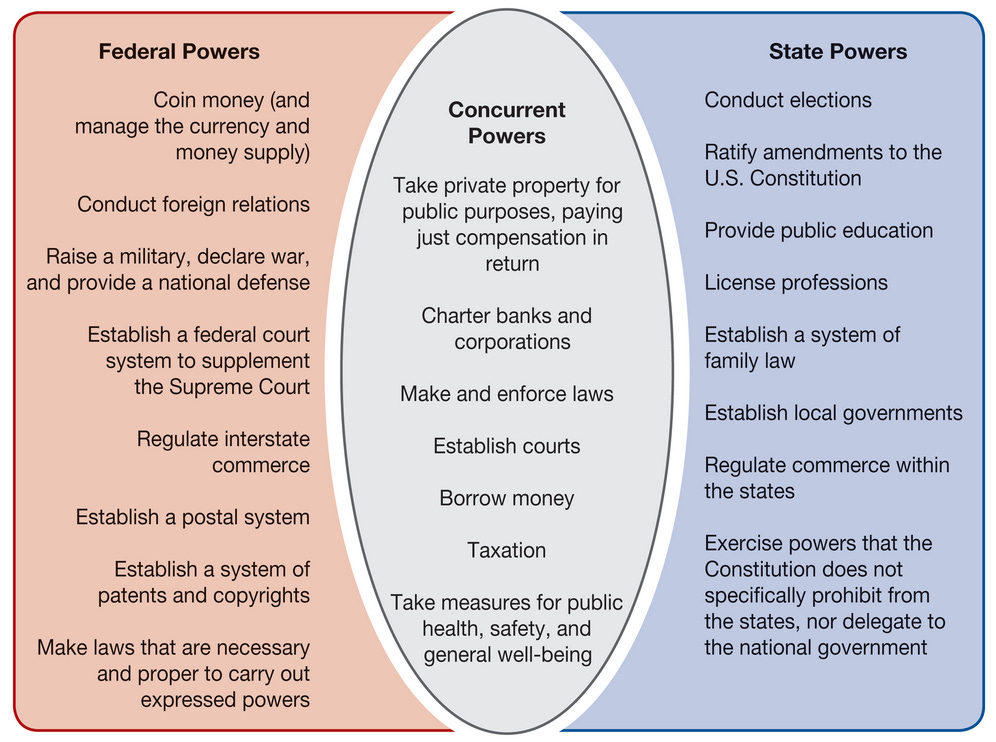

The Constitution established specific enumerated powers for the federal legislature in Article I, Section 8, including authority to regulate interstate commerce, establish a national currency, declare war, and collect taxes. The Tenth Amendment clarified that "powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." This amendment reflected the framers' intent to create a limited national government, with states retaining significant authority.

Notably, the Constitution makes no mention of local governments—counties, cities, and municipalities exist at the pleasure of state governments rather than having constitutionally protected status. States can alter local government boundaries, powers, and even existence, making local governments fundamentally dependent entities within the federal structure.

Why Federalism?

The adoption of federalism reflected both practical and philosophical considerations. Historically, the independent colonies had developed their own governance structures and identities, with citizens often identifying more strongly as Virginians or New Yorkers than as “Americans.” When it came to the devising the Constitution, state politicians naturally resisted surrendering power to a new national government. The Great Compromise, then, balanced power between the federal and state governments. This structure, once established, created its own institutional momentum that continues to influence contemporary politics (i.e., path dependence).

Beyond historical circumstances, federalism also addressed concerns about governmental power. The Anti-Federalists, who opposed the Constitution's ratification, worried particularly about an overly powerful central government and advocated for explicit protections for individual liberties and state authority. Their advocacy led to the ratification of the Bill of Rights, including the 10th Amendment, which reserved non-enumerated powers to the states.

A later justification for federalism emerged in the concept of "laboratories of democracy." As Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously wrote in 1932, "A single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country." This argument suggests that federalism enables policy innovation and experimentation. A state can experiment with a policy and see the results. If the policy is successful, it can spread to other states. If it fails, that failure will be contained to a single state and others will know not to adopt it.

Dual and Shared Federalism

American federalism has operated in two primary way: dual federalism and shared federalism.

Dual federalism recognizes separate spheres of authority, with each level of government having exclusive jurisdiction in certain areas. For example, the federal government handles national defense and foreign policy. States conduct elections, create and handle criminal law, and deal with other domestic concerns.

Shared federalism (sometimes called "cooperative federalism") recognizes concurrent powers where both levels exercise authority in the same domains. Taxation, business regulation, and environmental protection exemplify areas where federal and state governments maintain overlapping responsibilities. This approach acknowledges that many contemporary problems cross state boundaries and require coordinated responses.

The balance between these models has shifted significantly over time. The early republic operated primarily under dual federalism, with limited federal involvement in domestic policy. However, the 20th century witnessed a dramatic expansion of shared federalism as both economic and social challenges demanded national responses.

The Trend Toward National Power

Over American history, the federal government has gradually assumed greater responsibility and authority relative to the states. Several factors have driven this shift toward nationalization of governance.

First, growing federal responsibility reflects expanded public expectations for government services. Programs addressing economic security, health care, civil rights, and environmental protection have typically required national coordination. As government's role in public life increased—particularly after the New Deal and Great Society eras—federal authority expanded correspondingly.

Second, constitutional interpretation has facilitated this expansion through two key provisions. The Supremacy Clause establishes that federal law takes precedence over state law when conflicts arise. While initially intended for limited application, this principle has gained importance as federal legislation has expanded into domains previously managed by states. Similarly, the "Necessary and Proper" Clause (sometimes called the Elastic Clause) authorizes Congress to make laws needed to execute its enumerated powers. This provision has enabled federal expansion into areas not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution but connected to established federal responsibilities.

Third, structural changes have altered federalism's operation. The Seventeenth Amendment established direct election of senators in 1913, replacing selection by state legislatures. This reform weakened senators' institutional connection to state governments and reduced their incentive to protect state prerogatives against federal encroachment.

These factors have collectively produced a federal government far more powerful and pervasive than the framers envisioned. While states retain important authorities—particularly in areas like education, criminal justice, and family law—the overall trajectory has moved steadily toward greater national authority.

Nationalization of American Politics

Beyond formal governmental structures, a profound transformation has occurred in how Americans experience and participate in politics. Political nationalization refers to the increasing tendency for local and state politics to reflect national partisan divisions rather than distinctive local concerns.

Dimensions of Nationalization

Nationalization manifests in several ways:

Knowledge and attention patterns: Citizens typically possess greater knowledge about national politics than state or local affairs. Most Americans can identify the president and major national issues but struggle to name their state legislators or understand local policy debates.

Evaluation criteria: Voters increasingly apply the same partisan criteria to candidates at all levels, from president to local officials. Rather than judging candidates based on their specific qualifications or positions on local issues, many voters simply support their preferred party across the ballot.

Presidential influence: Presidential politics increasingly determines outcomes in congressional, state, and even local elections. Districts that support a particular party's presidential candidate typically elect that same party's candidates to Congress, state legislatures, and other offices.

Party-based voting: Party identification has become the dominant factor in voting decisions, overwhelming candidate-specific factors like experience, ideology, or constituency service.

These patterns represent a significant departure from earlier eras when politics maintained a more local character. Throughout much of American history, candidates cultivated personal reputations distinct from their party affiliation, and voters often split their tickets between parties depending on the specific office and candidate. Today, straight-ticket voting has become the norm rather than the exception.

Electoral Consequences of Nationalization

Nationalization has produced several notable electoral patterns.

Split-ticket voting has declined. In the 1970s, nearly half of congressional districts elected representatives from a different party than their presidential preference. Today, such split districts have nearly disappeared.

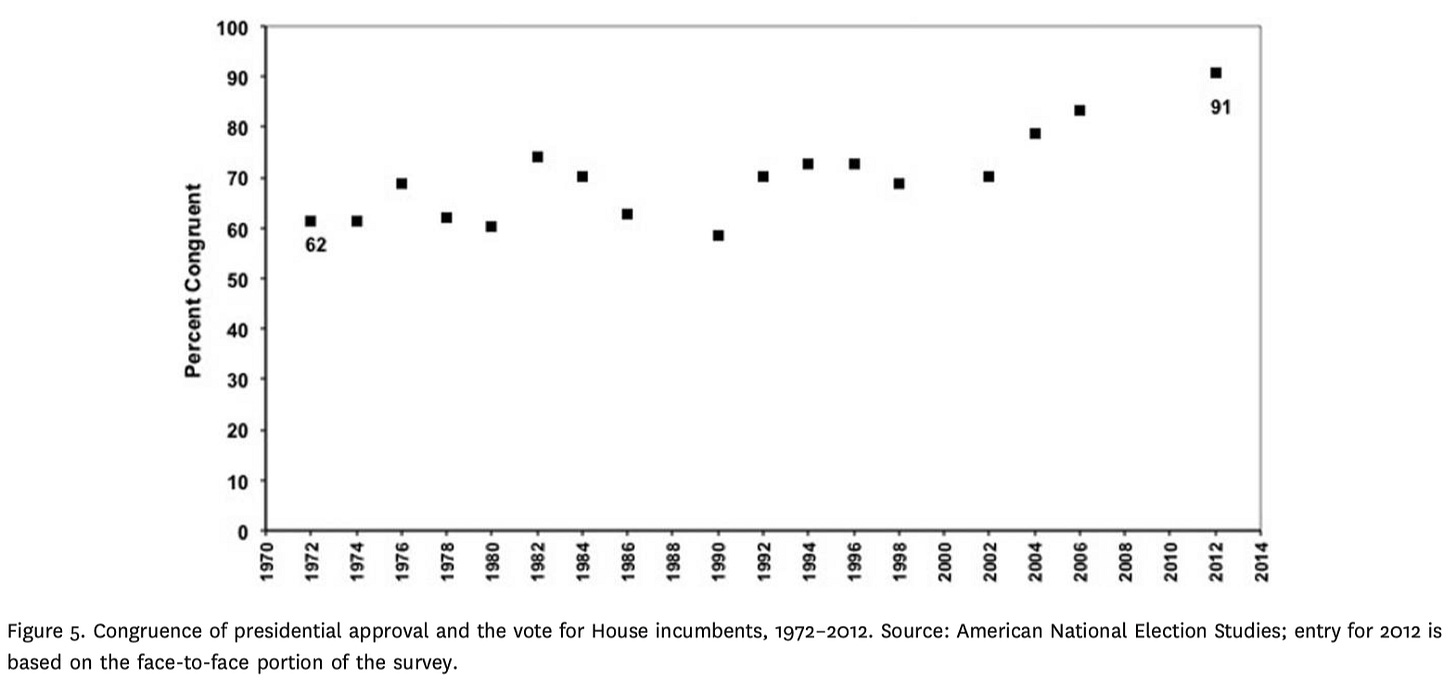

Presidential approval has become increasingly predictive of congressional voting. In 1970, the percentage of people who approved of the president voting for that party's House candidate was about 62%. In 2014, that number had increased to 91%. This trend means that congressional elections increasingly function as referendums on the president rather than assessments of individual representatives.

The president's vote share in a district has become more predictive of congressional outcomes than a candidate's own previous performance. This pattern, which emerged in the mid-2000s, reveals the dominance of national political forces over candidate-specific factors. Even though a candidate's previous vote often represents the same individual running for reelection, with established constituency relationships and local recognition, the national partisan environment—as reflected in presidential voting patterns—now carries greater electoral weight. This shift demonstrates how representatives' electoral fortunes increasingly depend on their party's national standing rather than their individual record of local service or responsiveness.

State Government Trifectas

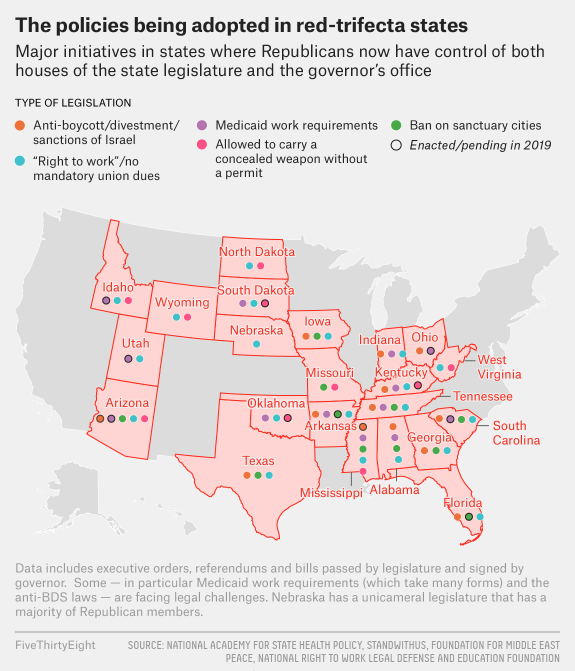

Nationalization has transformed state politics as well, with increasing partisan alignment between state and national governance. One prominent manifestation is the rise of "trifectas"—arrangements where one party controls the governorship and the state legislature.

Just like when government is unified, with the presidency and Congress being controlled by the same party, we are seeing state government trifectas use unified government to enact partisan agendas. The number of state trifectas has increased while divided state governments have decreased. This trend reflects greater partisan sorting at the state level, with fewer states maintaining distinctive political cultures separate from national partisan identity.

State trifectas typically pursue policy agendas aligned with national partisan priorities rather than developing unique state-specific approaches. In 2019, Perry Bacon Jr. found that Democratic trifecta states pursued policies like higher minimum wages, free college programs, and marijuana legalization, while Republican states advanced right-to-work laws, Medicaid work requirements, and less restrictive gun regulations.

These partisan differences exemplify how nationalization has reduced policy variation across states despite their continued formal authority. Rather than fifty distinctive approaches reflecting local conditions and preferences, state policies increasingly cluster into two partisan models aligned with national political divisions.

Causes of Political Nationalization

Multiple factors have contributed to the nationalization of American politics, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that continues to reshape electoral behavior and governance.

Voter Sorting

The Republican Party is made up more and more of people who identify as conservative, and the Democratic Party is made up more and more of people who are liberal. This partisan sorting means voters with similar ideological beliefs increasingly cluster within the same party regardless of geographic location.

In earlier eras, both parties contained ideological diversity—conservative Southern Democrats coexisted with liberal Northern Democrats, while moderate Republicans served alongside conservatives. This diversity meant that candidates needed to appeal to distinctive local constituencies rather than relying on national partisan messaging.

Today, though, if most liberals are Democrats and most conservatives are Republican, then candidates do not necessarily need to appeal to their distinct local interests, because there really aren't any. Voters in San Francisco and New York increasingly share political preferences, as do voters in rural Texas and Wyoming, reducing the incentive for candidates to develop locally tailored positions.

Candidate Sorting

Candidates running for office often take their party’s line. There are very few Democratic candidates who take a pro-gun position, and there are very few Republicans who take a pro-choice position. This ideological sorting among candidates further reinforces nationalization by giving voters fewer opportunities to split their tickets based on issue preferences.

As Morris Fiorina notes, "we don’t know how many voters would split their tickets if they were offered chances to vote for conservative Democratic or liberal Republican House candidates because the parties offer them few such choices anymore." When candidates adopt nationally consistent partisan positions, voters naturally respond with nationally aligned voting patterns.

Campaign Finance

The nationalization of political funding has further diminished local distinctiveness in campaigns. Running for office is very expensive, and candidates increasingly rely on donations from across the country rather than just their local constituencies. When Democratic candidates in Texas receive substantial funding from donors in California, or Republican candidates in Minnesota attract donations from Florida, these candidates typically emphasize nationally resonant issues rather than state-specific concerns.

This nationalized funding pattern creates a feedback loop. The result is that candidates have strong incentives to position themselves according to national partisan expectations rather than distinctive local preferences to earn out-of-state contributions, further reinforcing the nationalization of political discourse and representation.

Media Nationalization

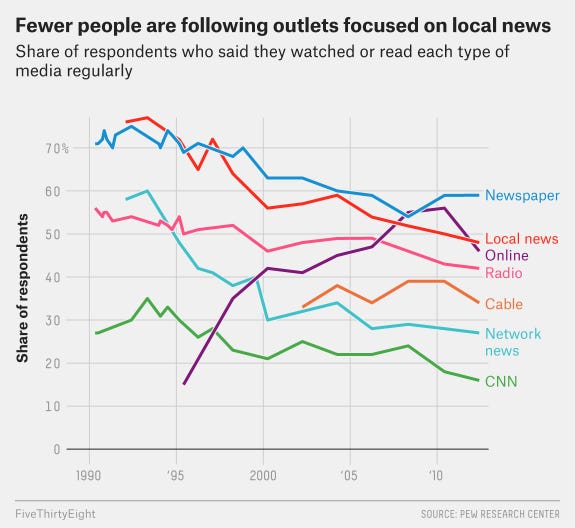

The American information environment has undergone a profound transformation that both reflects and reinforces political nationalization. This shift involves changes in both media supply and consumer demand that have collectively diminished the prominence of local news while elevating national political coverage.

On the supply side, the economics of media have increasingly favored national over local coverage. Since the 1980s, cable television networks like CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC have developed programming that appeals to nationwide audiences, allowing them to spread production costs across millions of viewers rather than just local markets. Similarly, digital news platforms optimize content for maximum audience reach, prioritizing stories with national significance over those with purely local interest. These national outlets focus on attention-grabbing headlines, partisan conflicts, and presidential politics that generate clicks and viewership across the country.

Meanwhile, traditional local news sources have experienced dramatic decline. More than half of the nation's counties—home to approximately 55 million Americans—now have no local news outlets at all. The number of local newspapers has fallen from about 9,000 in 2005 to roughly 6,000 today, with nearly 5,000 of those remaining papers publishing only weekly rather than daily. This reduction in local coverage creates information vacuums about state and local governance.

On the demand side, consumer preferences have shifted toward national content. Americans increasingly consume news through social media and national digital platforms rather than local sources. When given the choice between stories about dramatic national political conflicts and routine local governance issues, many consumers gravitate toward the former. This preference creates market incentives for media companies to further reduce investment in costly local reporting while expanding national political coverage.

The result is a self-reinforcing cycle of nationalization: As local news disappears, citizens have less information about state and local affairs while being continuously exposed to national partisan narratives. Without substantive knowledge about local governance, voters increasingly rely on national partisan cues when making electoral decisions about all levels of government. Politicians respond by emphasizing nationally resonant issues rather than local concerns, further diminishing the distinctiveness of local politics. When people lack access to robust local news, they cannot effectively monitor their state and local governments, weakening accountability and further nationalizing political attention.

Implications of Nationalization

The nationalization of American politics has produced both benefits and costs for democratic governance.

Benefits of Nationalization

We elect many officials in our federalist system. It is quite costly to learn about the specifics of all these candidates and make an informed choice. When parties are nationalized, the party label provides a cue to voters about who they should choose.

Party labels offer an informational shortcut that enables citizens to make reasonably informed choices despite limited knowledge about specific candidates. When parties maintain consistent ideological positions, voters can use party affiliation to identify candidates who broadly share their values and policy preferences.

Nationalization can also facilitate coordinated policy responses to problems that cross state boundaries. Climate change, economic inequality, racial justice, and other major challenges often require national approaches rather than patchwork state solutions. Strong national parties can develop comprehensive policy agendas addressing these issues rather than fragmented local approaches.

Costs of Nationalization

Despite these benefits, nationalization creates significant democratic challenges. One potential bad outcome of such a unity between presidential and congressional voting is that lawmakers feel more beholden to their parties. In the 1970s and 1980s, when members represented districts won by the other party's president, they couldn't just oppose everything the president wanted to do. After all, many of their constituents voted for the president.

This dynamic reduces incentives for bipartisan cooperation and compromise. When lawmakers represent districts that were won by their own party only, then they feel no need to accommodate the other party's president; or they may feel like they must support their party's president. The result is increasing congressional polarization that mirrors public partisan divisions.

Nationalization also weakens local representation by prioritizing partisan alignment over constituency responsiveness. If a representative’s own past vote share is less predictive than the president's vote share—which we could think about as representing more national forces—then lawmakers need to pay more attention to those national forces than their own district or constituents.

Finally, nationalization undermines federalism's potential for policy innovation through state experimentation. Rather than serving as "laboratories of democracy" testing various approaches, states increasingly adopt partisan policy templates developed nationally. This conformity reduces policy learning and adaptation to local conditions.

Conclusion: Federalism in a Nationalized Era

American federalism operates in a political environment dramatically different from the one in which it was designed. The Constitution created a system dividing power between national and state governments, with local representation serving as a foundational principle. Yet contemporary politics increasingly operates according to national partisan dynamics that transcend these constitutional boundaries.

This tension creates persistent challenges for democratic governance. When voters, candidates, and elected officials all prioritize national partisan considerations over local concerns, the federal system cannot function as the framers intended. Policy decisions increasingly reflect national partisan alignment rather than distinctive local needs or values.

Yet the formal structures of federalism persist, creating opportunities for resistance and adaptation. States continue to exercise significant authority in areas like education, criminal justice, and public health, sometimes innovating in ways that influence national policy debates. The formal division of power between national and state governments remains consequential despite the nationalization of partisan politics.

Understanding this complex relationship between federalism's constitutional design and its contemporary operation helps explain many features of modern American politics: partisan polarization, policy gridlock, and the increasing influence of presidential politics on all levels of government.

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of federalism today is not the specific division of powers established in the Constitution, but the opportunity for democratic experimentation and learning across different levels of government—an opportunity that persists despite, and sometimes because of, the nationalization of American politics.

Key Terms

Federalism: The constitutional division of power between national and state governments.

Dual federalism: A model where federal and state governments operate in separate spheres with distinct responsibilities.

Shared federalism: A model where federal and state governments exercise concurrent authority in many policy areas.

Supremacy Clause: Constitutional provision establishing that federal law takes precedence over state law.

Elastic Clause: Constitutional provision authorizing Congress to make laws "necessary and proper" for executing enumerated powers.

Nationalization: The increasing alignment of state and local politics with national partisan divisions.

State Government Trifecta: When one party controls the state legislature and the governorship.

Laboratories of democracy: The concept that states can experiment with different policies, allowing successful approaches to spread.