Learning Objectives

Understand the concept of polarization and how to measure it in American politics.

Analyze how polarization has evolved in Congress over time.

Identify the key factors that have contributed to increased polarization.

Evaluate how polarization affects presidential leadership and legislative rhetoric.

Explain how politicians strategically use polarization to their electoral advantage.

Introduction: The Divided States of America

"We've arrived at a crossroad, and we chose anger and division." These words from former Senator Kyrsten Sinema's 2023 retirement announcement capture a fundamental tension in contemporary American politics. Once elected as a Democrat in 2018, Sinema later became an independent, citing that "the only victories that matter these days are symbolic, attacking your opponent on cable news or social media." Her critique raises important questions about how American politics functions in an era of intense partisan division.

The politics of division that Sinema described aren’t simply a matter of heightened disagreement about policies. Rather, they reflect a fundamental transformation in how political competition operates in the United States. Politicians increasingly focus on attacking their opponents rather than passing legislation, voters respond more to negative messages about the opposing party than positive messages about their own, and the institutions designed to facilitate compromise struggle to function in this environment.

Defining and Measuring Polarization

What Is Polarization?

Polarization refers to a political environment characterized by small within-party differences and large between-party differences. In other words, members of the same party think and vote very similarly to each other, while the gap between the parties widens. This definition helps distinguish polarization from simple disagreement. Political conflict has always existed in American politics, but polarization describes a particular pattern of conflict where political actors increasingly sort into non-overlapping camps with little common ground between them.

This concept can be visualized through the distribution of political preferences as shown in the image below, which illustrates the difference between unpolarized and polarized political parties. To understand the figure, imagine we could place individuals on a scale from most liberal on the left to most conservative on the right (with people who are ideologically moderate in the middle). That’s the horizontal axis. On the vertical axis, as the curve goes up, more people place themselves at that point on the left-right scale.

In a fairly unpolarized system (left panel), preferences closely follow a unimodal distribution—a single-peaked curve where most individuals cluster toward the center, with few people at the extremes. Both parties contain members across the ideological spectrum with substantial overlap between parties. The curves are relatively wide, indicating diverse preferences within each party.

In a polarized system (right panel), preferences follow a bimodal distribution—two distinct peaks with a valley in the middle. Each party forms a separate cluster with little overlap. The curves are narrower, indicating greater similarity within each party, while the distance between the two curves represents the ideological gap between them. There are few people in the middle, and there is very little overlap between parties.

Measuring Congressional Polarization

Political scientists have expanded this idea and developed sophisticated methods to measure polarization in Congress using legislative voting behavior as an indicator. The most widely used approach is called NOMINATE, which place legislators on a left-right ideological spectrum based on their voting patterns, just like the image above.

The method works by analyzing how legislators vote relative to each other across many roll call votes in Congress. When two legislators frequently vote the same way, the model places them closer together on an ideological scale. When they rarely vote alike, they're placed far apart. This approach means researchers don’t have to subjectively determine which positions are "liberal" or "conservative." Instead, the patterns emerge from how lawmakers themselves vote.

To see how this works, imagine we had a five-member legislature voting on three issues: spending on defense, healthcare, and immigration.

In this simplified example, Alice and Destiny always vote identically and would be placed at the same point on the ideological spectrum. Jose votes opposite to them on every issue and would be placed at the opposite end. Maria and Keenan fall somewhere in between, with Maria closer to Alice/Destiny and Keenan closer to Jose based on their voting patterns. From this data, we now have a measure of where these five people sit on the ideological spectrum.

When applied to actual congressional voting data, this approach reveals striking patterns of polarization. In the image below, each point represents a member of the 118th (2023-2024) Senate. The farther left, the more liberal. The farther right, the more conservative. Like the image above, we can see that the two parties generally cluster together, and there is no overlap between members of opposing parties: the most conservative Democrat is to the left of the most liberal Republican.

In today's Congress, Democratic and Republican lawmakers cluster at opposite ends of the spectrum with virtually no overlap between the parties. However, this hasn't always been the case. Examining NOMINATE scores across time reveals a dramatic transformation in congressional polarization. In the mid-20th century, the parties showed considerable ideological overlap. Many conservative Democrats (particularly from the South) voted similarly to moderate Republicans, while liberal Republicans often aligned with moderate Democrats. For example, the NOMINATE scores of Senators in the 73rd (1933-1934) Congress are much closer together and feature some overlap between the parties.

By the 1990s, this pattern began to change significantly, and by the early 21st century, the parties had sorted into nearly non-overlapping camps. Today's Congress shows levels of polarization not seen since the late 19th century, with virtually no ideological overlap between the parties.

This polarization isn't limited to roll call votes. Studies of congressional speech patterns, campaign rhetoric, and legislative cooperation all show similar trends toward greater partisan division and less cross-party collaboration. The result is a political environment where party affiliation increasingly predicts not just how legislators will vote, but how they'll frame issues, which colleagues they'll work with, and even what words they’ll use.

Causes of Increased Polarization

The rise of polarization reflects complex changes in American society, electoral dynamics, and institutional practices. Political scientists have identified numerous contributing factors, which can be broadly categorized into electoral changes, institutional transformations, and strategic choices by political actors. Although a full discussion is beyond the scope of the article (but see Barber and McCarty 2015), a few key causes are summarized here:

Southern Realignment and Partisan Sorting

One of the most significant drivers of polarization was the partisan realignment of the American South. Throughout much of the 20th century, the Democratic Party used Jim Crow Laws to disenfranchise black voters and dominate elections in the South, winning nearly all congressional seats in the region. These Southern Democrats often held conservative positions on social issues while supporting more liberal economic policies—creating an ideologically diverse Democratic coalition.

Starting in the 1960s and accelerating in the 1990s, the Republican Party made significant inroads in the South. Democrats lost their dominant hold on Congress as they lost control of these seats. This transformation wasn't simply a geographic shift; it fundamentally altered the ideological composition of both parties. Conservative Southern Democrats were gradually replaced by conservative Southern Republicans. This made the Democratic Party more liberal (they lost their conservative members) and the Republican Party more conservative (they gained conservative members).

This regional realignment contributed to ideological sorting, where each party became more internally similar. Where the mid-century parties contained significant ideological diversity, the modern parties align much more closely with ideological positions. Today's Democratic Party is overwhelmingly liberal, while the Republican Party is overwhelmingly conservative.

This sorting extends beyond lawmakers to voters themselves. In the mid-20th century, many voters' partisan identities reflected regional or cultural traditions rather than ideological preferences. Today, voters' partisan affiliations more strongly align with their issue positions, creating more ideologically consistent electorates for each party.

Competitive Congressional Majorities

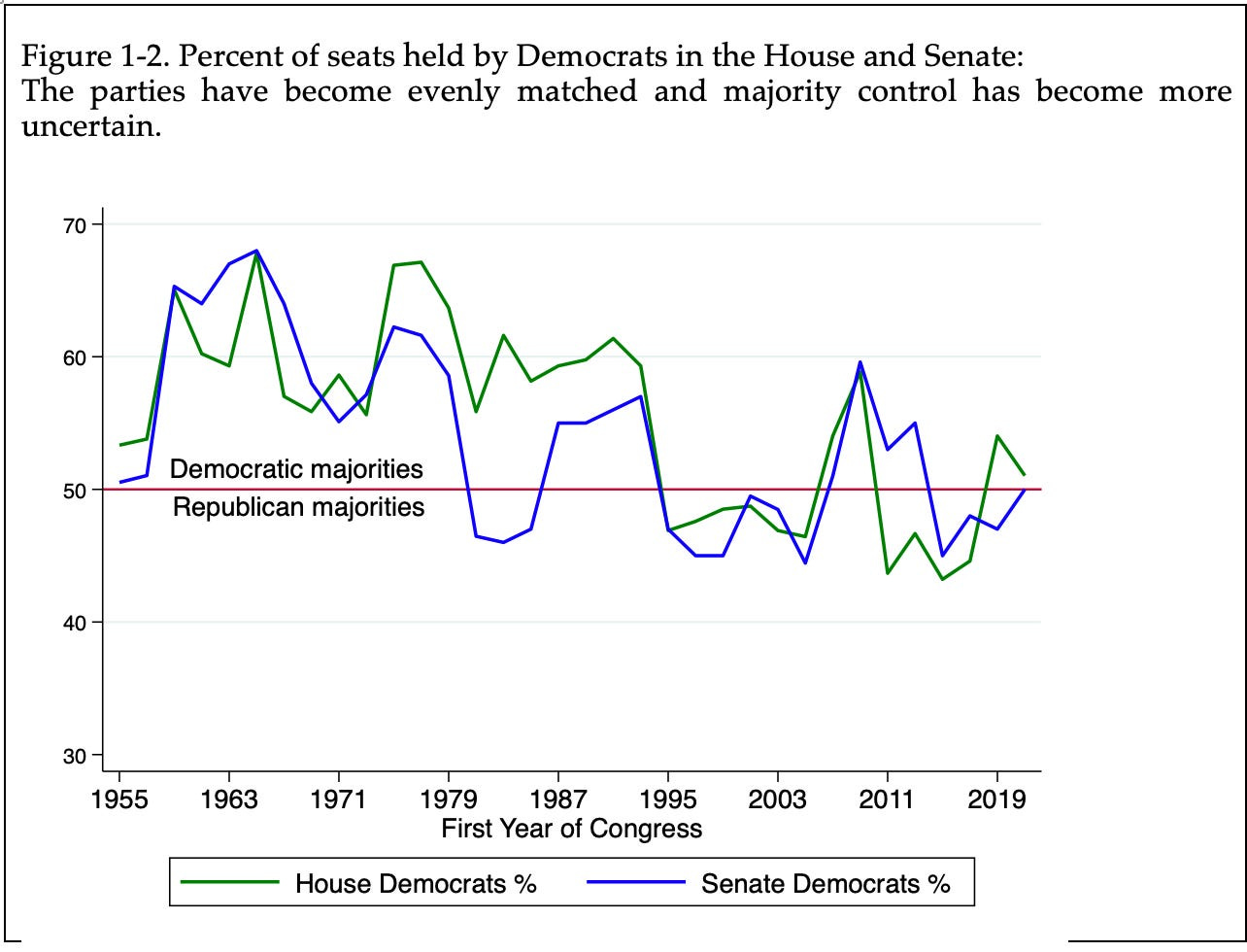

The structure of congressional competition has also changed dramatically. From the 1950s through the early 1990s, Democrats maintained uninterrupted control of the House of Representatives and held the Senate for most of that period. As political scientist Frances Lee describes, this stable Democratic majority created a political environment where:

Republicans had limited expectations of winning majority control.

The Republican minority’s best strategy was to work with the majority to influence legislation.

Democrats could afford internal disagreements without fear of losing majority status.

Beginning in the 1980s in the Senate and the 1994 "Republican Revolution" in the House, congressional control became much more competitive. Since then, narrow majorities and frequent power transfers have characterized Congress, with majority control hanging on the outcomes of a relatively small number of competitive districts.

This competitive environment creates what political scientist Frances Lee calls "insecure majorities," where both parties have realistic prospects of winning or losing control in upcoming elections. Under these conditions, the strategic calculus for both parties changes dramatically:

The minority party has incentives to obstruct rather than compromise, to deny the majority party legislative accomplishments.

The majority party focuses on party-line votes rather than bipartisan legislation to highlight differences with the opposition.

Both parties invest heavily in messaging and symbolic votes designed to appeal to their base and create negative perceptions of the opposition.

When majority control is consistently at stake, partisan competition intensifies and legislative productivity often suffers as a result. These fights are not always sincere policy disagreements. Rather, each party wants to make the other look ineffective and extreme so that they can keep or win the majority in Congress.

Decline of Split-Ticket Districts

Electoral changes have further reinforced polarization. In particular, the number of "split-ticket" congressional districts—those that vote for one party for president and another for Congress—has declined dramatically. In the 1970s, nearly half of all House districts showed split results between presidential and congressional races. Today, fewer than 10% of districts split their tickets.

This nationalization of congressional elections means that members increasingly rise or fall with their party's national brand and presidential candidates. Where once members of Congress could maintain independent identities and voting records, today's electoral environment rewards partisan loyalty and punishes deviation from party positions.

The decline in split-ticket voting reflects both voter sorting and the nationalization of American politics. As voters align their partisan and ideological identities more consistently, they become less likely to split their tickets. Meanwhile, national issues increasingly dominate local elections, with voters more focused on national party platforms than individual candidates' positions or personalities.

Negative Partisanship and Its Consequences

The rise of polarization has transformed how Americans relate to political parties, giving rise to what scholars call negative partisanship—where voters are motivated more by opposition to the other party than by positive attachment to their own.

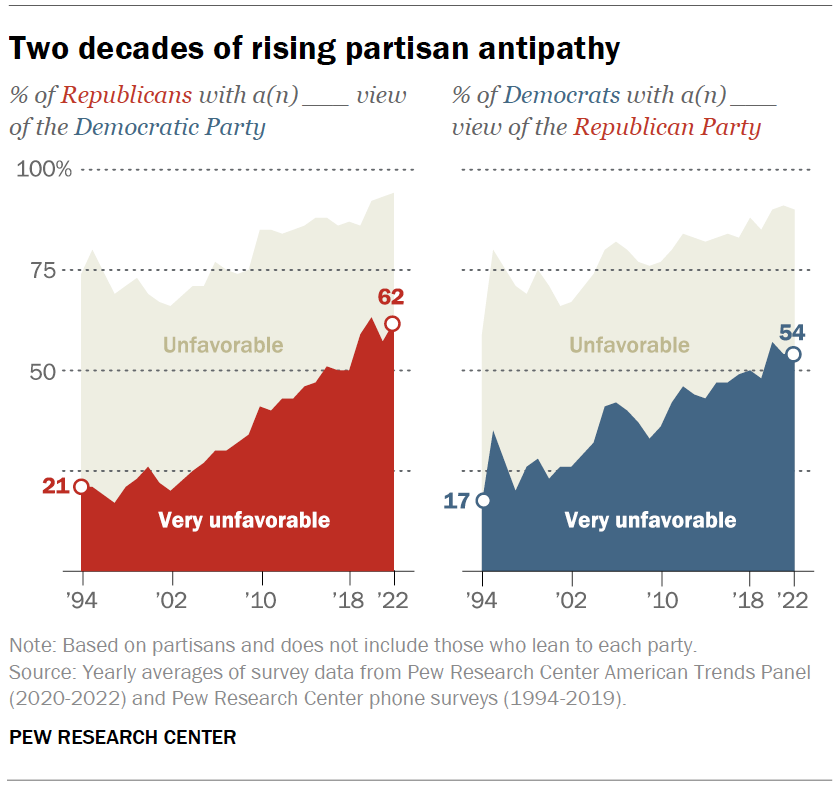

Survey data reveals a dramatic increase in negative feelings toward the opposing party. In the 1980s, only about 20% of Americans held strongly unfavorable views of the opposing party. Today, over half of partisans view the opposing party very unfavorably. Importantly, this increase in negative feelings hasn't been matched by increased positive feelings toward one's own party. Today, one’s negative feelings about the opposite party are a key driver of turnout in elections and can lead to democratic decline.

This negativity creates powerful electoral incentives for politicians. When voters are motivated primarily by opposing the other side, campaigns focus on highlighting the dangers of the opposition rather than the virtues of their own candidates or policies. Attack ads, dire warnings about the consequences of the other party's rule, and demonization of opposing leaders become standard campaign tactics.

How Politicians Weaponize Polarization

Politicians don't just respond to polarization—they actively weaponize it for electoral advantage. Understanding these strategic behaviors (which is core to Professor Noble’s own research) helps explain why polarization persists despite broad public dissatisfaction with partisan conflict.

Presidential References as Polarizing Signals

One strategy politicians use is selectively referencing the president to activate partisan reactions. Professor Noble’s research on congressional floor speeches reveals a consistent pattern: members of the opposition party mention the president far more frequently than members of the president's own party.

This selective presidential referencing isn't accidental—it's strategically designed to activate partisan responses. Polling consistently shows that attaching the president to policy decreases support, especially among those outside of the president’s party. This asymmetry creates powerful incentives for opposition politicians to focus their rhetoric on the president, knowing it will mobilize their base. The pattern appears consistently across administrations regardless of which party holds the White House.

Presidential Attacks on the Opposition

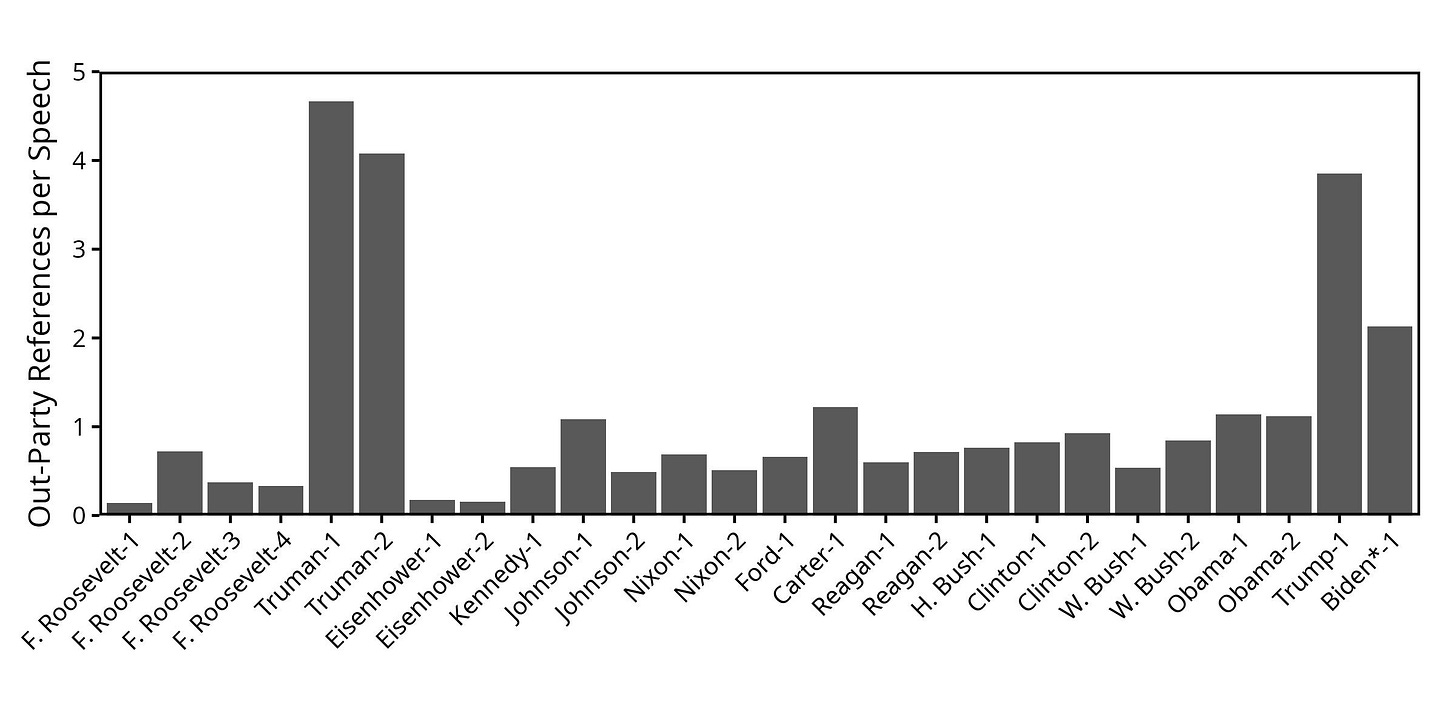

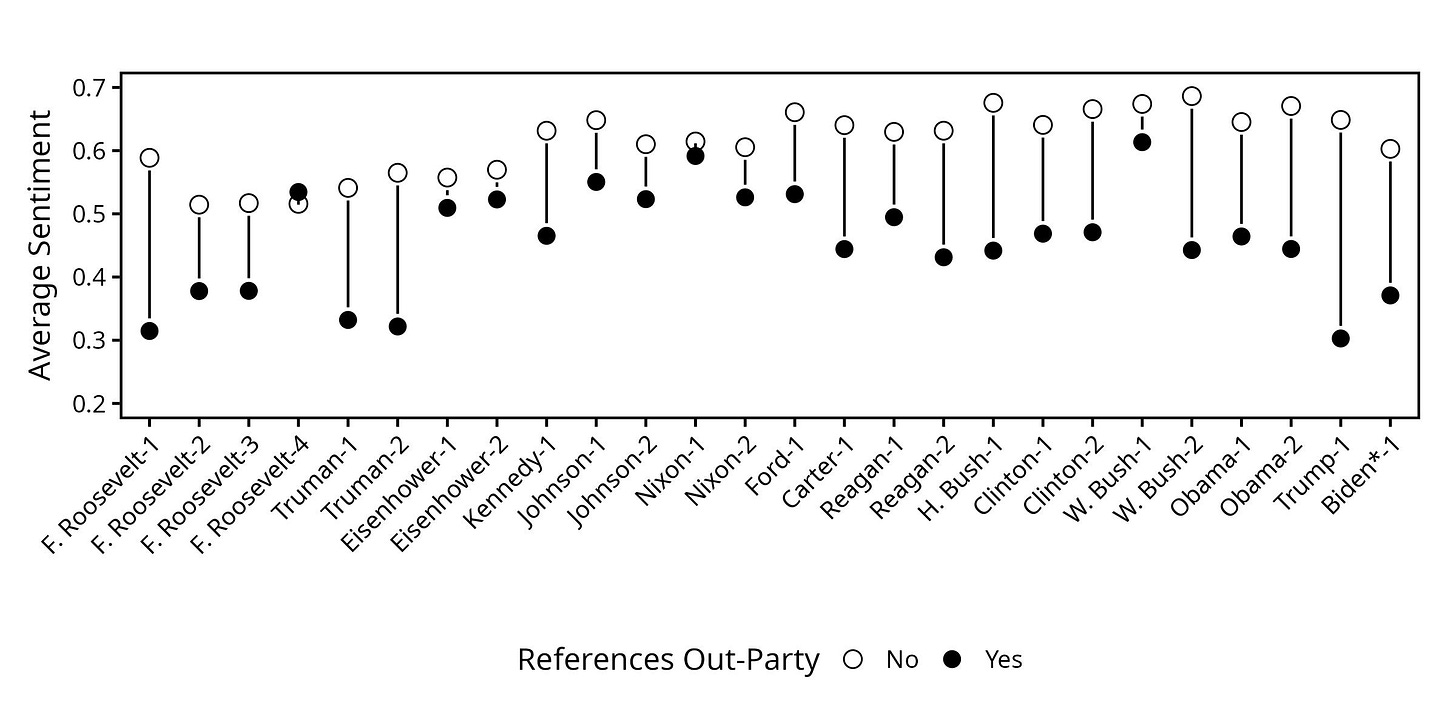

Presidents themselves participate in this dynamic, increasingly attacking the opposition party as polarization intensifies. Professor Noble’s analysis of presidential statements from 1933 to 2024 shows a marked increase in references to the opposition party, particularly in recent decades. These references aren't neutral—they've become increasingly negative over time.

When Congress is competitive or polarized, presidents increase both the frequency and negativity of their opposition-party references. This pattern appeared prominently during the Truman administration (a period of competitive and divided government) and has accelerated dramatically since the 1980s.

These presidential attacks effectively decrease their supporters' approval of the opposition party. By mobilizing negative partisanship among their base, presidents sacrifice short-term legislative cooperation for potential electoral advantages. The goal becomes winning future elections rather than finding common ground in the present.

The Symbolic Politics of Division

In a polarized environment, symbolic politics often displaces substantive policymaking. Politicians engage in performative opposition—highly visible actions designed to signal partisan commitment rather than achieve policy outcomes. Examples include:

Holding votes on messaging bills with no chance of passage.

Engaging in procedural obstruction to demonstrate opposition.

Using committee hearings for partisan questioning rather than information gathering.

These symbolic actions serve electoral purposes even when they fail to achieve policy goals. By demonstrating commitment to partisan priorities and opposition to the other side, politicians signal to their base that they're fighting the good fight, regardless of legislative outcomes.

Developments Alongside Political Polarization

As polarization has intensified in American politics, several important political and social trends have emerged concurrently. While causal relationships are difficult to establish definitively, understanding these parallel developments helps contextualize polarization's place in the broader political landscape.

Declining Trust in Government

One notable trend occurring alongside rising polarization has been declining public trust in government. Since the 1960s, the percentage of Americans who trust the government to do what is right most of the time has fallen from over 70% to under 20%. This decline in trust reflects numerous factors, including specific historical events like Watergate and Vietnam, economic challenges, and changes in media coverage of politics.

This trust deficit coincides with greater difficulty in addressing national challenges. When trust in institutions is low, citizens may be less willing to accept short-term sacrifices for long-term benefits, more skeptical of expert guidance, and more receptive to information that confirms their existing partisan predispositions.

Changes in Voter Engagement

The era of heightened polarization has coincided with shifting patterns in voter engagement. After decades of declining turnout from the 1960s through the 1990s, voter participation has increased significantly in recent elections, reaching its highest level since 1900 in the 2020 presidential election.

This increased participation has occurred during a period when the perceived stakes of elections have grown. As parties have become more ideologically distinct and political messaging has emphasized the risks of the opposition gaining power, voting may have taken on greater significance for many Americans. Survey research suggests that for many contemporary voters, negative feelings toward the opposing party provide a stronger motivating force than positive enthusiasm for their own party's candidates.

This engagement represents one positive development occurring alongside polarization—addressing the long-standing concern about low levels of citizen participation in American democracy.

Public Concern About Polarization

Americans themselves are increasingly concerned about polarization. A 2022 FiveThirtyEight/Ipsos poll found that "political extremism or polarization" ranked third among the most important issues facing the country, behind only inflation and crime/gun violence. Nearly 3 in 10 Americans (28 percent) named polarization as one of the country's most pressing problems.

The poll revealed an important insight about where Americans place responsibility for polarization. By a margin of 84 percent to 22 percent, respondents believed polarization is driven by "politicians and political leaders" rather than "people in your community." This suggests most citizens view polarization as something imposed from above rather than arising organically from public attitudes.

The poll also found that Americans overestimate how extreme the opposing party's views are. For example, while 64 percent of Republicans supported legal abortion in cases of rape, incest, or to save the mother's life, Democrats estimated that only 30 percent of Republicans held this position. These misperceptions contribute to polarization by making the parties seem more extreme and divided than they actually are on some issues.

Can Polarization Be Reduced?

Given polarization's deep roots in American politics, reducing its intensity presents significant challenges. However, research by political scientist James Fishkin and colleagues has found that deliberative conversation in mixed partisan groups can reduce negative partisanship by improving attitudes toward the opposing party. Their studies of "deliberative polling" bring together diverse citizens for extended discussion of policy issues with factual information and facilitated dialogue.

These deliberative experiences appear especially effective for those with the most extreme views, suggesting that meaningful cross-partisan engagement can moderate polarization under the right conditions.

Conclusion: Living with Polarization

Polarization represents one of the defining features of contemporary American politics. Its causes run deep in American society and political institutions, meaning quick or easy solutions are unlikely to succeed. Understanding polarization's strategic dimensions helps explain why it persists despite widespread public frustration with partisan conflict.

The strategic use of polarization creates a classic collective action problem. Individual politicians benefit from polarizing rhetoric and partisan appeals, but the political system as a whole suffers from reduced capacity to address shared challenges. Breaking this cycle requires changes in both institutional incentives and citizen expectations.

Perhaps most importantly, addressing polarization requires recognizing that rhetoric matters. How politicians talk about issues, opponents, and governance shapes not just short-term electoral outcomes but the long-term health of democratic institutions. When politicians routinely describe opponents as existential threats rather than legitimate competitors, these messages inevitably affect how citizens view both government and their fellow citizens.

Ultimately, reducing polarization's harmful effects requires a realistic assessment of both its causes and consequences. Rather than expecting a return to a perhaps mythical era of bipartisan cooperation, the path forward involves developing new norms and institutions that can function effectively even in a polarized environment. This might mean embracing conflict while finding ways to manage it productively—acknowledging partisan disagreements while maintaining basic shared commitments to democratic processes and outcomes.

Key Terms

Polarization: A political environment characterized by small within-party differences and large between-party differences.

NOMINATE scores: A method of measuring legislators' ideological positions based on their voting patterns.

Southern realignment: The shift of the American South from solid Democratic control to Republican dominance.

Insecure majorities: The condition of closely divided chambers of Congress where majority control is consistently at stake.

Negative partisanship: Political identity driven primarily by opposition to the other party rather than support for one's own.

Symbolic politics: Political actions designed primarily for their communicative value rather than their policy impact.