Learning Objectives

Understand the concept of democratic backsliding and how it differs from traditional coups.

Analyze the institutional and political factors that contribute to democratic erosion.

Evaluate how partisan competition and polarization can threaten democratic norms.

Examine the role of public attitudes and norms in enabling or preventing democratic backsliding.

Introduction: The Democracy Paradox

What if a majority in a democracy supports a policy that is undemocratic?

This seemingly paradoxical question strikes at the heart of one of contemporary politics' most pressing challenges. We often think of democracy as self-protecting—that democratic institutions and processes will naturally preserve themselves because citizens value democratic governance. Yet around the world, we're witnessing something troubling: democratically elected leaders systematically weakening the very institutions that brought them to power.

This phenomenon, known as democratic backsliding, represents a slow erosion of democratic institutions that makes it increasingly difficult to remove leaders through normal democratic means. Unlike the dramatic military coups that dominated headlines in previous decades, democratic backsliding operates through legal channels, making it harder to detect and resist. A leader doesn't seize power with tanks in the capital; instead, they gradually change voting rules, manipulate media access, and restructure institutions to advantage themselves and their supporters.

Consider recent global examples: In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has systematically restricted press freedom and manipulated election laws while maintaining the formal structures of democratic governance. In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has used constitutional changes and emergency powers to consolidate authority. Even in the United States, political scientists have documented concerning trends in states like Wisconsin and North Carolina, where extreme partisan gerrymandering has enabled legislative majorities to maintain power despite losing statewide popular votes.

What makes democratic backsliding particularly insidious is that it may enjoy popular support. Citizens may endorse policies that restrict voting access, limit press freedom, or concentrate power in executive hands—especially when these policies promise to advance their preferred outcomes. This creates a fundamental tension: Can democracy survive when democratic processes produce undemocratic results?

The Changing Nature of Democratic Breakdown

From Coups to Gradual Erosion

For much of the twentieth century, democracies died dramatically. Military officers stormed government buildings, arrested civilian leaders, and declared martial law. These coups were unmistakable—citizens woke up to find their government replaced overnight by military rule.

The frequency of such dramatic interventions has declined significantly since the end of the Cold War. Between 1990 and 2016, successful military coups became increasingly rare worldwide. When they do occur—as in Myanmar in 2021 or Egypt in 2013—they attract intense international condemnation and often trigger economic sanctions.

However, the decline in traditional coups doesn't mean democracy has become more secure. Instead, threats to democratic governance have become more subtle and harder to detect. Democratic backsliding represents this new form of democratic breakdown: the gradual weakening of democratic institutions by democratically elected leaders themselves.

In short, democratic backsliding is the process by which elected leaders systematically weaken democratic institutions, making it increasingly difficult for opposition forces to compete fairly or remove incumbents through normal democratic processes. Unlike coups, which violate democratic norms openly, backsliding operates within legal frameworks, making it appear legitimate while gradually eroding democratic competition.

How Backsliding Works

Democratic backsliding typically follows recognizable patterns. Leaders begin by targeting institutions that constrain their power or provide oversight of their actions.

Common tactics include:

Restricting Electoral Competition: Leaders may not eliminate elections entirely, but they can manipulate the rules to advantage themselves and their supporters. This might involve disqualifying opposition candidates on shaky legal theories or aggressively gerrymandering districts to create favorable electoral maps.

Controlling Information Flow: Rather than shutting down media outlets, leaders may limit government advertising to supportive outlets, restrict press access, or threaten critical journalists through violence or legal tactics.

Weaponizing Legal Systems: Courts and law enforcement agencies can be used to investigate political opponents while protecting allies from similar scrutiny. This creates the appearance of rule of law while selectively applying legal standards.

Limiting Civil Society: Organizations that monitor elections, advocate for policy changes, or organize political opposition may face intimidation or violence, restrictions on speech, and investigations.

Changing Constitutional Rules: Leaders may propose constitutional amendments that extend term limits, expand executive power, or pack the courts.

Each individual action might appear reasonable or even necessary. Voting procedures need updating, media regulation serves legitimate purposes, and constitutional reform can address genuine institutional problems. The cumulative effect, however, is to tilt the playing field in favor of incumbents while maintaining the formal appearance of democratic governance.

This gradual approach makes democratic backsliding particularly dangerous. Citizens may not recognize the threat until institutional changes have become entrenched and difficult to reverse. By the time opposition forces mobilize resistance, the tools they might use—courts, media, civil society organizations—may already be compromised.

The Roots of Democratic Backsliding

Why do democratic politicians engage in backsliding behaviors that undermine democratic governance?

Partisan Competition

When political competition becomes extremely intense, with control of government frequently alternating between parties, each side faces strong incentives to use institutional advantages to protect itself from future losses. Political parties may adopt institutional strategies to protect their interests that simultaneously threaten their opponents' ability to compete fairly.

Research by political scientists Kelsey Hinchcliffe and Frances Lee demonstrates this dynamic empirically. They found that states with more competitive partisan balance tend to exhibit higher levels of polarization in their legislatures. When control of government is genuinely up for grabs, parties stick together more cohesively and engage in more confrontational tactics.

The logic resembles dynamics we've seen in congressional polarization. When majority control is uncertain, parties have strong incentives to deny the governing party any successes that might help them in future elections. This "opposition at all costs" mentality can extend to institutional rules themselves. If changing voting procedures, redistricting, or expanding executive power might help secure future victories, the temptation to use these tools becomes overwhelming.

Contemporary American politics exhibits many characteristics that intensify this dilemma. National elections have become increasingly competitive, with control of the presidency and Congress alternating frequently between parties. State-level politics have similarly become more competitive as partisan identification has strengthened and ticket-splitting has declined. These conditions create environments where institutional manipulation appears necessary for political survival.

Polarization

Rising partisan polarization compounds the effects of competitive elections. When parties move farther apart ideologically, the policy consequences of electoral victories and defeats become more significant. This raises the stakes of political competition and makes leaders more willing to bend institutional rules to prevent their opponents from taking power.

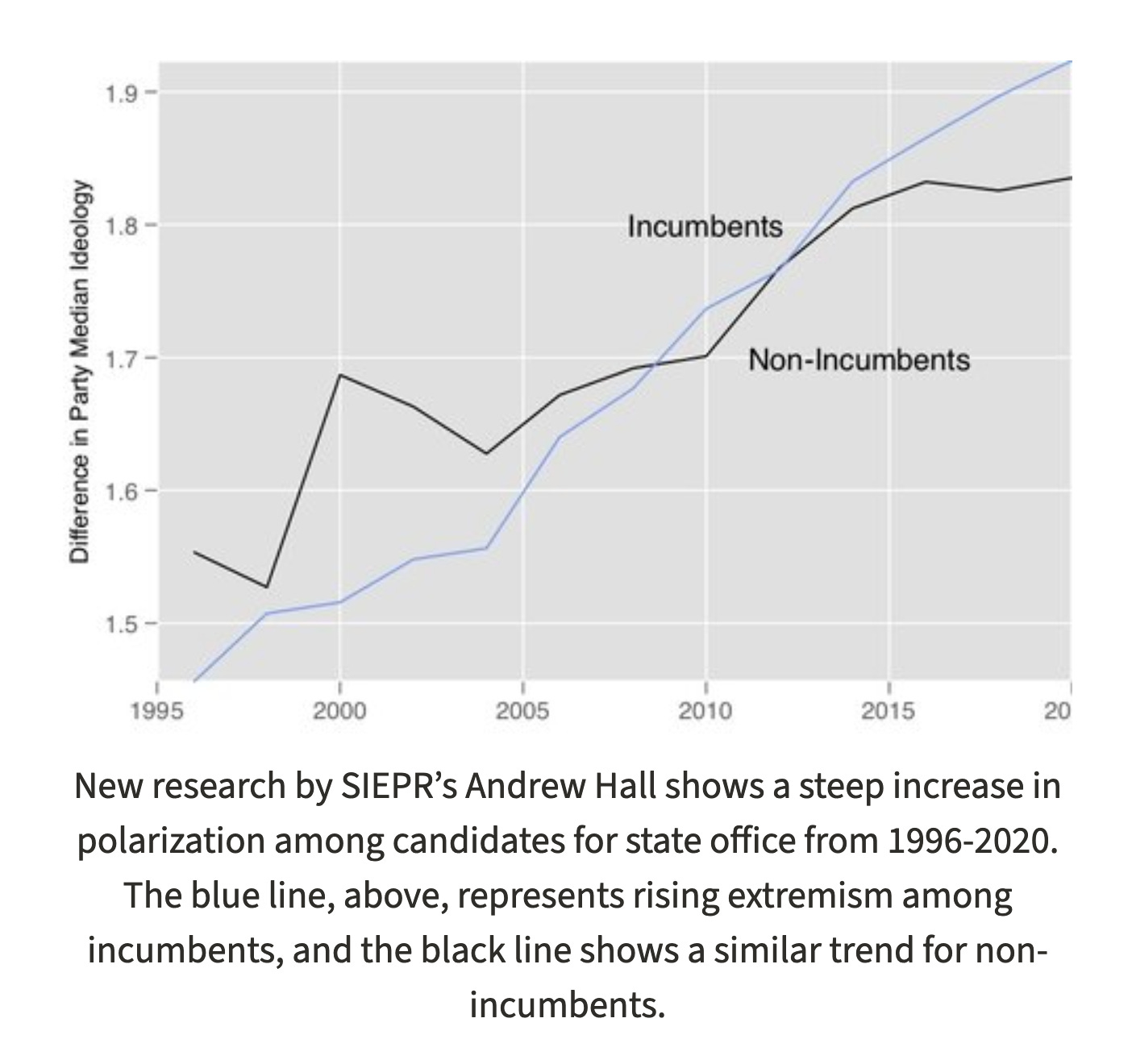

Political scientist Andrew Hall's research documents this trend at the state level, showing that the ideological distance between candidates for state office has increased substantially since the 1990s. As parties have become more ideologically distinct, the policy differences between Republican and Democratic governance have become more pronounced.

Higher stakes create stronger incentives for institutional manipulation. If allowing the opposition party to win elections means accepting policy outcomes that party members view as disastrous, then preventing opposition victories through institutional means becomes more attractive. This logic can justify increasingly aggressive tactics: if the other side represents an existential threat to important values, then extraordinary measures to stop them may seem necessary.

Polarization also affects how citizens evaluate political behavior. When people view the opposing party as fundamentally dangerous or illegitimate, they become more willing to support their own party's norm-breaking behavior. If the other side represents a threat to democracy, civil rights, economic prosperity, or moral values, then perhaps it's acceptable for "our side" to bend the rules to keep them out of power.

Negative Partisanship and Democratic Legitimacy

Contemporary American politics exhibits what political scientists call negative partisanship—party identification driven more by dislike of the opposing party than positive feelings toward one's own party. Survey data from the American National Election Studies shows that since the 1980s, Americans' feelings toward the opposing party have become increasingly negative, while feelings toward their own party have remained relatively stable or even declined slightly.

This pattern suggests that many Americans are motivated more by opposition to the other party than by enthusiasm for their own party's agenda. If large numbers of citizens view the opposing party as fundamentally illegitimate rather than simply wrong on policy, the shared commitment to democratic processes that enables peaceful transfers of power begins to erode. A recent study by Campos and Federico shows that negative partisanship is associated with “greater support for elite actions that dismantle democracy, less support for democratic norms, and more support for political violence.”

Public Attitudes and Democratic Backsliding

When Partisan Loyalty Collides with Democratic Norms

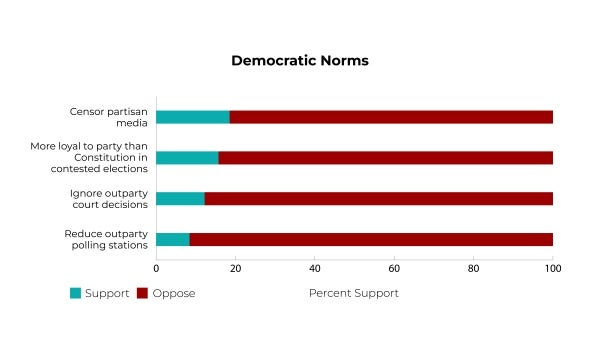

Most Americans still endorse democracy in the abstract—large majorities rate free elections and a free press as “essential.” Yet a consistent minority wavers when partisan stakes are explicit. In a series of experiments, Matthew Graham and Milan Svolik asked voters to choose between hypothetical candidates who varied both in policy positions and in respect for democratic rules (e.g., willingness to gerrymander aggressively or restrict protests). Strong partisans often selected the co‑partisan who threatened democratic norms over an opponent who promised to uphold them, confirming that some citizens will trade procedural safeguards for policy wins.

Subsequent work complicates the picture. Studies that screen out inattentive respondents or embed more detailed vignettes find that unconditional support for outright democratic violations remains low. However, there is some willingness among a minority to endorse norm‑breaking in both parties.

Taken together, evidence indicates that partisan incentives can erode one’s commitment to democracy, but the phenomenon is concentrated among highly polarized voters and is sensitive to how researchers frame the choice. The challenge, then, is less a wholesale rejection of democracy and more the danger that a committed minority—activated by elite cues—can tip the balance when institutions are already fragile.

The Limits of Democratic Self-Protection

These patterns challenge a fundamental assumption about democratic governance: that democracy is self-protecting because citizens value democratic processes. If a substantial minority is willing to support undemocratic policies when those policies benefit their side, then democratic institutions cannot always rely on popular resistance to protect themselves from erosion.

This creates a paradox: Democratic processes may produce outcomes that undermine democracy itself. When majorities support restrictions on minority rights, limitations on free speech, or manipulation of electoral rules, democratic institutions face an impossible choice between respecting majority will and preserving democratic competition.

The implications extend beyond individual policy decisions. If citizens evaluate political behavior primarily through partisan lenses rather than democratic principles, then politicians face fewer electoral costs for engaging in norm-breaking behavior. Indeed, they may face electoral rewards for institutional manipulation that advantages their supporters.

This suggests that formal constitutional protections may be insufficient to preserve democratic governance. Constitutions are, ultimately, just pieces of paper. Their effectiveness depends on political actors' willingness to respect constitutional constraints and citizens' demands that their leaders operate within constitutional boundaries. When these informal supports weaken, formal protections may prove inadequate.

Solutions and Safeguards

Given that politicians and the public may not limit democratic backsliding, what are potential solutions or safeguards?

Institutional Reforms and Their Limitations

Various institutional reforms might help address democratic backsliding, but each faces significant limitations:

Redistricting Reform: Independent redistricting commissions or mathematical standards for district drawing could reduce partisan gerrymandering. However, these reforms often require approval from the same legislators who benefit from current arrangements.

Voting Access: Expanding voting access through measures like automatic registration, extended early voting, or vote-by-mail could reduce opportunities for electoral manipulation. But these changes also require approval from political actors who may benefit from more restrictive rules.

Media Regulation: Although some are concerned about misinformation and partisan media, efforts to alter the media landscape raise legitimate concerns about government control over information and free speech. After all, who gets to determine what constitutes “misinformation?”

These challenges lead us to the importance of democratic norms: institutional reforms may help, but they cannot substitute for political leaders' voluntary restraint in using their institutional advantages.

The Role of Democratic Norms

Political scientists Levitsky and Ziblatt argue that preventing democratic backsliding requires maintaining two crucial democratic norms: mutual toleration and forbearance.

Mutual toleration means recognizing political opponents as legitimate participants in democratic competition. Even when we disagree strongly with the opposing party's policies or leadership, we acknowledge their right to compete for power and their legitimacy when they win elections. This norm enables peaceful transfers of power and prevents winners from using their temporary advantages to permanently exclude losers from competition. Although people may say someone is “not my president,” this represents a lack of mutual toleration. Mutual toleration requires an acknowledgement that even if you don’t support the winner, they have the right and authority to govern.

Forbearance means exercising restraint in using all of your powers, even when the Constitution permits more aggressive action. Politicians may have the legal authority to pack courts, eliminate opposition offices, or manipulate electoral rules, but forbearance requires them to refrain from using these powers in ways that undermine democratic competition. For example, it was permissible for Senate Majority Leader McConnell to deny President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee a Senate confirmation hearing. However, this represented a lack of forbearance. McConnell pushed his authority to limit rather than stick within the spirit of the rules.

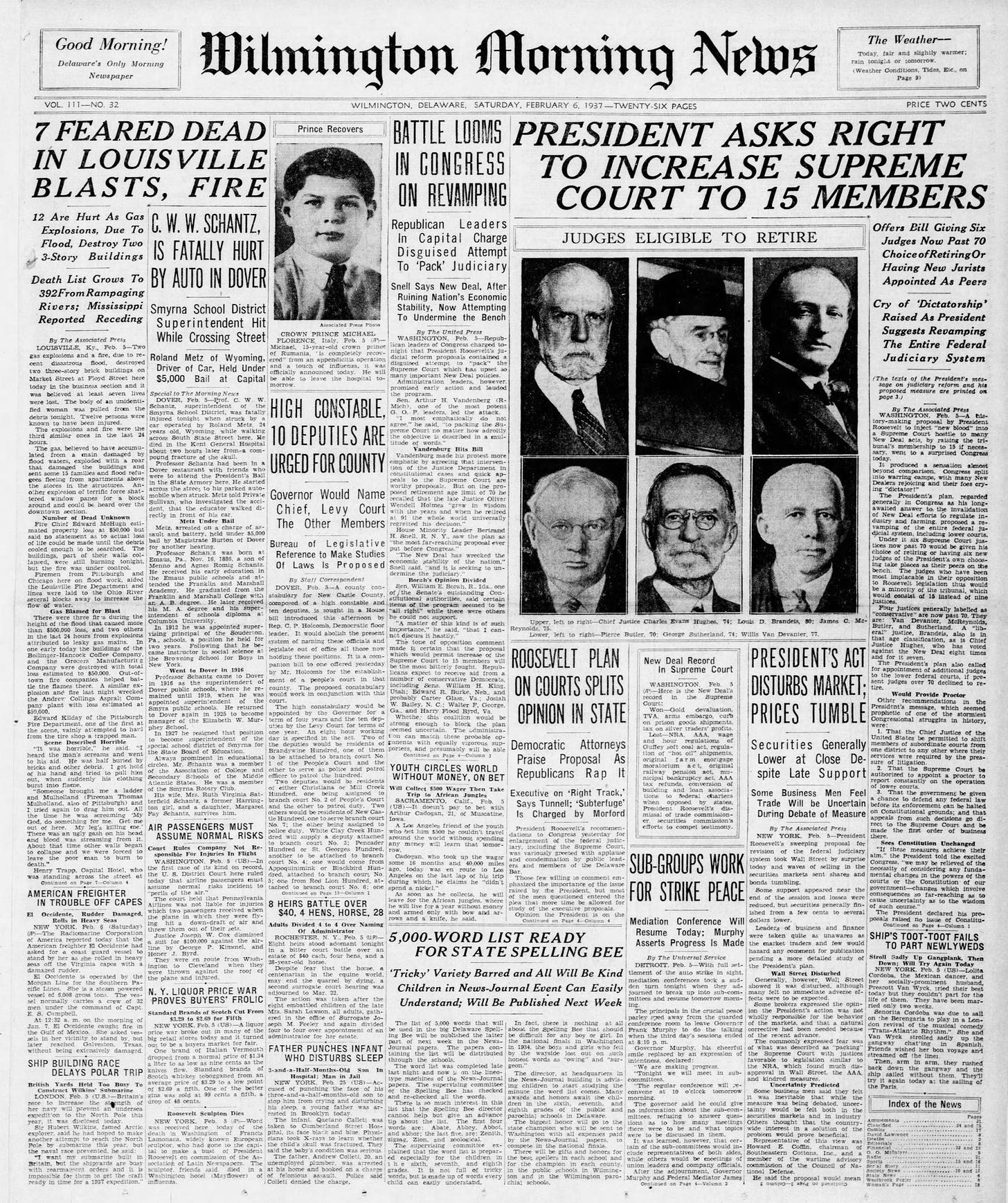

These norms have historically constrained American political behavior in important ways. Presidents could pack the Supreme Court by expanding its size, but they haven't done so since Franklin Roosevelt's failed attempt in the 1930s. Senators could block all opposition presidential appointments, but this was rare until recent decades. State legislatures could gerrymander districts more aggressively, but traditional practices limited the most extreme manipulations.

The erosion of these norms creates a spiral dynamic. When one side breaks a norm, the other side feels justified in responding with similar behavior. Neither side wants to unilaterally disarm by following norms that their opponents ignore. This tit-for-tat escalation can quickly undermine institutional constraints that took decades to develop.

The Federal Structure as Protection and Vulnerability

America's federal system creates both opportunities for democratic backsliding and mechanisms for resistance. On one hand, federalism enables state-level democratic erosion even when federal institutions remain competitive. Gerrymandering, voting restrictions in various states, and efforts to manipulate election administration all demonstrate how state governments can undermine democratic competition within their jurisdictions.

On the other hand, federalism also provides multiple venues for democratic resistance. When one level of government engages in backsliding, other levels may provide checks. Federal courts can overturn state laws that violate constitutional principles. State governments can resist federal overreach through their control of election administration and policy implementation. Local governments can pursue different approaches when state or federal policies prove inadequate.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Challenge

Democratic backsliding represents one of the most serious challenges facing contemporary American politics. Unlike the dramatic coups that characterized earlier threats to democracy, backsliding operates through legal channels that make it difficult to detect and resist. By the time citizens recognize the threat, institutional changes may already be entrenched and difficult to reverse.

The American federal system creates particular vulnerabilities to democratic backsliding. State governments possess significant authority over electoral rules, legislative representation, and policy implementation. When state-level competition becomes intense and norms of forbearance erode, opportunities for institutional manipulation multiply.

Perhaps most concerning, democratic backsliding sometimes enjoys popular support. When citizens prioritize partisan victory over democratic processes, they may endorse policies that undermine fair competition. This challenges fundamental assumptions about democracy's self-protecting nature and suggests that formal constitutional protections may be insufficient without supporting norms and attitudes.

The path dependence we've seen throughout American political development applies here as well. Current institutional arrangements reflect historical compromises and power relationships. Once parties entrench institutional advantages through gerrymandering, voting restrictions, or other manipulations, changing these arrangements becomes extremely difficult. Those who benefit from current rules have little incentive to make competition more fair, while those harmed by current rules often lack the power to force changes. Yet there are reasons for cautious optimism. When citizens mobilize effectively institutional changes are possible.

Ultimately, preventing democratic backsliding requires both institutional safeguards and commitment to democratic norms from political leaders and citizens alike. Formal rules matter, but their effectiveness depends on informal practices of mutual toleration and forbearance. When these norms erode, formal protections may prove inadequate. When they remain strong, even flawed institutions can sustain democratic competition.

The challenge for contemporary American democracy is maintaining these norms in an era of intense partisan competition and ideological polarization. As the stakes of political competition increase and party loyalties strengthen, the temptations to bend institutional rules become more powerful. Whether American democracy can resist these pressures while addressing legitimate concerns about representation and governance remains an open question—one that will be answered through the choices made by political leaders and citizens in the years ahead.

Key Terms

Democratic backsliding: The gradual erosion of democratic institutions and norms by elected leaders, making it increasingly difficult to remove them through normal democratic processes.

Mutual toleration: The democratic norm of recognizing political opponents as legitimate participants in democratic competition.

Forbearance: The democratic norm of exercising restraint in using institutional powers, even when such use is legally permissible.

Negative partisanship: Party identification driven primarily by dislike of the opposing party rather than positive feelings toward one's own party.